Encounters with danger – the life of a frontline reporter

We review the memoir of veteran reporter and broadcaster Jon Snow, who appeared in the first of the ICLR Encounters earlier this year.… Continue reading

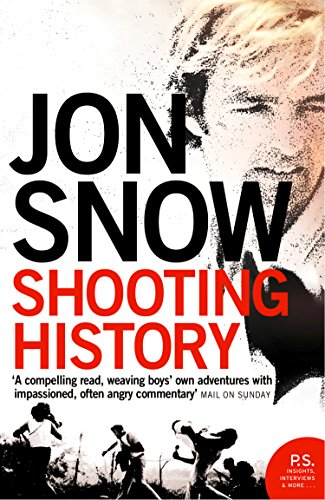

When Jon Snow appeared in the first of the ICLR Encounters earlier this year, to discuss “The truth, the whole truth, or a version of the truth…” with novelist and former law reporter Elanor Dymott, she described his memoir Shooting History as presenting a very “muscular” pursuit of journalistic truth. But if you read the book, the most surprising thing about it is the fact that its author is still around to tell the tale. The brushes with danger (including being shot at) come on almost every page.

When Jon Snow appeared in the first of the ICLR Encounters earlier this year, to discuss “The truth, the whole truth, or a version of the truth…” with novelist and former law reporter Elanor Dymott, she described his memoir Shooting History as presenting a very “muscular” pursuit of journalistic truth. But if you read the book, the most surprising thing about it is the fact that its author is still around to tell the tale. The brushes with danger (including being shot at) come on almost every page.

On one occasion, reporting in Uganda (a country he fell in love with while working as a volunteer teacher in his student days), he finds himself couped up in a tiny aeroplane with that country’s infamous and unpredictable dictator, “His Excellency Life President” Idi Amin, who slumbered sterterously with a gun hanging from his belt. It would have been so easy for Snow to take the gun off Amin and use it to blow a hole through the dictator’s head, thus ending a good measure of his beloved Uganda’s troubles. But the hole could have extended through the aircraft, they might all have been killed, and that would have been the end of the author’s promising career.

Though self avowed cowardice played a part on that occasion, Snow’s objective professionalism is never in doubt. The title “Shooting History” refers to the filming of events, rather than any active participation in their development. Nevertheless, time and time again Snow finds himself on the front line of conflicts in which he witnesses history unfolding before his eyes.

One of the scariest confrontations comes near the end of the book, and in the most unlikely of places. He is lying in a hotel room, naked in bed, when the door bursts open and a number of armed policemen surround him. A blanket is wrapped round him and he is marched off to a cell, where he spends the next few hours trying in vain to be given the chance to make a phone call. No one will tell him why he has been detained. Eventually, he is allowed to make a phone call, summons help, and is released.

The place? Some fly blown third world dictatorship? Actually, it was Switzerland. And the reason was, he hadn’t paid a speeding fine on a previous visit to the country.

As well as being a memoir of the life of a front line journalist, this book offers a survey (admittedly rather a partial one) of what is repeatedly referred to as the “new world disorder” which has followed the conclusion of the Cold War and (in Britain) the breakup of empire. Time and again he shows how each “solution” to a problem — usually the result of blinkered self-interest on the part of Britian, the US or some other imperial power — simply leads to yet another problem for one of the weaker or “failed” states in the world

Snow grew up in the post-war period, and despite being the privately educated son of a bishop, a pillar of the establishment, he embraced the revolutionary idealism of the 1960s, foregoing a law degree from Liverpool University after being sent down for a year for participating in a student demonstration. He stumbled into journalism after working for a charity helping the drug addicted homeless in London. Yet time and time again it is journalism that proves the addictive drug for Snow, calling him away from his family to yet another encounter with danger.

Discussing versions of truth with Elanor Dymott in the first of the ICLR Enounters, Snow admitted that one of the hardest things about reporting front line news was not necessarily maintaining objectivity, though that was crucial: it was simply being able to find out what exactly was going on. What this book shows is that even if you manage to get hold of the facts, and work out what is going on, and present a report, you still have to get the footage safely back to the studio. That’s easier in the digital age than it was in the old days, and some of the best stories are of beating the competition, by hook or by crook, to get the story home. On one frustrating occasion, they do get the story home, only to find it wasn’t run, because in the absence of any competitive coverage (a “second source”) the studio editors couldn’t be sure it was actually right!

There are many “might have beens” in this book, but perhaps the most interesting for us is to wonder what might have happened if Jon Snow had not been rusticated for taking part in a student demonstration in 1969, and had completed his planned law degree. To judge from his spirited defence to an earlier charge of assaulting a police officer (during an anti-Apartheid march), including a demolition-job cross-examination of the officer concerned, one would expect him to have been a highly successful one. A thorn in the side of the powers that be, no doubt. As it is, the style of his interviewing often strays into almost forensic adversarialism. And the regard for truth and justice are the same. Long may it continue.

Keep an eye out for the next of the ICLR Encounters. For full details, check out our special Encounters website.