Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR, 18 March 2024

This week’s roundup of legal news include extremism defined, immigration data, AI technology and more. Plus recent case law and commentary.… Continue reading

Public order

Extremism defined

“Extremism is the promotion or advancement of an ideology based on violence, hatred or intolerance, that aims to:

(1) negate or destroy the fundamental rights and freedoms of others; or

(2) undermine, overturn or replace the UK’s system of liberal parliamentary democracy and democratic rights; or

(3) intentionally create a permissive environment for others to achieve the results in (1) or (2).”

Such was the new definition of extremism announced by the Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities last week. The definition updates the one set out in the 2011 Prevent Strategy and reflects the evolution of extremist ideologies and the social harms they create. It acknowledges that most extremist materials and activities are not illegal and do not meet a terrorism or national security threshold. So the purpose is not to censor or punish people expressing extremist views, but rather to use the definition to trigger engagement, avoid inadvertent support, and prevent the relevant ideologies spilling over into violence or other problematic behaviour. According to the announcement,

“The definition and engagement principles will be used by government departments to ensure that they are not inadvertently providing a platform, funding or legitimacy to individuals, groups or organisations who attempt to advance extremist ideologies.”

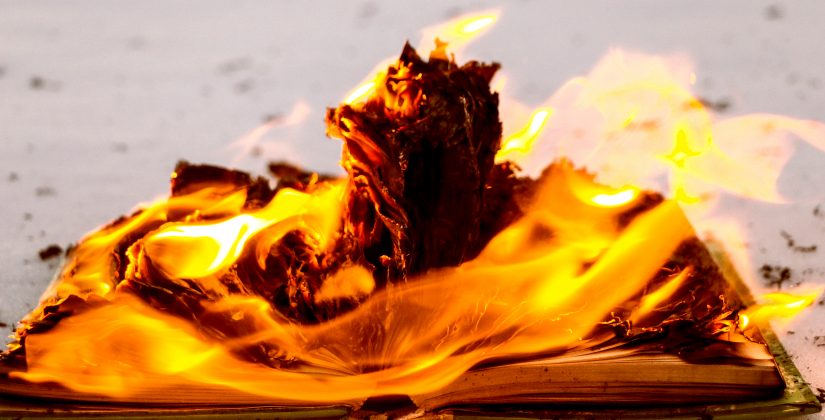

The vagueness of the definition is evident as soon as you consider, for example, whether traditional Christian views about homosexuality might be caught. Such views, based on a particular understanding of ancient Biblical prohibitions, would constitute “the promotion or advancement of an ideology based on … intolerance, that aims to … negate or destroy the fundamental rights and freedoms of others”. While the government may find such intolerance inconvenient and tiresome, its purpose seems to be to prevent such views spilling over into more problematic behaviour, such as “using, threatening, inciting, justifying, glorifying or excusing violence”. An example might be the intolerance of freedom of expression that escalated from the burning of Salman Rushdie’s novels to the fatwa against his life and the death and injuries that followed.

The announcement sets out a number of examples of such “behaviour that could constitute extremism” — unlawful conduct inspired or encouraged by extremism — which it says are an important guide to its application: “understanding the intention behind the behaviour when assessing for extremism risk is key”.

In a statement recommending the definition to the House of Commons on 14 March 2024, the Secretary of State Michael Gove MP said:

“Our plans, drawn up in close collaboration with the Home Office, will enable the Government to express more clearly than ever before which groups fall within the extremism definition, point to the evidence, and explain the funding and engagement consequences. They will also support national efforts to counter the work of extremists who promote their ideologies both online and offline. The new definition will strengthen vital frontline counter-radicalisation work.”

Not everyone sees things the same way:

- Law & Religion UK: The UK Government’s new definition of “extremism” (and the reaction of church leaders)

- The Jurist: UK government releases new definition of ‘extremism’

- Educate against Hate: Terrorism and Extremism

- The Guardian: Three Tory ex-home secretaries warn against politicising anti-extremism

- Le Monde: UK government presents divisive new definition of extremism

- Amnesty International: Government’s extremism definition is a ‘smash and grab’ on our human rights

Immigration

Data confusion

Major flaws in a huge Home Office immigration database have resulted in more than 76,000 people being listed with incorrect names, photographs or immigration status, according to The Guardian.

“Ministers have denied there is a ‘systemic’ problem with Atlas, the tool used by border officials and immigration officers which operates off the flawed database. Documents seen by the Guardian, however, shed light on the department’s attempts to remedy a widespread problem that is causing people’s data to be mixed up, often with that of complete strangers.”

The new Atlas system was already behind schedule when the National Audit Office published its report on The asylum and protection transformation programme (HC 1375) last summer.

“At the time of our fieldwork, asylum caseworkers told us they had to use two systems to enter or update the same information. Weaknesses with the technology mean that the Home Office does not have all the data it requires to manage the Programme effectively.”

The transformation programme aims to build an asylum system that is “fair, supportive and efficient”, but has been beset with problems. Its three phases were, first to stabilise the system (by March 2023); second, to digitise the system (by March 2024), and then finally to optimise (by March 2025). It seems the problems are with the digitise phase, and the use of two systems to enter or update the same information has a horrible echo of the problems the HMCTS has been having with the Common Platform and its recent decision, reported here, to combine and integrate the old DCS platform rather than replace it altogether. While implementing Atlas, according to the NAO, “Asylum caseworkers told us they used both systems and had to ‘double key’ information between them”.

The NAO report was primarily focused on the Home Office’s attempts to clear the backlog of asylum claims which had accumulated while its attention was distracted with the Rwanda scheme and attempts to “stop the boats”. But it seems that glitches in the system may now be affecting some 76,000 people, with the wrong passports and other personal details, including photographs, being mixed up with those of other people.

See also: UKAuthority, Technology trouble undermines Home Office asylum programme says NAO

EU unsettlement

The EU settlement scheme is also having IT problems with its online “proof of status” portal, which a report from Justice says means

“even those who have secured the right to live and work in the UK sometimes have no way to prove this, leaving them needlessly missing flights, job opportunities, and housing rental options”.

The report Reforming the EU Settlement Scheme: The Way Forward for the EUSS, from a working group chaired by Paul Bowen KC, noted that the scheme has had some notable successes — not least by handling applications from over 6 million people. But the report identified a number of ongoing problems with the scheme:

- Applications are regularly wrongly refused — often due to Home Office caseworkers struggling to understand and consistently apply overly complex guidance. But such decisions are difficult to remedy, particularly with the recent removal of the Home Office’s internal system for reviewing decisions.

- Unmarried partnerships and young dependents’ family relationships are judged using outdated and culturally exclusive criteria such as financial dependency.

- Domestic violence victims face particular difficulties safely accessing their status (in one case, for example, the Home Office mistakenly gave a woman’s abusive partner access to her ‘proof of status’ portal despite knowing that her and her child had moved to a safe house.)

- People without formal documents like bank statements or council tax records face a far higher bar to prove UK residency despite guidance stating that caseworkers should take a variety of evidence as valid.

The report makes 16 recommendations to strengthen the scheme, which it hopes “will be carefully considered and adopted”.

See also: UK In a Changing Europe, Citizens’ rights and computer glitches: is digital immigration status fit for purpose?

Technology

AI in government and the law

The National Audit Office (NAO) has published a report on the Use of artificial intelligence in government (HC 612). It considers how effectively the government has set itself up to maximise the opportunities and mitigate the risks of AI in providing public services.

Last year the Central Digital and Data Office (CDDO), a division of the Cabinet Office, began work with the Department for Science, Innovation & Technology (DSIT) and HM Treasury to develop a strategy for AI adoption in the public sector. Specifically, the NAO report looks at:

- the government’s strategy and governance for AI use in public services (Part One).

- how government bodies are using AI and how government understands the opportunities (Part Two).

- central government’s plans for supporting the testing, piloting and scaling of AI; and progress in addressing barriers to AI adoption (Part Three).

The report concludes that AI presents the government with opportunities to transform public services; that AI is not yet widely used across government, but 70% of respondents are piloting and planning AI use cases; and that, to deliver the transformational benefits of AI, the government needs to ensure its overall programme for AI adoption is ambitious and supported by a realistic plan for the skills, funding and wider enablers needed. The government must also maintain focus on addressing other fundamental barriers to AI adoption, such as legacy systems, and data access and sharing, which will otherwise limit the extent to which it can exploit the future potential of AI.

The report does not address regulation of AI, which was the subject of a government white paper, A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation, and addresses risks to fairness, security, human rights, safety, privacy and societal wellbeing. That was published in August 2023. The government’s pro-innovation approach may be contrasted with both the EU’s more risk-based approach, in its AI Act, and the almost complete lack of regulation elsewhere.

These varying approaches to AI regulation are the subject of an excellent podcast by Panopticon, Episode 3: Regulation of AI (featuring Jamie Susskind). The author of The Digital Republic and Future Politics speaks to Leo Davidson of 11 KBW chambers about the pressing need for leaders to get to grips with the social impact of AI and analyses the steps which have been taken to date. It’s entertaining and informative.

The Master of the Rolls, Sir Geoffrey Vos, is well known for his undisguised enthusiasm for AI and lawtech more generally, and his recent speech to the Manchester Law Society’s AI conference on the subject of AI — Transforming the work of lawyers and judges has been widely reported. Unfortunately, the PDF edition to which this link goes does not contain the images generated by Dall-E which Vos appears to have shown his audience, but perhaps that’s no bad thing. (As Susskind says in that podcast, with AI we are at the “things can only get better” stage.) Vos begins by accepting that he is speaking to the converted, but stresses how “incredibly important” it is that “lawyers and judges get to grips with new technologies in general and AI in particular”.

One of his key themes, and one that has been widely reported, is that AI is here to stay and lawyers, among other professions, have to work with it. Indeed, they cannot afford not to:

“One may ask rhetorically whether lawyers and others in a range of professional services will be able to show that they have used reasonable skill care and diligence to protect their clients’ interests if they fail to use available AI programmes that would be better, quicker and cheaper.”

He goes on to describe a number of tasks with which AI can assist lawyers to do their jobs more quickly or efficiently, with the caveat about accuracy which has become increasingly relevant since the launch of Chat-GPT and other free access large language models (LLMs) in the last 18 months. So LLMs are v”ery good at suggesting draft contracts”, and “can also predict case outcomes”. But “early adopters came a cropper” when using AI for the creation of legal advice and court submissions if they failed to appreciate the risks of hallucination (the making up of bogus but plausible case citations, etc). Even here, Vos points out that many of the problems with accuracy stem from the shortcomings in the training data:

“There is, however, no reason why an AI could not be trained only on, for example, the 6,000 pages of the CPR or on the National Archives case law database, BAILLI, Westlaw, or Lexis Nexis, but unable to scrape the bulk of the internet. Such a tool would be likely to give answers that would be more accurate and useful than a public LLM.”

Indeed. Or, we might add, on the nearly 160 years’ worth of case law published by ICLR, on which we have already trained our own AI research tool, Case Genie. (And which is also being used in the development of other products.)

As for the legal profession, in Vos’s view,

“Using AI is unlikely to be optional. First, clients will not want to pay for what they can get more cheaply elsewhere. … Secondly, in a similar vein, if AI can summarise the salient points contained in thousands of pages of documents in seconds, clients will not want to pay for lawyers to do so manually. … Thirdly, and perhaps more importantly, AI is not only quicker, but may do some tasks more comprehensively than a human adviser or operator can do.”

In short, AI is the future and, as the saying goes, the future isn’t optional.

See also: Joshua Rozenberg, Lawyers can’t avoid AI

Legal Futures: Embracing the future: Navigating AI in litigation

Legal Futures: It will soon be negligent not to use AI, Master of the Rolls predicts

Courts

High Court Judicial Assistants Scheme 2024–25

Recently qualified barristers and solicitors in the early stages of their legal career are invited to apply to become judicial assistants in the High Court, at a salary of £37,238. Successful applicants are assigned to judges of the High Court across the three Divisions, providing assistance by carrying out legal research, summarising documents and providing general support in the organisation of their work and hearings. This recruitment round is for the equivalent of up to 13 full-time appointments for the 2024/2025 legal year.

For more details, see Judiciary website.

Court opening times over Easter 2024

Most courts and tribunals will temporarily close over the Easter period, from Friday 29 March to Monday 1 April 2024. They will reopen on Tuesday 2 April 2024.

Some magistrates’ courts will be open on Saturday 30 March and Monday 1 April 2024, but for remand hearings only.

A full list of such courts is provided on the Gov.uk website.

Recent case summaries from ICLR

A selection of recently published WLR Daily case summaries from ICLR.4:

ARBITRATION — Award — Challenge to award: Czech Republic v Diag Human SE, 08 Mar 2024 [2024] EWHC 503 (Comm); [2024] WLR(D) 123, KBD

CONTEMPT OF COURT — Crown Court — Procedure: R v Jordan (John), 12 Mar 2024 [2024] EWCA Crim 229; [2024] WLR(D) 120, CA

CRIME — Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority — Compensation, whether repayable: R (AXO) v First-tier Tribunal (Social Entitlement Chamber), 11 Mar 2024 [2024] EWCA Civ 226; [2024] WLR(D) 112, CA

EMPLOYMENT — Time off for dependants — Parental leave: Hilton Foods Solutions Ltd v Wright, 07 Mar 2024 [2024] EAT 28; [2024] WLR(D) 106, EAT

INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS — Employment Appeal Tribunal — Procedure: Melki v Bouygues E and S Contracting UK Ltd, 13 Mar 2024 [2024] EAT 36; [2024] WLR(D) 117, EAT

INJUNCTION — Anti-social behaviour — Begging: Swindon Borough Council v Abrook, 08 Mar 2024 [2024] EWCA Civ 221; [2024] WLR(D) 110, CA

LIMITATION OF ACTION — Judgment debt — Interest: Deutsche Bank AG v Sebastian Holdings Inc, 14 Mar 2024 [2024] EWCA Civ 245; [2024] WLR(D) 121, CA

PLANNING — Enforcement notice — Validity: Gurvits v Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 06 Mar 2024 [2024] EWHC 490 (Admin); [2024] WLR(D) 119, KBD

PRACTICE — Case management — Alternative dispute resolution: X v Y, 08 Mar 2024 [2024] EWHC 538 (Fam); [2024] WLR(D) 116, Fam D

WATER — Sewerage — Right to charge: Brendon International Ltd v Water Plus Ltd, 08 Mar 2024 [2024] EWCA Civ 220; [2024] WLR(D) 108, CA

Recent case comments on ICLR

Expert commentary from firms, chambers and legal bloggers recently indexed on ICLR.4 includes:

Law & Religion UK: Use of cremation ashes for jewellery (again): Re St. John Seaton Hirst [2024] ECC New 1, Const Ct

NIPC Law: Trade Marks: Lifestyle Equities CV v Amazon UK Services Ltd [2024] UKSC 8; [2024] WLR(D) 105, SC(E)

NIPC Law: The Flitcraft Appeal — Price v Flitcraft Limited [2024] EWCA Civ 136, CA

NIPC Law: Registered Designs — The Appeal in Marks and Spencer Plc v Aldi Stores Ltd: Marks and Spencer plc v Aldi Stores Ltd [2024] EWCA Civ 178, CA

Panopticon: Oral disclosures as acts of data processing: Endemol Shine Finland (Case C-740/22); EU:C:2024:216, ECJ

Panopticon: Equiniti group claim — court strikes out almost all claims: Farley v Paymaster (1836) Ltd (trading as Equiniti) [2024] EWHC 383 (KB), QBD

And finally…

Tweet of the week

Is one of many celebrating #SilksDay:

A proud day for @7BRchambers as Maryam Syed KC, Susannah Johnson KC, @JJBarrister7BR and Anita Guha KC take silk.

Bravo to everyone celebrating #SilksDay and may your listing tomorrow be light and not before 2pm pic.twitter.com/PjdEB2I31j

— Gareth Weetman (@Barrister7) March 18, 2024

Congratulations to all the new silks. And thanks for reading. That’s all for now. Work hard, be kind, take care.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.

Featured image via Shutterstock