Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR, 30 November 2020

This week’s roundup of legal news and commentary includes a fresh round of coronavirus regulations, more funding for justice (but perhaps not enough), presidential pardons, rape myths, professional misconduct, and racist police raids.… Continue reading

UK Politics

Spending review

The Ministry of Justice has announced that “almost £4.4 bn will be invested to increase court capacity, create prison places, and support victims” following the latest spending review by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak.

This largesse is not unwelcome, but it may not have been distributed to all the parts of the system that need it. For example, “an extra £4 billion will be provided over the next four years to make significant progress in delivering 18,000 additional prison places”. This is great, though existing prison places are desperately in need of improvement and refurbishment (and to be fair, £315m is promised “to enhance the condition of the existing prison estate”); but even when you’ve got all those prison places, how are you going to fill them? You need courts, and you need lawyers and judges in those courts.

So while the announcement talks of “£337m extra funding [to] support the government’s crime agenda — delivering swift and effective justice to convict offenders, support victims, and protect the wider public”, what this amounts to in more detail is “£275 million to manage the impact of 20,000 additional police officers and reduce backlogs caused by the pandemic by increasing capacity in courts, particularly the Crown Court”. There’s also £76m promised towards increasing capacity in the Family Court and Employment Tribunal.

There’s no mention of legal aid, however, or of increasing judicial sitting days, both of which will be necessary if any increased capacity in the criminal courts is to be beneficial. Moreover the boosting of capacity in both civil and criminal courts follows a long period of unprecedented court closures; a bit like the often-trumpeted recruitment of 20,000 police officers, which again followed a period of years during which numbers were substantially reduced. (The same is true of prison officers.)

Coronavirus

Lockdown will end in tiers

The current boom in statutory instruments seems likely to continue unabated as yet another bunch of Coronavirus Regulations comes into force to mark the transition from a second national lockdown in England to a revised version of the preceding tiered system of (slightly) more localised restrictions falling within one of three tiers or levels of severity, depending on the anticipated level of infection in that area. The relevant areas are quite large — county sized rather than town or borough sized, which is something that has caused controversy.

So the The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (No 4) Regulations 2020, which came into force on 5 November 2020, will be replaced by the The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (All Tiers) (England) Regulations 2020, which come into force on 2 December 2020. According to the explanatory note of the latter:

“These Regulations impose restrictions on gatherings and on businesses in England. Areas which are not specified in Schedule 4 are subject to the restrictions set out in Schedule 1. Areas specified in Part 1 of Schedule 4 (those areas in Tier 2) are subject to the restrictions set out in Schedule 2. Areas specified in Part 2 of Schedule 4 (those areas in Tier 3) are subject to the restrictions in Schedule 3. The restrictions on businesses include the imposition of restricted hours for certain businesses and closure of certain businesses.”

The government has also issued guidance, which is not law, but should be followed anyway because it is the right thing to do, says Adam Wagner, the human rights barrister who, via his Better Human podcast and on Twitter, has made the process of explaining successive iterations of the coronavirus regulations his speciality in recent months.

No there are more linked households:

💁♀️1 adult

🧒🧒1+ children (no adults)

💁♀️🧒1 adult and 1+ chid/ren

💁♀️👨⚕️👶1+ adult/s and 1 child under 1 as at 2 Dec or after

👨⚕️💁♀️🧑🦽1+ adult & child with disability under 5

👨⚕️💁♀️🧑🦽1 adult & person with disability requiring constant care pic.twitter.com/MxQ8nQOWkd— Adam Wagner (@AdamWagner1) November 30, 2020

Another statutory instrument, The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Local Authority Enforcement Powers and Amendment) (England) Regulations 2020, updates the power of local authorities and others to enforce the restrictions, eg against businesses who fail (or refuse) to comply.

See also:

- UK Human Rights Blog, Does the lockdown breach the right to freedom of religion?

- Law & Religion UK blog, New COVID-19 legislation and guidance to 5 December

Low resistance and no immunity

Opposition to the coronavirus restrictions has been vocal and there have been some protests, including in London over this last weekend, during which a number of arrests were made. However, there has so far been rather less in the way of litigation than might have been expected.

The main case has been Dolan v Secretary of State for Health and Social Care [2020] EWHC 1786 (Admin), in which a businessman called Stephen Dolan challenged the legality of the original coronavirus restrictions, imposed by the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 (which came into force on 26th March 2020). Permission to claim judicial review was refused by Lewis J on 6 July 2020, and an application to the Court of Appeal was heard in October. Judgment was reserved and is still pending.

UPDATE: 1 DECEMBER — Judgment has today been given, allowing the appeal in part, on the limited ground that, although the claim was academic because the regulations challenged had since been amended or replaced, the question of vires (whether there was power to make them) was of public interest: [2020] EWCA Civ 1605. However, on this ground the claim failed (para 78):

“we have come to the conclusion that, although permission to bring this claim for judicial review should be granted, in view of the public interest in the resolution of this important issue, the correct construction is that the Secretary of State did have power to make the regulations under the 1984 Act, as amended in 2008.”

No doubt there will be more detail commentary anon (perhaps by BarristerBlogger Matthew Scott, who tweeted about it here). There are some other cases in which coronavirus measures have been in play, though less centrally.

In R (Adiatu) v HM Treasury [2020] EWHC 1554 (Admin); [2020] WLR(D) 352 the claimant challenged certain decisions made by the Treasury in relation to the availability of support by way of Statutory Sick Pay (“SSP”) and the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (“JRS”), alleging that they are being applied in a discriminatory way. It is not a challenge to the legality of coronavirus restrictions per se.

More recently, in R (Article 39) v Secretary of State for Education [2020] EWCA Civ 1577; [2020] WLR(D) 632 the claimants challenged the reliance of the government on the health emergency in failing to consult the Children’s Commissioner and other bodies representing children’s rights, before making changes to the regulation of social care services in order to deal with the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the children’s social care system under the Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations 2020. Though the judge dismissed the claim, it was allowed on appeal.

There has also been a challenge to the practice direction suspending eviction claims by landlords against tenants for (initially) 90 days, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic: see Arkin v Marshall (Housing Law Practitioners Association intervening) [2020] EWCA Civ 620; [2020] 1 WLR 3284; [2020] WLR(D) 330, about which a lot of landlords are not very happy.

These are all cases that appear to have some legal merit, even if not ultimately successful. But there are other cases which appear to be less well grounded. These are cases in which jurisprudential autodidacts have taken it upon themselves to ignore the constitutional principle that Parliament cannot bind its successors and to rely on the statute implementing a revised version of the treaty between King John and his barons, conventionally known as Magna Carta, to trump, as it were, all subsequent legislation (such as the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984) enabling the making of coronavirus regulations and conferring powers on the police and local authorities to enforce them. Shop owners have declared or been assured that by posting a copy of a notice citing Magna Carta in their windows, and declaring that they are only bound by the common law on the basis of contractual consent, they can evade the enforcement of restrictions on their ability to operate their business and serve customers. The courts have not been convinced of the value of Magna Carta as a “get out of jail free” card, such as one might obtain by chance in the board game Monopoly. (Indeed, the courts would appear to have a monopoly on the final determination of criminal offences under the relevant regulations.)

This belief in the magical powers of Magna Carta and the common law is, as the Secret Barrister explains in a recent blog post,

“a species of what regular attendees at courts will recognise as the pseudo-legal rubbish peddled by self-styled “Freemen on The Land”, a grouping of proselytising individuals who believe that by misquoting Magna Carta and basic tenets of contract law, they can somehow place themselves outside the jurisdiction of the law of England & Wales.”

It is, of course, doomed to failure. See: Can Magna Carta and “common law” give you immunity from Covid regulations?

Crime

Rape myths

Belief by juries in rape myths is a myth, according to new findings published by the UK’s leading academic expert on juries, as Joshua Rozenberg reports in a recent post on A Lawyer Writes. The findings were published by Professor Cheryl Thomas QC (hon), director of the Judicial Institute at UCL, University of London, in a paper published last month in Criminal Law Review: see Thomas, C; The 21st century jury: contempt, bias and the impact of jury service [2020] Crim LR 987–1011.

“The overwhelming majority of jurors do not believe that rape must leave bruises or marks, that a person will always fight back when being raped, that dressing or acting provocatively or going out alone at night is inviting rape, that men cannot be raped or that rapes will always be reported immediately.”

Rozenberg contrasts her findings with the assertions made by campaigners in support of a petition to Parliament in 2018. It was in response to that petition that the government commissioned Professor Thomas’s research.

The UCL Jury Project undertook research in 2018–19 to address two key questions: (1) to what extent do real jurors who have served on juries believe rape myths and stereotypes; and (2) should judges provide any additional guidance to jurors on rape myths and stereotypes? She concluded that “previous claims of widespread ‘juror bias’ in sexual offences cases are not valid” and that “hardly any jurors believe what are often referred to as widespread myths and stereotypes about rape and sexual assault”. On the second question, however, she concluded that:

“ this research with real jurors does indicate that some jurors would benefit from additional guidance in two specific areas (stranger vs acquaintance rape and emotion when giving evidence) where some jurors are uncertain of the factual reality and a small number hold incorrect views.”

US Politics

Presidential pardons

The power of POTUS to pardon has been topical for two reasons. First, because as a matter of custom and tradition the President confers a pardon on a turkey to mark the American feast of Thanksgiving at this time of year. Secondly, because the current President, Donald J Trump, recently took the opportunity (albeit not at the same ceremony) to exercise his constitutional power to confer a pardon on someone charged or convicted with a federal offence, namely Michael Flynn, his former national security adviser, who pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI.

Article I, § 2 of the United States Constitution provides the President the authority “to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” It appears that the power can be exercised prospectively, ie before an offence has been charged, perhaps even before it has been committed; but it is not settled as to whether a President can pardon himself, to as to extend the immunity from prosecution (but not impeachment) which he enjoys while in office, if and when he is eventually persuaded to leave his office.

Curiously enough, President Trump appears not to have used his pardon power very much, at least not so far. His immediate predecessor, Barack Obama, granted 212 pardons (and 1,715 commutations of sentence)— the most since President Harry Truman. President Clinton famously pardoned his own brother. If Trump hasn’t got going yet with this, perhaps it’s because he’s been too busy litigating to overturn the election result up with which he has resolved not to put.

The problem with pardons is that they presuppose something to pardon or absolve; to accept a pardon is therefore an admission of guilt. You cannot pardon the innocent. So a pardon is a badge of iniquity, and might not be worth much more than a free turkey.

For more on this, see:

- Congressional Research Service, Presidential Pardons: Overview and Selected Legal Issues and Frequently Asked Questions

- David Allen Green, Pardons should be how mercy complements justice — but what happens when pardons undermine justice?

- BBC, Michael Flynn: Trump pardons ex-national security adviser

Legal professions

Disciplinary sanctions

The case of Ryan Beckwith, a city solicitor from a big firm, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, whose £35,000 fine for breaching professional conduct rules was overturned by the High Court has attracted some attention and commentary. Beckwith was found by the Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal to have “initiated and/or engaged in sexual activity with Person A”, a female colleague, in circumstances (including drunkenness and Person A’s more junior status, but outside of their work environment) which constituted a breach of principles under the SRA Code of Conduct 2011, namely that a solicitor must: “act with integrity” (principle 2) and “behave in a way that maintains the trust the public places in you and in the provision of legal services” (principle 6). As well as being fined, Beckwith was made to pay costs of £200,000.

The circumstances of the case are not very edifying. However, the point is that he appealed under section 49 of the Solicitors Act 1974 and in Beckwith v Solicitors Regulation Authority [2020] EWHC 3231 (Admin) the Queen’s Bench Divisional Court allowed his appeal, reversed the findings of the SDT, quashed the fine and set aside the costs order.

The court did not accept that the facts justified the tribunal’s conclusions that there had been a breach of the code. They also observed, at para 54:

“There can be no hard and fast rule either that regulation under the Handbook may never be directed to the regulated person’s private life, or that any/every aspect of her private life is liable to scrutiny. But Principle 2 or Principle 6 may reach into private life only when conduct that is part of a person’s private life realistically touches on her practise of the profession (Principle 2) or the standing of the profession (Principle 6). Any such conduct must be qualitatively relevant. It must, in a way that is demonstrably relevant, engage one or other of the standards of behaviour which are set out in or necessarily implicit from the Handbook. In this way, the required fair balance is properly struck between the right to respect to private life and the public interest in the regulation of the solicitor’s profession. Regulators will do well to recognise that it is all too easy to be dogmatic without knowing it; popular outcry is not proof that a particular set of events gives rise to any matter falling within a regulator’s remit.”

The tribunal’s approach was criticised by Prof Richard Moorhead on the Lawyer Watch blog, in The Beckwith Case and Beckwith 2: the SDT’s card should be marked; but the court’s judgment is also criticised, by Prof Stephen Vaughan in another post on the same blog, Personal Lives and Professional Principles: Beckwith, Integrity and the High Court. Vaughan suggests that a further appeal may be in the offing.

See also: Nick Brett (who appeared for Beckwith), via Inforrm’s blog, Divisional Court overturns Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal in “inappropriate sexual activity” case and warns against the regulation of private lives

Below the Bar

Meanwhile, a barrister who was found guilty of “upskirting” (a form of voyeurism offence) has been suspended from practice for six months by the Bar Disciplinary Tribunal. Daren Timson-Hunt was found to have behaved in a way that diminished public trust and confidence in the profession and which could reasonably be seen by the public as undermining his integrity, contrary to Core Duty 5 and Rule rC8 of the BSB Handbook, after being convicted of an offence under section 67A(1) and (4) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (as inserted by sections 1 and 2 of the Voyeurism (Offences) Act 2019).

According to Legal Futures, he admitted the offence at Westminster Magistrates’ Court in September last year and was sentenced to a 24-month community order with a 35-day programme requirement, 30 days of rehabilitation activity and 60 hours unpaid work. He was also placed on the sex offenders register for five years.

He told the court that he had been under stress at work, as head of the EU exit and goods legal team at the Department for International Trade, and apologised to the victim. However, she told the court that the incident had deeply impacted her day-to-day behaviour — preferring not to wear a dress or skirt — and made her avoid public transport.

As well as being criticised by lawyers on Twitter for the leniency of the six-month suspension, the case was compared unfavourably to the rather more robust professional sanction imposed on a police officer for an offence of dishonesty (underpaying for donuts at a shop), who was sacked for gross misconduct:

Interesting comparison here with another story this week.

Police officer steals donuts = sacked for gross misconduct

Barrister commits offence of upskirting = 6 month suspension, then as you were, pal

Doesn’t reflect well on the Bar.https://t.co/v57VMk762U

— The Secret Barrister (@BarristerSecret) November 26, 2020

It might also have been compared to the case of Ryan Beckwith (above), had his appeal not been allowed.

Recent publications and broadcasts

Mangrove

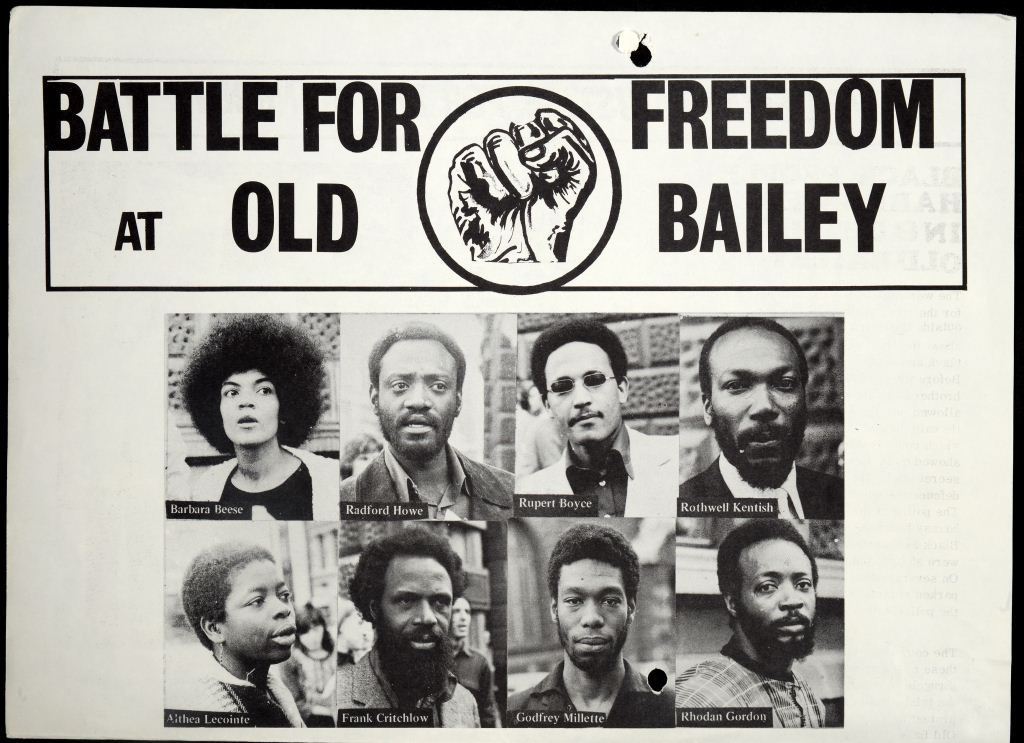

The first in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series of films for the BBC about London’s West Indian community tells the true story of the Mangrove restaurant, a lively community hub in London’s Notting Hill that was the subject of relentless (and racially motivated) police raids during the 1970s, and the trial of its owner, Frank Critchlow, and a number of activists following a street protest. The trial took place at the Old Bailey, lasted 55 days, and resulted in humiliation for the police and acquittals on all the main charges for the activists (many of whom had represented themselves).

Watch the episode: Mangrove (BBC 1, iPlayer)

Background reading:

- BBC News, The Mangrove Nine — Echoes of black lives matter from 50 years ago

- The Critic, The trial of the Mangrove Nine

- The Guardian (from 2010), Mangrove Nine: the court challenge against police racism in Notting Hill

- The National Archives, Rights, resistance and racism: the story of the Mangrove Nine

Fake Law: An Evening with the Secret Barrister

The Human Rights Lawyers’ Association put on an entertaining discussion with the Secret Barrister on 24 November (words spoken by another barrister), along with Shoaib M Khan, Joanna Hardy and Joshua Rozenberg. They discuss issues raised in two recent books by members of the panel, Fake Law by the Secret Barrister and Enemies of the People by Joshua Rozenberg, including respect for the rule of law, the judiciary and “activist” lawyers, and how they are regarded in the media.

What About Me? Reframing Support for Families following Parental Separation

Alice Twaite via the Transparency Project writes about the recent report of the Family Solutions Group, entitled What about me?: Reframing Support for Families following Parental Separation.

Internet Newsletter for Lawyers

The latest edition of the Internet Newsletter for Lawyers, November / December 2020, is now out, containing articles about data protection, employee privacy, mutant algorithms, the ICO’s investigation of Cambridge Analytica, and an explainer on the Domain Name System (DNS). The newsletter, edited by Nick Holmes, can be read online or downloaded as a PDF. Hard copies are sent out to subscribers.

Review into bias in algorithmic decision-making

The Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) has published the final report of its review into bias in algorithmic decision-making. The review looks at the use of algorithmic decision-making in four sectors (policing, local government, financial services and recruitment) and makes cross-cutting recommendations that aim to help build the right systems so that algorithms improve, rather than worsen, decision-making. These sectors were selected because they all involve significant decisions about individuals, and because there is evidence of both the growing uptake of algorithms and historic bias in decision-making in these sectors.

The measures that the CDEI has proposed are designed to produce a step change in the behaviour of all organisations making life-changing decisions on the basis of data, with a focus on improving accountability and transparency. Read more:

- Review into bias in algorithmic decision-making

- Summary slide deck: Review into bias in algorithmic decision-making

Dates and Deadlines

The future of Parole: Problems and solutions webinars

Online: 8 and 9 December 2020, between 5–7 pm

The Parole Board is holding two online events with Cambridge Centre for Criminal Justice and the Institute of Criminology to explore the future of parole. Parole Board Chair Caroline Corby and CEO, Martin Jones will speak at the event alongside other experts including; Professors David Feldman, Nicky Padfield, Rob Canton, Julian Roberts, and Simon Creighton, of Bhatt Murphy. To register for the events, please follow the links below:

And finally…

Tweet of the week,

reflects rather less well on the Chancellor’s spending plans than the story at the top of this roundup. However, Martin Shovel’s cartoon could also apply to a number of other developments over the year, such as the UK Internal Market Bill.

My cartoon – the level of overseas aid is enshrined in law… so let’s cut it! pic.twitter.com/HhiWP3laeb

— Martin Shovel (@MartinShovel) November 29, 2020

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading, and thanks for all your tweets and links. Take care now.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.