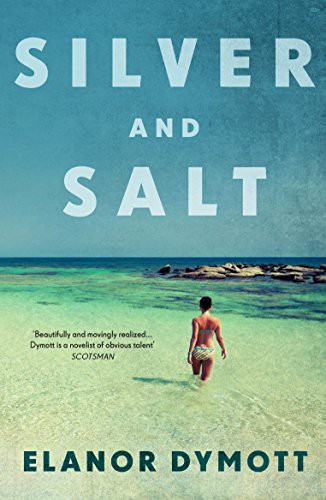

Silver and Salt: Elanor Dymott’s novel of photographic life – and death

Elanor Dymott used to work for ICLR as a law reporter. Then she became a novelist. Silver and Salt is her second book and makes excellent holiday reading for the long vacation, as Paul Magrath finds out.… Continue reading

Elanor Dymott’s novels are hard to pigeonhole in the convenient way the book trade’s publicists seem to want. Her first novel, Every Contact Leaves a Trace was a murder mystery that was far more about the buried emotional histories of its smart but damaged young characters than the forensic detection trail along which the narrative was suspended.

A mysterious death also lies at the shocking conclusion of her new book,

“Max is a famous photographer (portraits and photo-journalism), also a philanderer, selfish and quick-tempered. After his death in 2003, his daughters, Vinny and Ruthie, return to the family villa in Greece. For Ruthie, the younger sister, a photographer herself, it is her first visit since she cut off relations with her father 15 years ago, for reasons never explicitly spelled out. There is a family tragedy in the background. The girls’ French mother, Sophie, an opera singer who abandoned her career when Vinny was born, suffered a breakdown, originally provoked by Max’s infidelity, and became mad. Ruthie has inherited her instability. The girls were brought up principally — and lovingly — by their Aunt Beatrice, Max’s elder sister. We know from the first pages that the story will end badly; the question is how, in what form, and why?”

The narrative moves back and forth in time, alternating between Max’s family history and career in England and contemporary scenes in a villa in Greece where, following his death, his daughters tussle over his legacy. This layered structure enables the clues about the impending tragedy to be sewn into the fabric of the novel at intervals, maintaining the reader’s curiosity.

The characters aren’t often likeable but they are believable and, even when behaving badly, the sense of their being capable of redeeming themselves, is always there. Even the absent and arrogant Max is given to surprising acts of generosity and fun.

The dark room in which he and other members of the family find themselves is not just a feature of chemical photography; it can be read as a symbol of the neurosis and negative energy which afflicts them. Ruthie, in particular, is a victim of her father’s absence, coldness and emotional abuse. Having inherited her mother’s fragility of mind, she is increasingly distracted from reality and her view of things is not always reliable.

You could come up with other photographic connections; the word “negative”, the idea of something being “developed”, gradually emerging in the dish of darkroom chemicals, and then being “fixed” in time and place. The technical demands and paraphernalia of pre-digital photography are key to understanding the mechanics of a tragedy the true nature of which builds up only gradually over the course of the novel. The prose is itself almost photographic in its luminous clarity. The climax is shocking but, in the context of all that has gone before, has its own crazy kind of logic.

Elanor Dymott worked as a solicitor and then as a law reporter (at the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales (ICLR) which is how I came to know her) before going full time with her fiction writing. She also teaches writing.