Review: The Evolution of the Law Report

ICLR reporter and editor Susanne Rook reviews the current exhibition at Middle Temple library. … Continue reading

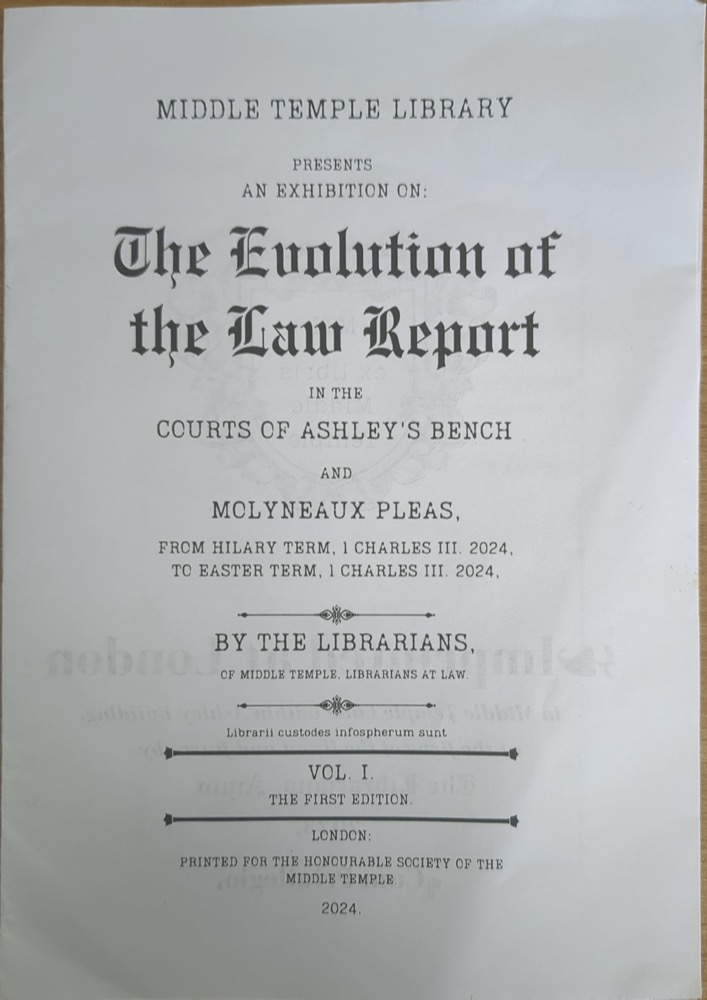

The current exhibition at Middle Temple Library, titled “The Evolution of the Law Report”, is well worth a visit and takes only a short time to walk around. The exhibition runs till the end of April, but you can take an online tour, at any time, via the Library’s website. Although the online tour doesn’t give you the hit of seeing the ancient documents in reality, with their strong historical connections, it does allow you to view the reports up close and in more detail than you can in person, and has added links to more information. Ideally, I would watch the online tour and then go to the exhibition in person, as you will have an idea of which documents you would like to see “in the flesh”.

The exhibition displays examples from the Library’s collections in glass cabinets, showing a time line of law reporting and highlighting the major developmental stages—from Plea Rolls, starting before 1189, to today’s digitisation and AI. Each stage contains a brief description of the content of the reports and the period in which they were produced. The information shows how the purpose and scope of the documents have changed from a mere record of decisions, aimed at preventing subsequent proceedings on the same subject matter, towards judicial opinion and reasoning.

It is striking to be able to see and read these ancient documents, even if most are written in Latin or Anglo-Norman French. The aged parchment or paper, with their stains and rips, adds to the feeling that you are looking back in time. I was particularly drawn to the private manuscripts, which were written in perfect, tiny handwriting, some with added notes in the margin.

You can make sense of the manuscripts written in English, despite the use of Olde English, many of the words and phrases are recognisable, as they were used up until the 1998 Woolf reforms, such as plaintiff, defendant, mandamus etc. Many of the manuscripts contain indexes and legal terms, as reflected in the modern law report.

It is very interesting to look at the links to the manuscripts in the virtual tour, when you can inspect the wording and handwriting in detail. The online tour includes a link to the index for Notes of cases heard at the Old Bailey, 1765-1969 constructed by a Library intern, Jack Alphey. Clicking on one of the entries—an indictment against Jack, Mary and Jeremiah Ryan for theft of, among other things, one pair of cotton stockings and one silk purse, takes you to the manuscript. It is fascinating reading the victim’s testimony: “I was born at Bengal … I came over with a tyger for Sir George Pigot , who was governor of Madrass, and attend upon it for him now.” It is interesting to read, in the “notes” section of the index, that the victim, John Morgan, declared he was “a Mahometan” and thus would only swear on the Quran. There followed a long disagreement over whether the court could take a non-Christian oath. When in the library you can scan a QR code which takes you to a PDF of a blog post written by Jack Alphey about his experience of reading through and digitally cataloguing 18th century manuscripts in the Library.

The importance of the local area around Middle Temple is ever-present in the exhibits. For example, with the arrival of the printing press in the 15th century, some of the manuscripts were printed by Richard Tottel (died 1594), a legal publisher who had a shop on Fleet Street at Temple Bar. One of his publications exhibited is a volume of Dyer’s Cases, or Ascuns Novel Cases, which was from the original bequest by Middle Templar and founder of the Library, Robert Ashley. Again it is intriguing to see the various “anonymous contemporary marginalia” and underlining and imagine a legal scholar pouring over the documents over 460 years ago!

Most law students are aware of the more well known Nominate Reports, which refer to lots of different series of law reports from the 16th century up to 1865. As referenced in the online tour, the Library says: “The nominates sit on the open shelves of Middle Temple Library. Although hundreds of years old, reports from this time are still often still utilised in cases today.” The various series are named after the law reporter who had written them, the most famous being the “Big Wigs”: Coke (1552-1634), Dyer (1510-1582) and Plowden (1518-1585): “Their collections of reports were not only seen as reliable but also exerted an influence on law reporting of the future.”

When the exhibition turns to the modern type of law report, it is interesting to note the reasons why the legal profession wished for a more standardised system of law reporting, one being the increased quantity but poor quality of law reports caused by the huge increase in publishing in the mid-17th century. This problem has not gone away and the modern system of the online publication of nearly every judgment of the higher courts has caused similar concern in recent years.

The considerable change in law reporting that took place in 1865 with the birth of the ICLR is clearly referenced in the exhibition and it is gratifying to read that the ICLR Reports “remain the most authoritative law reports today”. As the exhibition comes to its close, digitisation is explained and the ICLR’s online service is mentioned. When discussing online subscription-based law report services, it is pointed out how expensive they are for the customer, highlighting a need for free access. It is a shame that ICLR’s free WLR Daily reports are not mentioned here (or indeed the reasonableness of our monthly single user pricing).

I would definitely recommend the exhibition particularly if you are interested in the history of the English Legal System. Quoting one of my colleagues, it is “touching” to be able to look through this small window into our past.

Featured image (top) depicting proceedings in an Inn of Court, is from the title page of the Misteries of Clerkshipp by George Billinghurst (1674).