Book review: Design in legal education, edited by Emily Allbon and Amanda Perry-Kessaris

Paul Magrath reviews a pivotal collection of essays and observations about the use of designerly thinking in legal education … Continue reading

Legal design is a consideration of the medium through which we present and discuss legal ideas. Typically, that will be through speech and text. But it needn’t be. There are other ways of presenting or conveying the ideas.

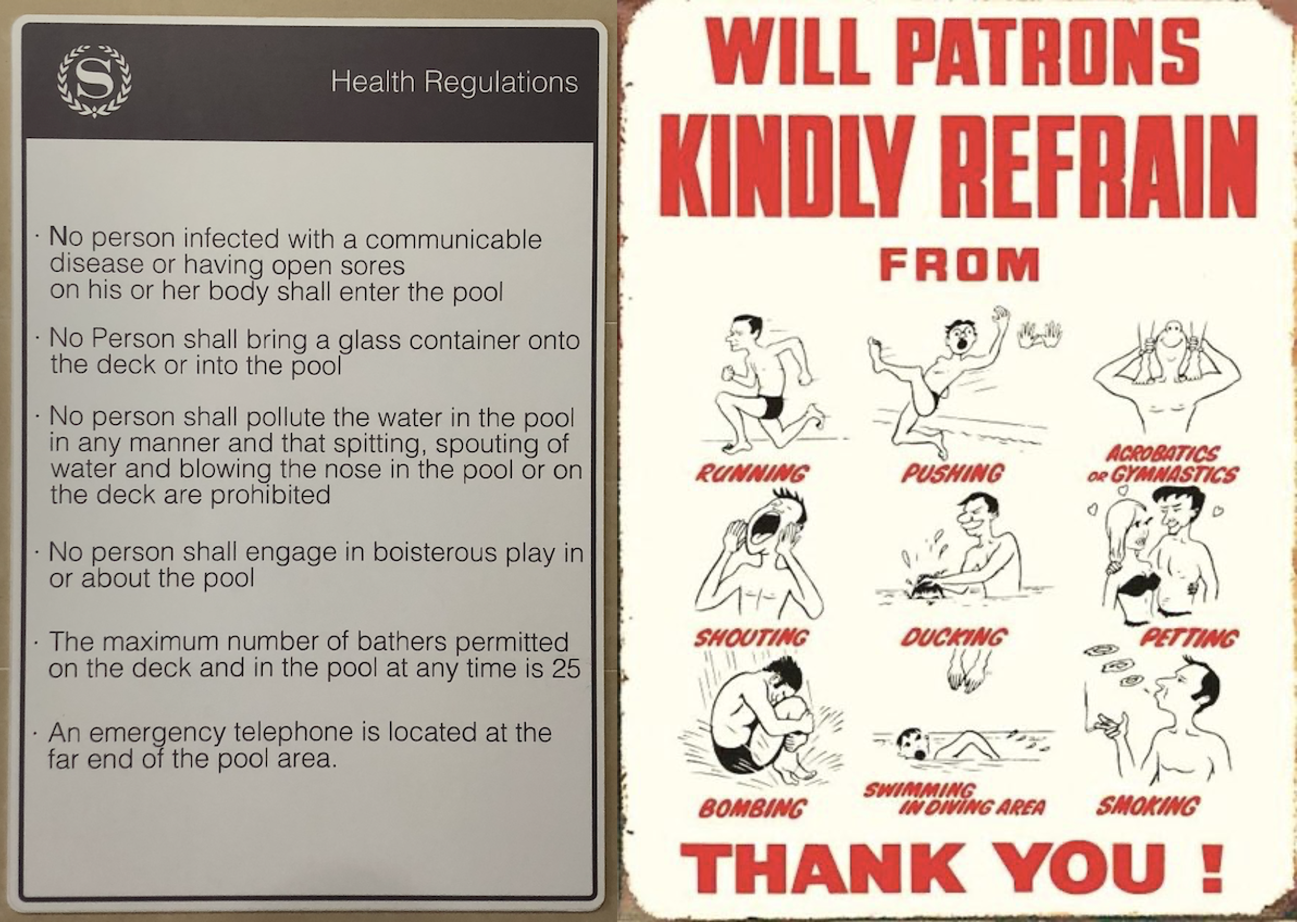

Compare, for example, these two different ways of publicising the rules of conduct in a public swimming pool:

The images, though dated, are in many ways far more effective. Whether they would stand up to judicial scrutiny in the event of a dispute is another matter.

There are other ways of making rules or contract terms more intelligible to those who lack the linguistic skill to consume them in purely verbal form. Everyone is now familiar with the use of icons and emojis to simplify and illustrate digital messages and instructions. And the use of imagery to convey power or status is as old as sealing wax and ceremonial costumes. Words alone are not enough to signify the status and roles of law givers and enforcers. We need wigs and gowns and (in some jurisdictions) gavels to reinforce the grand names and spoken words. Like religion and the military, law is a world of signs and designs.

For the teaching and study of law, design thinking offers a range of channels of engagement. This book explores what design can do for legal education. According to its editors, Emily Allbon (Associate Professor of Law at City Law School) and Amanda Perry-Kessaris ( Professor of Law at Kent Law School) “design” in this context can be defined

“broadly to include a wide range of practices that are devoted to the planning and making by humans of tangibles and intangibles including, for example, product design, graphic design, system design and interaction design”.

As their various contributors in their different chapters attest, design can help make complex ideas accessible and digestible; it can encourage students to engage with ideas and foster collaboration between different disciplines; it can lead to better teamwork; and can make what students learn more memorable and teach them how better to communicate advice to their future clients. At its most basic, it can help overcome the eternal “because we’ve always done it that way”.

The book’s contributors offer a variety of different approaches, including labs, workshops, mock trials, diagrams, cartoons, and even models made of LEGO (about which more anon). One of the projects described involved building a smartphone app. While some are concerned with the education of students, others are more focused on public legal education and the use of design to help make the legal system more transparent. As Emily MacLoud in her chapter on Designing access to the law, says:

“Visuals can be used to help law students understand complex legal concepts, enable citizens to navigate legal information and even make a lawyer’s work more satisfying”.

If you think about it, a court trial is an intensively designed experience, much of it visual. Quite apart from the wigs and gowns, and coats of arms, there is also the way the participants are physically arranged, with the elevated judge on the “bench”, and the way the proceedings are staged according to a well-established script. This has become more apparent now that so many hearings are conducted on video screens, making them even more of a pictorial experience, despite the century-old statutory prohibition against drawing or photography in court — a point well explained by Isobel Williams in Judging by appearances, her chapter about court artists, the Supreme Court, and the Naked Rambler. (Yes nudity is a kind of design, too. A stripped down version.)

Design is not always benign; it can also, as Hallie Jay Pope reminds us, be used to perpetuate oppressive power structures. (Pope is founder of the Graphic Advocacy Project.) Moreover, while design can help make things more accessible, for example by presenting them online, there is also the risk of inadvertently excluding those who lack the necessary digital skills – a concept known as “digital exclusion”.

The book is thought provoking and useful, not just for educators, but for anyone involved in the design of information. My own concern, for example, is website design and the presentation of legal information and tools to help people find it. I found much here that was relevant to those concerns. But I was a bit disappointed at how poorly designed the book itself was, as a book about design. Not the authors’ fault, I fear, but an unwillingness by the publishers to give the text the setting and illustrations it deserved. There are illustrations and diagrams, but the quality of reproduction is poor. Given the price of the book, in hardback, a glossier publication might well have been justified. But don’t let that detract from its usefulness. I would still recommend it highly.

Launch event: a playful approach

To mark the launch of this book last November, the editors staged a day of hands-on activities at City Law School, Experimenting with design in legal education, in which visitors were encouraged to “Build a prototype, get user-centred, visualise a concept, simplify a bit of legalese, communicate a process”. There were quizzes and quests, cartoons and collaborations, questionnaires and games and discussions with some of the contributors and teachers. It was thought provoking and above all fun.

Many of those attending were not lawyers, so I took the opportunity of a construction toy (LEGO) to visualise and explain one of my favourite cases, thus:

Can you tell which case it was? It’s one of the three most famous cases known to all former law students but no smokeballs or snails in ginger beer were involved. Necessity is not a defence to murder, the court held, and will not excuse cannibalism on the high seas.

Fun fact: the fictional tiger in The Life of PI, Richard Parker, was named after the cabin boy victim in the case of R v Dudley & Stephens 14 QBD 273. (There, I’ve let the big cat out of the bag.)

You can find out more about the book here: Design in Legal Education, edited by Emily Allbon and Amanda Perry-Kessaris (Routledge, £130 HB, £35.09 EB)