Judicial reflections from the apex court

Since retiring from the Supreme Court in 2018, Lord Sumption’s public profile has increased still further, first with his delivery of the Reith Lectures in 2019 and more recently as a public commentator on law and politics, most notably for his principled opposition to the coronavirus lockdown. We review his latest book and another which celebrates his contribution to the case law of the Supreme Court, alongside some reflections on the role of the court by its former President, Lord Neuberger.… Continue reading

Before his almost mystical assumption into the celestial hierarchy of the UK Supreme Court, without first doing penance on the High Court or Court of Appeal benches, Jonathan Sumption QC was something of a legend at the Bar: mildly eccentric, majorly successful. As Lord Sumption, he has achieved a different sort of fame since retiring from the Bench, as a public commentator on the interface between law and politics. He has also remained, throughout his legal career, the medieval historian as which he began. He is therefore not only someone well worth reading, but also an interesting subject to write about, though few who do so can match the dash and verve of his writing style.

As an advocate, he had a winning way with sentences of impregnable logic, which he delivered in an emphatic, animated, almost bodily manner. His preparation was legendary, his focus intense. Having watched him in action, it was hard not to be impressed, if not intimidated. As a historian, he must sometimes have admitted to uncertainty; as an advocate, he never would. Something of this adversarial certainty was carried forward into his approach as a judge, unafraid to challenge the accepted wisdom of even the most widely followed precedents.

Meaning and intention in contract law

An example of this was his attitude to the interpretation of contracts, where he challenged a trend expressed in a series of cases in which the leading judgments had been given by Lord Hoffmann in the House of Lords (whose Appellate Committee was the predecessor of the Supreme Court). Broadly speaking, these precedents approached the construction of the wording of disputed provisions in contracts and other instruments by reference to evidence of what those drafting the document intended or could be inferred to have intended at the time, rather than solely by reference to the generally understood meaning of the words themselves as viewed in their context.

Lord Sumption set out his opposition to the established approach in an essay in the Supreme Court Yearbook vol 8 (2016-17) which is reproduced in his own latest book, a collection of essays entitled Law in a Time of Crisis (Profile Books). In “A Question of Taste: The Supreme Court and the Interpretation of Contracts”, Sumption writes that

“rather more than thirty years ago, the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords embarked upon an ambitious attempt to free the interpretation of contracts from the shackles of language and replace them with some broader notion of intention. These attempts have for the most part been associated with the towering figure of Lord Hoffmann.”

Note how, by using the description “towering” of Lord Hoffmann, the author casts himself in the role of David against Goliath. We are witnessing an act of judicial statue-toppling. A jurisprudential culture war. Sorry. Back to the narrative:

“More recently, however, the Supreme Court has begun to withdraw from the more advanced positions seized during the Hoffmann offensive…”

Another rhetorical device, you see, presenting one of the key players in the battle as its official historian. Well, they do say history is always written by the victors.

“… to what I see as a more defensible position.”

Still with the military historical analogy. (We might be listening to Tristram Shandy’s Uncle Toby modelling the fortifications from the battle in which he got his famous wound.)

By going on to describe the Hoffmann approach as “The House of Lords’ flight from language” (though he later acknowledges that it had its roots in earlier judgments, eg by Lord Diplock) Sumption widens the diagnosis from Lord Hoffmann to the House of Lords itself, thereby insinuating that the Supreme Court is in some way a better source of authority.

Lord Hoffman, in an essay entitled “Language and Lawyers” (2018) 134 LQR 553, was having none of this. He criticises Lord Sumption’s view as a form of “nostalgia” for the stricter approach of a bygone age, takes issue with Lord Sumption’s characterisation of his own approach, and pleads in conclusion:

“… let us not go back to the dark ages of word magic, of irrebuttable presumptions by which the intentions of a user of language are stretched, truncated or otherwise mangled to give effect to the ‘admissible’, ‘strict and proper’, ‘natural and ordinary’ or ‘autonomous’ meanings of words, even when it is obvious that it was not the meaning the author, actual or notional, could have intended.”

Both essays are well worth reading, and their difference of approach is also the subject of an essay by Professor Ewan McKendrick in Challenging Private Law: Lord Sumption on the Supreme Court (Hart). This book, edited by William Day and Professor Sarah Worthington, is essentially a celebration of Lord Sumption’s contribution to the case law of the apex court in various different, mainly commercial law, areas.

Ending the life of PI

Another such area is the topical matter of personal injuries litigation, aspects of which are the subject of somewhat dithering legislative reform in the face of some quite fierce lobbying from interested factions. In a lecture delivered into the lion’s den of the Personal Injuries Bar Association in 2017, entitled “Abolishing Personal Injuries Law: a project”, Lord Sumption revisited and recharged the late Professor Atiyah’s criticism of the “big business” of PI litigation, arguing instead that a system of compensation for injury based on the victim’s need rather than another person’s fault would cost the nation far less. He was sceptical about the value of finding fault as a way of deterring negligent behaviour and suggested that as a mechanism for compensating the victim, “the law of tort is an extraordinarily clumsy and inefficient way of dealing with serious cases of personal injury”.

Another such area is the topical matter of personal injuries litigation, aspects of which are the subject of somewhat dithering legislative reform in the face of some quite fierce lobbying from interested factions. In a lecture delivered into the lion’s den of the Personal Injuries Bar Association in 2017, entitled “Abolishing Personal Injuries Law: a project”, Lord Sumption revisited and recharged the late Professor Atiyah’s criticism of the “big business” of PI litigation, arguing instead that a system of compensation for injury based on the victim’s need rather than another person’s fault would cost the nation far less. He was sceptical about the value of finding fault as a way of deterring negligent behaviour and suggested that as a mechanism for compensating the victim, “the law of tort is an extraordinarily clumsy and inefficient way of dealing with serious cases of personal injury”.

That speech is also reprinted in Law in a Time of Crisis, and is the subject of another essay in Challenging Private Law, in which Nicholas J McBride considers and challenges Lord Sumption’s critique. He does not agree that the alternative (or addition) of a no-fault compensation scheme, eg for victims of negligence in the NHS, would save money overall. The expense of administering any such system “would far exceed any administrative savings from the withering away of claims of negligence against the NHS.” (But, to turn this round, are we saying that victims of illness would be more efficiently served by a system of medical insurance and diagnostic litigation than by the NHS as it is? Part of Lord Sumption’s point is surely the hit-and-miss inconsistency of the remedies provided through fault-based compensation.)

The role of the courts

What is perhaps more surprising in Lord Sumption’s proposal is that it involves very substantial government interference into what is otherwise largely a matter of private law. He even uses the word “socialisation” to describe the process. This is surprising because elsewhere Lord Sumption has strongly criticised government intervention into the private sphere, most notably over the imposition of restrictions on personal liberty during the coronavirus pandemic. His views on this are set out in a chapter of Law in a Time of Crisis entitled “Government by Decree: Covid-19 and the British Constitution”, where he complains that “For three months it placed everybody under a form of house arrest” and says “history will look back on the measures taken to contain [the pandemic] as a monument to collective hysteria and government folly”. Yet in general his views do tend to favour law being made by parliament (as the Coronavirus Act 2020 duly, if somewhat hastily, was), at least in preference over its being made by the courts.

The tension between the government, the legislature and the courts, which occupied much of Lord Sumption’s Reith Lecture series, was one of the subjects of a series of “dialogues on the subject of power” held by the Westminster Institute in 2015 and 2016. One of these, now the subject of a book, was The Power of Judges (Haus Publishing), in which Lord Neuberger, former President of the Supreme Court, responds to questions by Peter Riddell, former director of the Institute for Government. It’s rather an excellent little book, not least for the introduction by Claire Foster-Gilbert which neatly summarises the constitutional background to the doctrine of the separation of powers.

Since retiring, Lord Neuberger has generally confined his public pronouncements to matters concerning the judiciary and the law, and while his views on topics such as judicial diversity may be fairly progressive, he has not courted controversy in quite the way Lord Sumption seems to have done. Sumption’s views on judicial diversity, informed as they may be by his prior involvement in the Judicial Appointments Commission, seem distinctly old-fashioned, favouring a narrow view of what constitutes merit, which he says is mandated by the rules. His now notorious essay “Home Truths about Judicial Diversity”, suggesting it might take up to half a century for the bench to achieve gender equality, is republished in his book. Neuberger seems to take a broader view of merit, saying that

“when deciding cases it is important for judges to bring to the table – or, rather the bench – as many different views as possible, as many different experiences as possible. And that is only achievable if you have a properly diverse judiciary.”

On the separation of powers, their views are much the same, though they may not express them in quite the same way. Lord Neuberger points out that if judges have become more “proactive” over the past 50 years,

“that is largely because Parliament has conferred those powers on us, and the fact remains that if we do something Parliament doesn’t like … Parliament can overrule us. So the idea of the unelected judges overruling or contradicting the elected members of the House of Commons is false, because even if we decide that a statute means what Parliament didn’t intend it to mean, which does happen, Parliament can always change the law.”

Lord Sumption said much the same in his Reith lectures, while pointing out that the courts have sometimes had to step in where Parliament, or the Government, has failed to act. Both former justices take the view that the UK Supreme Court is not, currently, a constitutional court in the traditional sense, capable of striking down legislation. But Sumption, in one of his essays on Brexit, thinks the court “has assumed an increasingly constitutional role”.

All these books are interesting, but what distinguishes Lord Sumption as a writer is, perhaps, his retention of that sense of adversariality, of making an argument. Without reading his history books, it is hard to say whether they are adversarial or judgmental – perhaps the most obvious word for a reviewer to reach for would be magisterial. But what has become clear since his retirement from the Supreme Court is that he likes the sound of his own opinions, is happy to be paid to voice them, and that, with his columns in The Times and readiness to engage with the media, he has become a sort of media darling. He should watch out. That may be the first step towards becoming a national treasure.

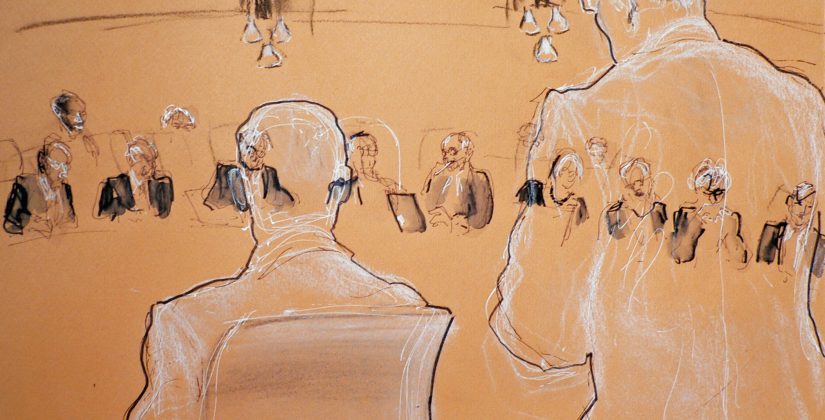

A note about the illustrations

The illustrations used in this post are by Isobel Williams, who regularly draws at the UK Supreme Court and is the author of The Supreme Court: A guide for bears. The main illustration is from the hearing of Bank Mellat v HM Treasury (No 2) [2013] UKSC 39; [2014] AC 700 in which Lord Sumption was one of an enlarged bench of nine justice. The other is a portrait drawn from a distance during another case hearing. Her illustrations are often used on book covers, including that for Challenging Private Law.

Her own latest book is Catullus: Shibari Carmina, a collection of translations of the Roman poet Catullus illustrated with drawings of Japanese rope bondage (shibari). She explains about her drawing techniques in a recent video: Roped to Catullus: Isobel Williams on Drawing Bondage.