Book review: Judicial Uses of Images by Peter Goodrich

We review a scholarly investigation of the use of various kinds of image in judicial decision making… Continue reading

Subtitled “Vision in decision”, Professor Goodrich’s study of the Judicial Uses of Images sets out to catalogue, analyse, and review “the normative significance and affective force” of the “increasing use of images in precedent in the common law world”. The book is nothing if not thorough, but the writing is so densely academic that I suspect most non-academic readers will find it pretty tough going.

Stepping back a bit, for the benefit of the lay reader, think of it like this. It’s often said that “a picture is worth a thousand words”. But the law is usually expressed in words. People speak of “black letter law” as meaning a clear set of rules, unambiguously expressed in prose, leaving no room for doubt. (An aspiration, not always matched in practice.) What happens if you try to express or explain the law using pictures or other kinds of image, such as maps, diagrams, symbols, icons, or emoji? Does it replace the words that you might have used, does it enhance them, or does it distract from them? That, I think, is the main point of the learned professor’s inquiry.

The book is focused on the judicial use of images, as the title indicates, meaning their use in giving judgment in various types of litigation. It is not concerned with the use of images to explain the law outside the judicial context, as a teaching aid, for example, or as an aspect of legal design. (For more on this, see Design in legal education, edited by Emily Allbon and Amanda Perry-Kessaris, reviewed here.)

Image as precedent

Goodrich is interested in the precedential value of the image incorporated in a court’s judgment. In a common law system, should (and, if so, how does) the image form part of the ratio decidendi that binds a later decision-maker under the common law doctrine of precedent?

This seems to me a valid inquiry, although perhaps of limited consequence. My initial assumption would be that in the vast majority of cases where images appear in a judgment they will have been included only as part of the factual matrix, the circumstances in which a question of law arises for decision, and that the answer to that question could always be expressed in words. A case involving a boundary dispute might include a map or plan; a case involving a collision at sea might include a chart or diagram; a dispute over trade marks might include the marks in dispute; a case about designs might show the designs in question; and a copyright case might show disputed images or music notation. But it would be unusual for them to form part of the ratio, such as to necessitate their reproduction in any later judgment following, applying or distinguishing the earlier decision. This may be why, as Goodrich points out, such images are often not even retained in the published report of the decision.

He complains, by way of example, about how the decision of the Supreme Court in PMS International v Magmatic [2016] UKSC 12 has been published, with images being omitted from what he calls the “official BAILII report” and the court-ready online report on LEXIS reproducing them only in black and white, despite colour being a key component in the analysis of the dispute (in which the parties locked horns over suitcase designs). I’m glad to see that the ICLR report in the Business Law Reports did include what Goodrich calls the “ocular dimension” of the record, albeit in monochrome: see [2016] Bus LR 371. (NB it looks better if you download the PDF.)

While in most such cases the images merely illustrate or help us to understand the legal ruling, what happens if an image forms an essential part of the ruling? What it the ruling makes no sense without the image that, in whole or in part, records and expresses it? Or to look at it from an ICLR perspective, what if the image would have to be included in the headnote?

I would like to say that I’d read the whole book and found, or not found, particular images among the many examples given that did have that essential quality. (The ones I did see, like the case about the suitcases, did not.) But unfortunately I found the book too heavy going to persist with more than a couple of chapters, for which I feel unworthy. The problem was sentences like this:

“Retinal justice references a pre-reflective visual apprehension that mobilizes a shadow archive of images, a preconscious relay of emblematic effects, archetypes, and adumbrations of persons, things, and actions that structure and constitute both sociality and positive law.”

Winking or smiling?

Another problem I had was that one of the examples given happens to be a case with which I am extremely familiar, having written a blog post about it and having later discussed it in a book of my own. As an example of what he calls “retinal justice”, Goodrich cites “an English child custody case in which the judge inserted an emoji several times in the judgment”. The emoji was of a smiling face, which the police had claimed was winking, but the judge said it was not winking, it was only smiling. In Lancashire County Council v M [2016] EWFC 9 , 27(11) it appears thus:

“I don’t agree that the ☺ is winking. It is just a ☺.”

According to Goodrich,

“The Honourable Mr Justice Peter Jackson reproduces unwinking smiley faces but misses the point that on screen emojis act quite differently to emojis in word documents and that without knowing the algorithmic source of the emoji or the platform and program of its delivery onscreen it is impossible to state with certainty what form, appearance, dance, or sign it will make.”

But in my view it is Goodrich who misses the point. These emojis are in the judgment because it was written in a deliberately clear and simple way so that the children concerned would be able to read and understand it. The emojis are quoted from a note which the mother left in a caravan for the father’s sister. A note left in a caravan doesn’t sound like something the nature of which might change according to the software used to write or read it. The judgment later refers to WhatsApp messages which would be digital. It seems to me obvious that the message in the caravan was scribbled on paper and the dispute over whether it was winking or smiling arose from the nature of the marks on the paper, not the software used to describe or reproduce it in the judgment.

That doesn’t detract from Goodrich’s point about the malleability of software-dependent images (the above quoted emojis may look different on different browsers, for example), and he goes on to discuss a case on whether a string of emojis, while not amounting to written acceptance of a contract, could nevertheless give rise to a promissory estoppel in the context of a contract for the lease of an apartment. A fascinating point, no doubt, but not one in which failing to reproduce the emojis would render the precedent (if there was one) non-binding.

Partly covered

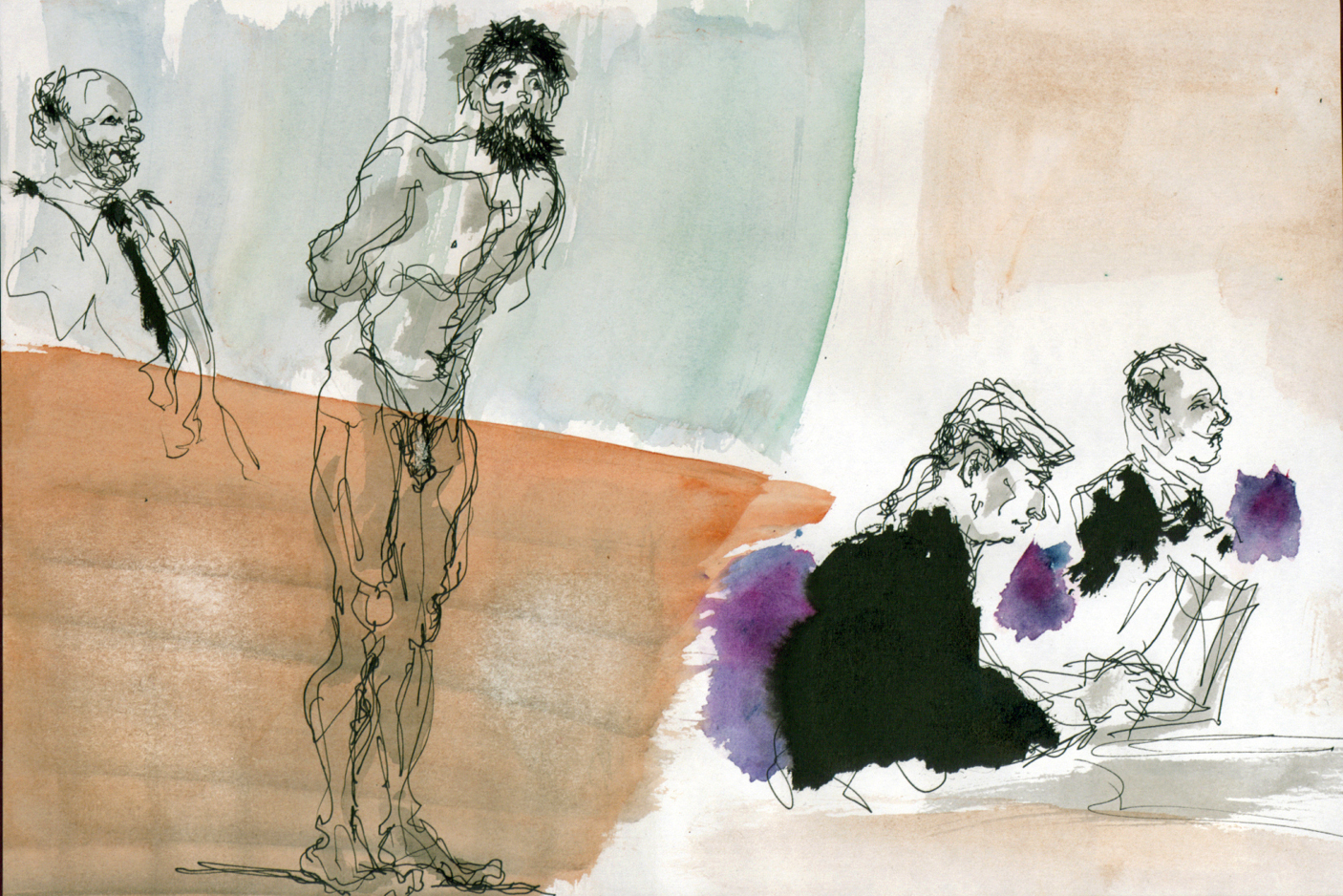

Finally I must comment on the book’s cover, which reproduces a sadly incomplete image of the so-called Naked Rambler, Stephen Gough, drawn by Isobel Williams after a hearing (and, for those there, a seeing) in Winchester Crown Court for her blog, Drawing from an Uncomfortable Position:

It’s a great picture, but it isn’t a judicial image or one used or referred to by a judge in a judgment, so technically irrelevant. But then quite a lot of the images inserted into judgments seem, on Goodrich’s analysis, to be largely irrelevant, whether they are inflatable rats, or crosses, or pictures of ostriches which their heads in the sand. Sometimes judges just put them in for their own amusement, it seems, or to humiliate counsel, or for no better reason than that they can. Collecting them all must have been a lot of fun. One day I may get round to reading about the rest of them.

Judicial Uses of Images by Peter Goodrich (Oxford, £78)

Featured image (top): we’ve used artificial intelligence (via Shutterstock) to create a collage or mashup of all the different types of image that might be incorporated in a judgment. It is, if you like, a hallucination of the subject of the book.