Banksy under the hammer: graffiti and the law

The news that a piece of London street art attributed to Banksy was to be auctioned in Miami has thrown up all sorts of interesting legal issues, as highlighted in a recent episode of Law in Action. According to the Guardian report of the proposed sale, “Unknown hands prised the artwork, entitled Slave Labour and… Continue reading

The news that a piece of London street art attributed to Banksy was to be auctioned in Miami has thrown up all sorts of interesting legal issues, as highlighted in a recent episode of Law in Action.

According to the Guardian report of the proposed sale,

“Unknown hands prised the artwork, entitled Slave Labour and showing a small barefooted boy making Union Jack bunting in a sewing machine, from the wall of a Poundland shop in Wood Green last week.”

It was being sold by Fine Art Auctions Miamiwith a guide price of $500,000 and $700,000 (£323,000 to £452,000).

It was being sold by Fine Art Auctions Miamiwith a guide price of $500,000 and $700,000 (£323,000 to £452,000).

The work is said to have appeared in May last year, and to be a satirical commentary on the Queen’s jubilee celebrations. That said, it could just as easily be a commentary on the idea of work for welfare, or even the Cool Britannia phase of the Blair premiership. The shop’s name “Poundland” seems an ironically appropriate association.

Presumably the title “Slave Labour” has been applied to the artwork by someone other than Banksy himself, since Banksy (whoever he is) does not seem to have either claimed authorship or approved (or condemned) the sale.

If he wanted to claim authorship, he could assert his moral right in accordance with section 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author, and to the integrity of his work, as well as his copyright in the artwork under Part 1 of the Act, and could complain about any interference with those rights. But, having painted it onto someone else’s wall, he cannot claim ownership of the physical object of the work, which belongs to the owner of the building. If the owner of the building wanted to paint over the work, he would be entitled to do so; and if he wanted to prise it off the wall, much as one removes ancient frescoes from the walls of Italian chapels (at considerable risk to the artwork), he could presumably do so, notwithstanding the artist’s moral rights. But the news report does not make clear whether this is actually what happened, or whether the removal of the work was the act of a third party. If unauthorised, it would constitute the tort of conversion, as well as being a crime of theft.

Might the act of its removal have been the work of the author himself, though, as an extension of the original composition by way of some kind of performance activity? Could the whole business of auctioning the work in fact be part of the work itself? Certainly, the original creation of the work in situ involves an element of performance. Watching Banksy’s film, Exit Through The Gift Shop, one is tempted to argue that his whole life is a sort of performance. As the distinguished art critic and historian Witold Gombrich argued (in The Story of Art): “There is really no such thing as art. There are only artists.” Whether you regard him as a street artist or a con artist, Baksy is undoubtedly an artist.

That said, the creation of a work of street art, save where prior consent has been obtained from relevant parties, constitutes vandalism, ie a form of criminal damage. It is also categorised as an example of “anti-social behaviour” for the purposes of Chapter 1 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, which created ASBOs (see Home Office: A Guide to Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, p 6). In R v Brzezinski [2012] EWCA Crim 198 a sentence of 18 months’ imprisonment for criminal damage by way of graffiti was upheld by the Court of Appeal, Criminal Division.

And yet, in Banksy’s case at least, the very parties whom you would expect to take this view, seem to run as fast as they can in the opposite direction. Local authorities, in particular, seem over anxious to appease the liberal conscience according to which even the most worthless disfigurement of the urban landscape must somehow be acknowledged as a form of self-expression which it would be rather oppressive to regard as mere criminality.

True to form, the good burghers of Haringey, where the Poundland ex-muration took place, represented by local councillor Alan Strickland, launched a campaign to halt the sale, even writing to the Arts Council seeking an urgent ban on the artwork’s export.

“People all over the country are rightly disgusted that a gift to the community could be privately sold for huge profit in this way and are demanding that the auction house abandons or postpones the sale and returns the artwork to Wood Green,” he [Mr Strickland] said in a letter to Sir Peter Bazalgette, chairman of the Arts Council of England.

Leaving aside the question whether people across the nation really feel that strongly about the alleged “gift to the community”, or are in fact stifling their giggles at this bonfire of vanities, there does not seem to be any legal basis on which to prevent a lawful sale by the lawful owner, if such it be. Regulations intended to protect notable works of art don’t apply to recently daubed graffiti, however much one might wish they did. And just how edgy would such artworks be, if they enjoyed such protection? One can imagine Banksy himself, the great épateur of the bourgeoisie, packing up his stencil kit and spraycans in disgust.

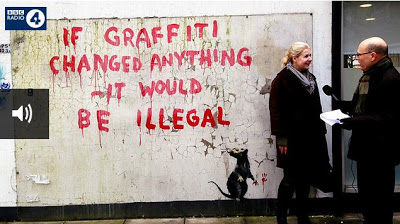

Perhaps he has already expressed his view on the question of tameness, in this piece (left), the subject of Joshua Rozenberg’s discussion of the issues with Johanna Gibson, Professor of Intellectual Property Law at Queen Mary University, London.

Late Reprieve

According to Reuters, Slave Labour and another mural attributed to Banksy were pulled from the sale at the 11th hour by Fine Art Auctions, despite claims that all “due diligence” had been done. Since its removal, Slave Labour has been replaced with another mural, or rather several murals, one of which warns “Danger – thieves” and another depicts the telltale rat holding a note asking “Why?”

Ask an obvious question…