Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 16 May 2014

A weekly roundup of topical legal news, including the continuing VHCC saga, a review of criminal advocacy (or what might be left of it), and a torrent of historical “divorce porn” from the new Family Court. But first, that “unforgettable” google ruling from the ECJ. You have a right to remain silent, thanks to Magna… Continue reading

A weekly roundup of topical legal news, including the continuing VHCC saga, a review of criminal advocacy (or what might be left of it), and a torrent of historical “divorce porn” from the new Family Court.

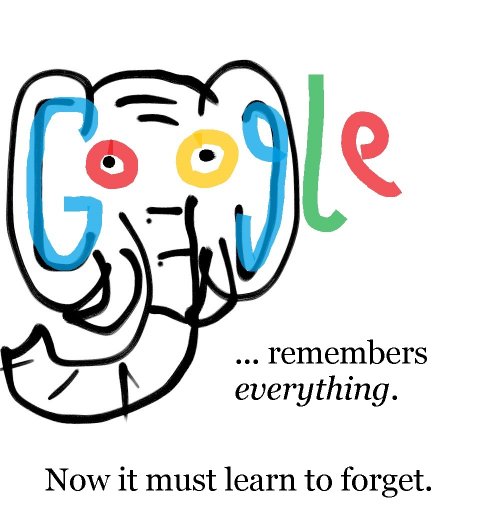

But first, that “unforgettable” google ruling from the ECJ.

You have a right to remain silent, thanks to Magna Carta, and now you have a right to be forgotten — online at least.

This right, exercised with ease by so many characters in popular novels trumpeted as “unforgettable”, may soon be available to non-fictional human beings, in an online context, if the ECJ’s latest ruling affecting Google is both enforceable and enforced (about which some have doubts).

The case originated in Spain, where Mr Costeja González sought to have personal data about him removed from google’s index because it was out of date. The data related to a newspaper report mentioning attachment proceedings for the recovery of social security debts, which he said had long since been resolved and reference to them was now entirely irrelevant. The Spanish Data Protection Agency upheld his claim in relation to google on the ground that operators of search engines are subject to data protection legislation given that they carry out data processing for which they are responsible and act as intermediaries in the information society. That view was essentially upheld by the Court of Justice in Google Spain SL v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) (Case C-131/12); [2014] WLR (D) 202.

Interestingly, as EU Law Analysis points out in its blog, the case was decided on the basis of the EU’s data protection Directive which was adopted in 1995, at a time when the internet was in its infancy – not the more recent Directive proposed (but not yet in force).

In its judgment, the court found, inter alia, that the activity of a search engine consisting in finding information published or placed on the internet by third parties, indexing it automatically, storing it temporarily and, finally, making it available to internet users according to a particular order of preference must be classified as ‘processing of personal data’ within the meaning of article 2(b) of Directive 95/46/EC, that the operator of the search engine was a “controller” of such data within article 2(d), and that, under articles 12 and 14, the individual’s right to have the data removed could override the economic rights of the operator and the interest of the general public in having access to the information.

Though it appears to support the concept of the “right to be forgotten”, the precise ambit of the decision has been the subject of some uncertainty. According to WebProNews,

The Court of Justice of the European Union has ruled that Google and other search engines must delete search results at people’s request in some cases, and it’s up to the search engines to determine when to comply. If an agreement can’t be reached between the search engine and the person requesting the deletion of information, then they’ll have to go to court to sort it out.

Some people have wanted to be able to have information about themselves removed from Google for years, and this is a major development in that storyline. On the other side of the coin, some would say that being forced to get rid of info about people just because they don’t like it amounts to censorship. That’s Google’s argument.

Paul Bernal, Lecturer in Information Technology, Intellectual Property and Media Law at the University of East Anglia Law School, writing for CNN (Google privacy ruling could change how we all use the Internet), explained that:

The “right to be forgotten” is the idea that we have the right to wipe the slate clean, to remove outdated stories such as spent convictions from the record.

There have been versions of this right in a number of European countries — France, Italy, Spain and Germany, for example — for some time, but for the most part in pre-Internet forms, designed to stop newspapers republishing out-dated stories.

The Internet has changed things so much that some suggest the law needs to catch up.

For most people, Google is the main way people find information — so if you can prevent Google from providing links to a story, to a great extent you prevent people from reading that story.”

For more on this story, see also:

Paul Bernal’s own blog, It’s not the end of the world as we know it

LSE Media Policy Project, European Court Rules against Google, in Favour of Right to be Forgotten

EU Law Analysis, The CJEU’s Google Spain judgment: failing to balance privacy and freedom of expression

Legal Aid woes

Operation Cotton saga continues

The “Operation Cotton” saga (see Weekly Notes – 9 May 2014) continued this week as the Court of Appeal heard an appeal by the prosecuting authority, the FCA, against the ruling of Judge Leonard on 1 May staying the complex fraud case of R v Crawley and Others on grounds that a fair trial was not possible because the defendants, who were all legally aided, had been unable to secure legal representation by suitably accredited VHCC (Very High Cost Cases) barristers.

The Secretary of State for Justice sought to intervene in the appeal and all the skeleton arguments of all 3 parties (including the respondent defendants) can be read either on the Jack of Kent blog (see handy guide here) or via Crimeline (PDF here). Among the arguments put forward by the SSJ was that the Public Defender Service, though undermanned at present, would eventually be sufficiently populated with suitably qualified barristers to replace the lost VHCC contingent, but this has been questioned.

Apart from anything else, even on the MOJ’s own figures, it would appear that the PDS is a more expensive option from the point of view of the public purse, than engaging self-employed barristers at the uncut VHCC rates. (See The Cost of the Public Defender Service analysis here.)

Dan Bunting analyses the PDS condundrum on his own blog, here. The PDS Business Plan

He covered the Operation Cotton appeal here, as did Catherine Baksi in the Gazette here, and the live tweeting of the proceedings was turned into a blog via storify by Lucy Reed of Pink Tape fame.

There was also a very good piece by David Allen Green (who writes the Jack of Kent blog) in the Financial Times over the weekend (before the appeal hearing) analysing the causes and consequences of the VHCC fiasco: How a policy failure now means a number of UK complex fraud cases may collapse.

The Jeffrey Review: update

After all that, one might be forgiven for wondering whether, if everyone ends up either working for the CPS or the PDS, the independent criminal Bar will cease to exist. That seems doubtful, but perhaps the legally aided freelance Bar will cease meaningfully to exist. The indefatigable Dan Bunting has analysed the report for Halsbury’s Law Exchange in a piece entitled The Jeffrey’s Review – a challenge to the Bar.

Anyone practising in criminal law will understand a certain weariness on Sir Bill’s behalf when he says that “many of those in the profession to whom I have spoken in the last few months have found it difficult to get beyond the legal aid cuts as an explanation for poor advocacy quality and indeed any other shortcomings in the system”. In fairness to those that he spoke to, it is hard to see how this is not the most significant challenge that the system faces.”

LASPO and LIPS: the Judges Speak Out

In written evidence given by the Judicial Executive Board (PDF) on the impact of the legal aid changes imposed by the

Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, judges complained about the consequential rise in the number of Litigants in Person. The net effect was to shift the burden of cost from paying for lawyers to spending more on the courts and judges, who had to sort out the muddle and anxiety of unrepresented litigants. As the evidence noted:

“There has been a large increase in the number of cases where one or both parties do not have legal representation – most prominently in private law family litigation. Where legal aid has been removed and individuals have become self-represented, the adverse impact upon courts’ administration and efficiency has therefore been considerable.

“The apparent saving of cost by a reduction in the legal aid budget needs to be viewed in context: often it simply leads to increased cost elsewhere in the court system as, for example, anecdotally, cases take longer.

“The judiciary’s perception is that cases which may never have been brought or been compromised at an early stage are now often fully contested, requiring significantly more judicial involvement and causing consequential delays across the civil, family and tribunals justice systems.”

Full story in The Guardian here.

Victorian “Divorce Porn”

In a judgment which is extraordinary even for Sir James Munby, President of the Family Division, in its fascinating diversions down legal history lane, he identified a problem in the law relating to the publication in the press of (generally sordid) details about divorce proceedings. Ostensibly, Rapisarda v Colladon [2014] EWFC 1406; [2014] CN 861 was an application by the Queen’s Proctor to dismiss a large number of divorce petitions and set aside decrees of divorce already granted, on the ground that they had been obtained in consequence of what Sir James described as “a conspiracy to pervert the course of justice on an almost industrial scale”.

A question arose as to the impact of the Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of Reports) Act 1926, section 1 of which which could have limited the ability of the media to report on the matter. Although the same point had come up in Moynihan v Moynihan [1997] 1 FLR 59, Sir James reopened the issue (and took it further) by reference to the history of the 1926 Act. He seemed to adopt a purposive, even robust common sense, approach to its interpretation:

“No doubt it is some imperfection on my part, but I do not begin to understand how the protection of public morality and public decency, or indeed any other public interest, is facilitated by subjecting the reporting of proceedings in open court of the kind that Sir Stephen Brown P was hearing in Moynihan v Moynihan and that I am hearing in the present case to the restraint imposed by section 1(1)(b) of the 1926 Act.”

He concluded that the words in section 1(4) that “Nothing in this section shall apply … to the printing or publishing of any notice or report in pursuance of the directions of the court” gave judges a discretion to permit, by giving a direction, the media to report the whole of the proceedings. Sir James is an enthusiastic supporter of open justice and duly gave a direction allowing (perhaps even encouraging) the media to “publish whatever report of the proceedings which took place before me on 9 and 10 April 2014 they may think fit”.

It was perhaps to help understand why the Act had been enacted in the first place that Sir James spent much of his judgment, portions of which read more like an amusing after dinner speech, on the historical background stretching back into the golden age of Victorian prudery.

As Sir James reminded us in his Remarks on the Family Justice Reforms (see Weekly Notes – 9 May 2014) the origins of the family justice system lay in the creation of the Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes in 1858. Whereas previously such matters had been handled in the secretive privacy of the Ecclesiastical Courts, the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 required witnesses in the Divorce Court to be examined orally in open court.

“The consequence, inevitable if unintended (for many affected to believe that the shame and humiliation of having to endure a hearing in public would deter the bringing of divorce suits, and some even to be astonished by what the evidence in such cases revealed of behaviour in the bedroom), was a torrent of salacious newspaper reporting.”

By a “delicious irony”, the same session of Parliament had passed an Obscene Publications Act to stamp out smut. As Kate Summerscale, in her book Mrs Robinson’s Disgrace: The Private Diary of a Victorian Lady observed,

police officers were seizing and destroying dirty stories under the Obscenity Act, while barristers and reporters were disseminating them under the Divorce Act. ‘The great law which regulates supply and demand seems to prevail in matters of public decency as well as in other things of commerce,’ noted the Saturday Review in 1859.” – The author, she suggests, was James Fitzjames Stephen, later Stephen J – “‘Block up one channel, and the stream will force another outlet; and so it is that the current dammed up in Holywell Street flings itself out in the Divorce Court.'”

Fine upstanding Victorian gentlefolk were aghast. Indeed, Queen Vic herself wrote to the Lord Chancellor to ask if he could not

prevent the present publicity of the proceedings before the new Divorce Court [which] are of so scandalous a character that it makes it almost impossible for a paper to be trusted in the hands of a young lady or boy. None of the worst French novels from which careful parents would try to protect their children can be as bad as what is daily brought and laid upon the breakfast-table of every educated family in England, and its effect must be most pernicious to the public morals of the country.”

There’s plenty more in this vein. King George V was equally disdainful about French novels when complaining of the “repulsive exposure of those intimate relations between man and woman” to boys and girls reading newspapers.

The solution was the 1926 Act, to “prevent injury to public morals”, and the “titillation” of the public by “salacious details brought out in evidence”. A century later, the dam has burst and the floodgates of prurience are well and truly broken open. Sir James concludes his judgment with a plea for this quixotic law to be reviewed (or perhaps simply repealed).

Incidentally, we are pleased to observe that section 1(4) of the Act explicitly excludes from the ambit of its prohibition “the printing or publishing of any matter in any separate volume or part of any bonâ fide series of law reports which does not form part of any other publication and consists solely of reports of proceedings in courts of law.”