Case Law On Trial – the results: 1971-1995

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period.… Continue reading

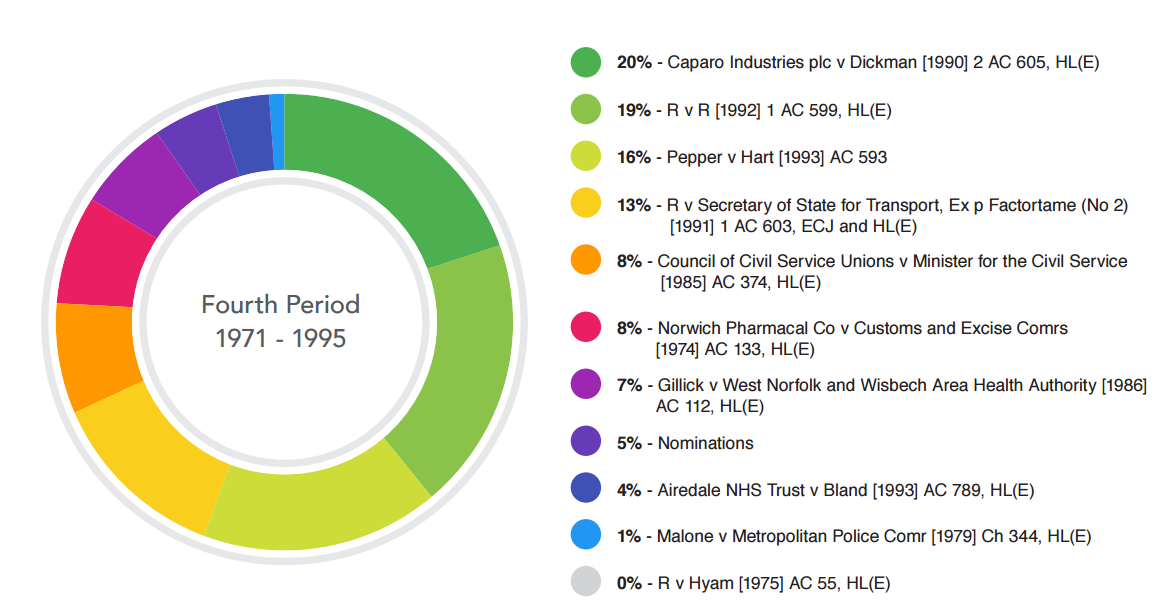

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period. In this post, we look at the results from the fourth period, 1971-1995.

The vote for this period was rather closer than previously, with the top three cases all arriving at the finishing line in quick succession. There were some other strong contenders, as the above list shows. In this post we take a closer look at the three that made the grade and assess their significance.

Caparo Industries plc v Dickman [1990] 2 AC 605, HL(E)

At first blush the headnote suggests this case is concerned with the question whether auditors of a company’s accounts might owe a duty of care to those, whether shareholders or otherwise, contemplating investing in the company. But its true significance goes much wider than that. After a period of uncertainty as to the correct test to be applied in determining whether, for the purposes of a claim in negligence, a duty of care existed, Caparo laid down a new, three-part test which was designed to settle that question once and for all.

The essential passage is in the speech of Lord Bridge of Harwich, at pp 617-619, (with numbering inserted):

“What emerges is that, in addition to [1] the foreseeability of damage, necessary ingredients in any situation giving rise to a duty of care are [2] that there should exist between the party owing the duty and the party to whom it is owed a relationship characterised by the law as one of “proximity” or “neighbourhood” and [3] that the situation should be one in which the court considers it fair, just and reasonable that the law should impose a duty of a given scope upon the one party for the benefit of the other.”

The speeches of their Lordships, particularly that of Lord Bridge, seem conscious of the fact that they were attempting to resolve a difficulty with which the courts had been grappling for some time. Lord Bridge notes, at p 616, that

“In determining the existence and scope of the duty of care which one person may owe to another in the infinitely varied circumstances of human relationships there has for long been a tension between two different approaches.”

This was what their Lordships intended to resolve. As John Randall QC explains in his helpful commentary on the case ( “Legal Celebrity or Jurisprudential Substance: Caparo v Dickman”, in McDougall, Cases That Changed Our Lives (2010), p 139, 144),

“these were speeches which were, from the start, consciously intended to set the law on a new path, and to reduce for the future the significance of a speech which had stood for almost 60 years as the definitive statement of the ‘general principle’ theory of the modern law of negligence, that of Lord Atkin in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562, 580.”

That “general principle” theory introduced by Lord Atkin had marked a move away from the traditional “incremental” approach whereby novel categories of negligence were examined and added only by analogy to existing categories. Now, it seems, the pendulum was swinging back, perhaps in retreat from an over-expansion in the categories of negligence to which the development of the general principle had given rise.

“All this was in marked contrast”, writes Randall, “to the confident assertion of Lord Wilberforce”, in Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1978] AC 728, 751 that:

“Through the trilogy of cases in this House – Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562, Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465, and Dorset Yacht Co Ltd v Home Office [1970] AC 1004, the position has now been reached that in order to establish that a duty of care arises in a particular situation, it is not necessary to bring the facts of that situation within those of previous situations in which a duty of care has been held to exist.”

The two-stage general test which had by then been developed (and which Lord Wilberforce then set out, at pp 751-752) involved asking, first, whether there was between the parties a sufficient relationship of proximity or neighbourhood such as that, in the reasonable contemplation of the alleged wrongdoer, carelessness on his part might be likely to cause damage to the other. If so, a prima facie duty of care arose, and it then became necessary to ask whether (as a matter of policy) there were any considerations that ought to negative or reduce or limit the scope of the duty or the class of persons to whom it was owed or the damages to which a breach of it might give rise.

The difference between that and the threefold test famously laid down in Caparo is, according to Randall (pp 145-146) that

“Lord Wilberforce’s first area of inquiry equated foreseeability of damage with a sufficient relationship of proximity or neighbourhood between the parties … whereas the three-fold test separated them out into cumulative requirements.”

Moreover, Lord Wilberforce’s test allowed the establishment of a prima facie duty before considering whether it should be negatived by any policy considerations, whereas the three-fold test in Caparo required all three limbs of the test to be satisfied before any duty could arise.

R v R [1992] 1 AC 599, HL(E)

This case, which for disambiguation is sometimes indexed as R v R (Rape: Marital Exemption), effected a major change in the criminal law relating to rape, by abolishing the existing presumption that a wife was deemed to have consented irrevocably to sexual intercourse with her husband. If lack of consent were proved, a husband could henceforth be convicted of the rape of his wife.

The case is regarded as a high water mark of judicial activism, effectively an example of judge-made legislation, because it didn’t merely “discover” the common law as it must be supposed to be, or clarify it in some way to enable it to be applied to new circumstances; but, by declaring that it “no longer applied”, effectively repealed an existing common law rule and created a new one in its place. The fact that Parliament could at any time have legislated to the same effect and failed to do so may have justified this development, but does not prevent its being, in a sense, a dangerous precedent.

The source of the common law “immunity”, as it’s sometimes put (see, for example, PGA v The Queen [2012] HCA 21; 245 CLR 355 ) – though to use such a term involves a recognition that there is still an underlying offence – is the pronouncement of Sir Matthew Hale in his History of the Pleas of the Crown (1736), vol 1, ch 58, p 629:

“But the husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this kind unto her husband which she cannot retract.”

The proposition had not gone unchallenged, as will appear from the judgment of the court given by Lord Lane CJ in the Court of Appeal (also included in the combined report from the Appeal Cases which follows, at pp 603ff). Even in Victorian times it was being questioned (see the judgments of Wills and Field JJ in R v Clarence (1888) 22 QBD 23, 33, 57). By the late 20th century the idea that a wife or her body was but the chattel of her husband, to do with as he wished, and that the marital contract, with its implied term of permanent consent to the conjugal act, however performed, should somehow take precedence over the criminal law of England must have seemed more than repulsively quaint.

Though he puts it more elegantly, this is in essence what Lord Keith of Kinkel is saying at p 616 in this report:

“Hale’s proposition involves that by marriage a wife gives her irrevocable consent to sexual intercourse with her husband under all circumstances and irrespective of the state of her health or how she happens to be feeling at the time. In modern times any reasonable person must regard that conception as quite unacceptable.”

Though the decision in R v R appeared to follow the prevailing wind of change – as the report notes, the House considered and applied the recent similar decision of the High Court of Justiciary in Scotland in S v HM Advocate, 1989 SLT 469 – it was by no means a foregone conclusion. An interesting comparison may be made with the Australian case, already cited, of PGA v The Queen 245 CLR 355, and in particular the dissenting judgments of Heydon and Bell JJ. The case concerned the continued effect of the common law rule expressed by Hale as it applied (or didn’t) in the state of South Australia – albeit the offence to which the case related was an historic one alleged to have occurred in 1963. The majority of the High Court of Australia found a way of cutting the Gordian knot which, for all his detailed erudition, seems to have eluded Heydon J and his fellow dissenter, Bell J. But the fact that there were dissenters at all is remarkable, and perhaps only justified by the historic nature of the allegation and the alarmingly retrospective nature of the rule proposed. (For more on this case, see Lesses, “PGA v the Queen: Marital rape in Australia: the role of repetition, reputation and fiction in the common law” (2014) 37(3) Melbourne University Law Review 786.)

Pepper v Hart [1993] AC 593, HL(E)

This case changed the law by relaxing the existing and inflexible rule prohibiting any reference to Parliamentary material as an aid to statutory construction, instead permitting such reference where legislation was ambiguous or obscure or led to absurdity. This narrow but important exception was held not to amount to any questioning or impeaching of the proceedings in Parliament or otherwise to contravene article 9 of the Bill of Rights 1688.

As indicated by the long list of “Subsequent Cases” in the Citator+ service on ICLR Online, the case has often been considered, and relied upon, which suggests that Parliament is perhaps not always as clear as it means to be, notwithstanding the efforts of parliamentary drafters, whose clarity is always subject to the whims of amendment by legislators before (or after) reaching the statute book.

The case is the subject of the Pepper v Hart Research Course, run by the British and Irish Association of Law Librarians (BIALL) at Lincoln’s Inn and delivered by the Inn’s librarian, Guy Holborn, whose involvement in the case dates back to the assistance he provided both counsel involved in their preparations for the hearing.

We’ll conclude our exploration of the cases voted for by you, the readers, in a final post in this category (Historic Cases) on the ICLR blog in the next day or two.

And remember you can read the judgments (and PDFs of the case reports) of all the shortlisted historic cases on BAILII here.

> Back to 150 Years of Case Law on Trial