Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 11 September 2015

This week’s collection of legal news and related matters includes the legality of drone strikes, the fate of Just Solutions, the future of human rights legislation and the decline and fall of English literature’s most controversial novel. Legality of drone strikes Is there a Kill List? The announcement by David Cameron in the House… Continue reading

This week’s collection of legal news and related matters includes the legality of drone strikes, the fate of Just Solutions, the future of human rights legislation and the decline and fall of English literature’s most controversial novel.

Legality of drone strikes

Is there a Kill List?

The announcement by David Cameron in the House of Commons on Monday last week that a remotely operated drone had delivered a fatal missile strike on 21 August against two British citizens fighting with ISIL in Syria has provoked a good deal of speculation as to the legality of the operation. Cameron defended the legality of the action saying Reyaad Khan, a jihadist from Cardiff, had been plotting “barbaric” attacks on UK soil and had been targeted in an “act of self-defence”. But he added the phrase “after meticulous planning” which suggests something more deliberate than a reflex action against a sudden, imminent threat. Indeed, the Sun’s report of the case asserted

Britain’s most wanted jihadi has been taken out by an RAF drone in Syria in an MI6-run ‘kill’ operation that lasted almost three months, The Sun can reveal… [adding that]

The Sun has also learned the RAF and eavesdropping spy service GCHQ painstakingly waited weeks for Khan to leave IS’s capital Raqqa for a safe shot without killing civilians too.”

Cameron said that the Attorney General had given advice to the effect that the action was lawful. However, he has not published that advice so we can only speculate. And plenty of people have been doing so. Some said there must be a “kill list”, while others accused the government of “extra-judicial killings”, which may mean not more than the obvious fact that they were not carried out on the orders of a court, which we knew already, but perhaps also implies a want of legitimacy or legal justification, which is of course the issue.

In three successive posts on his Head of Legal blog, Carl Gardner first expressed the opinion that the Attorney’s advice must have been correct and the action was indeed lawful: Law and the killing of Reyaad Khan

He bases his analysis mainly on article 51 of the UN Charter which permits states to take action in self defence, and which he says applies even where the anticipated attack comes from a non-state assailant or from within a state which is powerless (as Syria seems to be) to prevent it.

In a subsequent post, The killing of Reyaad Khan: Britain’s letter to the UN, he discusses the letter which was sent (as required by article 51) to the UN, which appeared to suggest that Britain was relying not only on its own collective self-defence but also that of Iraq, on whose behalf it is currently fighting against IS IL in Iraq (but not Syria). He points out that these justification are not mutually exclusive and the apparent addition of a further ground did not render the first bogus.

This was a point supported by Spinning Hugo on his blog Drone Strikes in Syria.

In his third post, If you think it was murder, say so, Gardner took issue with the phrase “extrajudicial” as used by critics of the government’s claim to legal justification. Citing George Orwell’s complaint about the use of long Latin and Greek derivations rather than plain English words as a way of obscuring humbug and sinister euphemism, he argued that if what these critics really meant by “extrajudicial” was “unlawful” then they should use the word “murder”.

Writing in the Guardian (Was it lawful for UK forces to kill British Isis fighters in Syria?), Joshua Rozenberg also expressed the opinion that the drone strike had been lawful under article 51 of the UN charter. There was evidence of the targeted individuals planning and directing armed attacks against the UK, and the attack appeared to conform to the requirement to be necessary and proportionate.

Sounding a rather more cautious note, David Allen Green in his FT blog, asked When does the UK government have licence to kill?

the legal problem with the killing of Khan is that to invoke Article 51 of the Charter is to perhaps push “self-defence” beyond the limits of elasticity. Article 51 is not a general “licence to kill” terrorists on sight wherever in the world they may be found …

If the UK government wants to re-introduce a general “shoot to kill” policy, but one using drones rather than snipers, then it should say so plainly. The UK government should not hide behind legalistic invocations of Article 51. A “licence to kill” is the stuff of spy fiction, not of foreign policy.

Shashank Joshi, in Prospect magazine, Was David Cameron’s Syria drone strike legal?, is also less than convinced by the article 51 argument, even on behalf of Iraq. He compares the action to that taken by the SAS in Gibraltar against three members of the Provisional IRA in 1988.

If Syria is a legitimate battlefield—on the basis of the collective self defence of Iraq—then IS fighters, British or otherwise, might be considered legitimate. [However…]

Under Cameron’s argument of basic self defence, the government’s position depends on its claim that Khan was plotting an attack—a claim that it will struggle to substantiate properly without releasing secret intelligence. Given the large number of Britons fighting with IS, some—like Mohammed Emwazi—in highly prominent ones, this is an issue that is sure to recur, even if the government fails to get its way on expanding the broader campaign into Syria.

Completely unconvinced, at the other end of the spectrum of speculation, was Clive Stafford Smith, in Huffington Post, who wrote It Is Deeply Disturbing When the Rule of Law Is Jettisoned, and a Politician Decides Who Should Die at the Touch of a Button:

The PM and his Attorney General approved the ‘hit’, and now we are told that some legal theory related to self-defence justified the decision.

… despite Downing Street denying the existence of its own ‘kill list’, we learned that the UK has just this – a list of people we plan to kill in secret. Once again, our principles risk becoming the main casualty in the War On Terror, as we jettison 800 years of the rule of law.

The “kill list” idea was also subscribed to in a Guardian report about Jeremy Corbyn (cometh the hour, cometh the man, you might say – no one would have mentioned his involvement a year ago) having “led a cross-party group of MPs who raised doubts about the change in strategy.”

However, David Davis was also among those questioning the policy:

“They appear to have now a kill list policy. The implication of that is that there is an explicit policy to do it which is a major change from anything we have done previously. It does look unfortunately like the US policy which is ill considered.

“Frankly, if such a policy exists they really ought to come to the house and report on it. They can perfectly properly turn round and say we are not going to comment on individual cases. But actually the principle of what they are doing is a matter the house should consider.”

There’s also a more academic discussion of The Legal Questions About the UK’s Drone Strike in Syria by Noam Lubell, Professor in the School of Law, University of Essex, on the Just Security forum.

Fitting end to Just Solutions

Commercial arm of MOJ shut down

Among the more widely praised decisions taken by Michael Gove after becoming Secretary of State for Justice was that announced last week to the effect that Just Solutions International is to cease to operate. JSi was established in 2012 to sell to foreign governments British expertise on legal and penal affairs. However, in a written statement about JSi’s future, Andrew Selous, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Justice, explained that one project could not be stopped, namely the one “to conduct a training needs analysis for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia prison service staff”. That was because the bid had been subject to a penalty clause to which MOJ would be liable if it pulled out now.

David Allen Green has written often and without mercy about this ignoble venture to sell prison expertise to a regime that routinely chops people’s heads off and flogs them and whose human rights record is dreadful, and he does not pull his punches in his latest post on the subject, in the FT, entitled Gove’s Saudi problem and how he should solve it. (He suggests calling their bluff and letting them see if they can actually enforce their odious penalty clause in the courts.)

Human Rights

Full steam ahead for repeal of Human Rights Act and replacement with British Bill of Rights

The Ministry of Justice confirmed on Tuesday last week that it would “bring forward” proposals for a British Bill of Rights to replace the Human Rights Act “this autumn”, according to a report in the Law Society Gazette. However, no one has actually seen a draft of the Bill, which was a key Conservative party Manifesto commitment.

The matter was the subject of a debate on Thursday evening at Gray’s Inn organised by the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBA HRI), under the title Human Rights: can we go it alone?. Keir Starmer QC MP presented the case for retaining the Human Rights Act 1998 and the connection with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, and Martin Howe QC presented the argument for replacing it with a less deferential and more robust Bill of Rights. Your reporter attended the debate and made a full note of argument, which you can read on this blog here.

Also worth reading

A very interesting discussion by Thomas Roe QC of 3 Hare Court on the subject of Dissenting Judgments

Lady Chatterley

Nitty Gritty – or Utterly Butterly?

Described by the Daily Telegraph as “Lawrence’s steamiest novel”, Lady Chatterley’s Lover enjoys a reputation shared by no other English novel, and yet is doomed to disappoint however you look at it. At the time it was written, it was far too frank about the sexual antics of the two main characters, Lady Chatterley herself, and her gamekeeper, Mellors, with whom she has an increasingly strenuous affair.

Unpublished in the author’s lifetime, it gradually began to circulate via small foreign presses. In the 1950s it became more widely available, especially after a failed prosecution in the United States. At that time, the novel perfectly matched the nitty gritty realism as well as the hypergamous ambitions of the Angry Young Men of working class background busily bedding the girls and (often married) women way above their paygrade.

Then, in 1960, as the angry young men of rock’n’roll gave way to the beatniks of flower power, Penguin books decided to challenge the stuck up establishment by releasing the book, not in descreet hard covers, but a cheap paperback edition. The ensuing trial was a fascinating confrontation between the legal moralists and the libertarian progressives, and also a test of the new Obscene Publications Act 1959, drafted by Norman St-John Stevas, and promoted by Roy Jenkins, which had been designed to permit the publication of works which, while apparently a bit racy, nevertheless exhibited sufficient artistic (or scientific or educational) value to escape the censor’s chopper. (The scientific and educational bit was designed to deal with things like family planning guides, which had previously fallen foul of the more priggish Victorian law: see In re Besant (1878) 11 Ch D 508).

For an account of the trial, told from the viewpoint of junior counsel for the defence (ie Penguin), see chapter 4 of Jeremy Hutchinson’s Case Histories by Thomas Grant, published earlier in this, Hutchinson’s centenary year. The book celebrates a number of his famous trials, of which Lady Chatterley was probably the most famous. (We’ll be reviewing it more fully in due course.)

The verdict of the jury, “not guilty”, caused a sensation. Looking back, it seems inevitable, but at the time it could so easily have gone the other way. Grant suggests the presence of three women jurors played a key part in keeping the deliberations down to earth, and the antagonistic attitude of the judge and the prosecuting silk, both of whom could barely conceal their contempt and outrage as witness after witness was called to testify to the book’s artistic merits, taking advantage of the defence available (and the procedure for relying on it) in the new Act.

Fast forward to the present year, and what do we find? The law is no longer in doubt. Anything goes, pretty much, and nothing matters. Not even authenticity. When the BBC adapts a classic novel for television, the costume department has a field day. The settings must be historically accurate, looming out of the mists of time and beautifully lit with that sunset glow of nostalgia turning the old stone buildings honey-coloured. In short, it must be as utterly butterly as the spread on your dirt brown Hovis loaf, delivered to the sound of a colliery brass band. But as for the dialogue and the plot, who cares? Let’s just see how quickly they can strip off those lovely old tweeds and velvets… Much of the trial was about the authentic use of four letter words: not many of those seemed to remain in the script. Instead, it was more about social inequality than sexual liberation. It was almost as though the trial had never been won, and we’d been served a sanitised, Downtonised version instead. Judge for yourself, if you haven’t already: first broadcast last Sunday, it’s available on iPlayer till 6 October.

And finally… the not entirely serious story

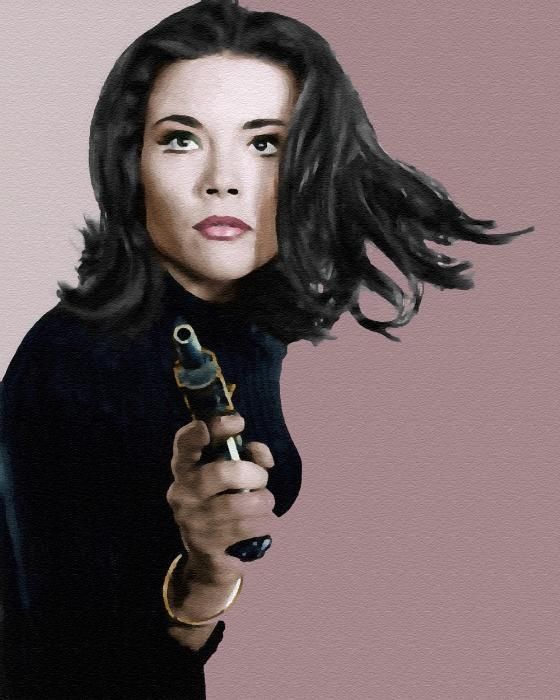

Avengers – new series

Still in the holiday mood, and cool on the heels of Lady Chatterley, here comes another revival from the 60s. Yes, it’s the Avengers, no longer starring Patrick McNee and Diana Rigg, but rather a pair of rank outsiders no one had ever heard of till this week. And in another twist, there’s a thoroughly updated plot. The mature well dressed gent with the bowler and brolly (bit of a swinger, don’t you know – the brolly I mean) spies a rather spiffing looking chick on LinkedIn and it’s not just his hat that’s “bowled” over, what! So he pings this miss a missive and she gets all of a twitter, only not in a nice way, and before long he finds his name is mud and hers is in all the papers, alongside very much larger copies of the image that initiated the whole saga. Starring (though not for long) a city slicker (surely solicitor?) and a bar girl (surely barrister?) the whole thing seems blown out of all proportion. Still that’s social media for you. All’s fair in love and war, but in law it constitutes discrimination. So just behave yourself, you silly old man.

For more sensible comment about a completely unrelated story, please read The Secret Barrister, Sexism? Welcome to the Bar, love.

Plus all papers, everywhere, over the weekend. (Now let’s draw a line under it.)

___________________________________________________________________________________

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR. It does not necessarily represent any views of ICLR as an organisation.