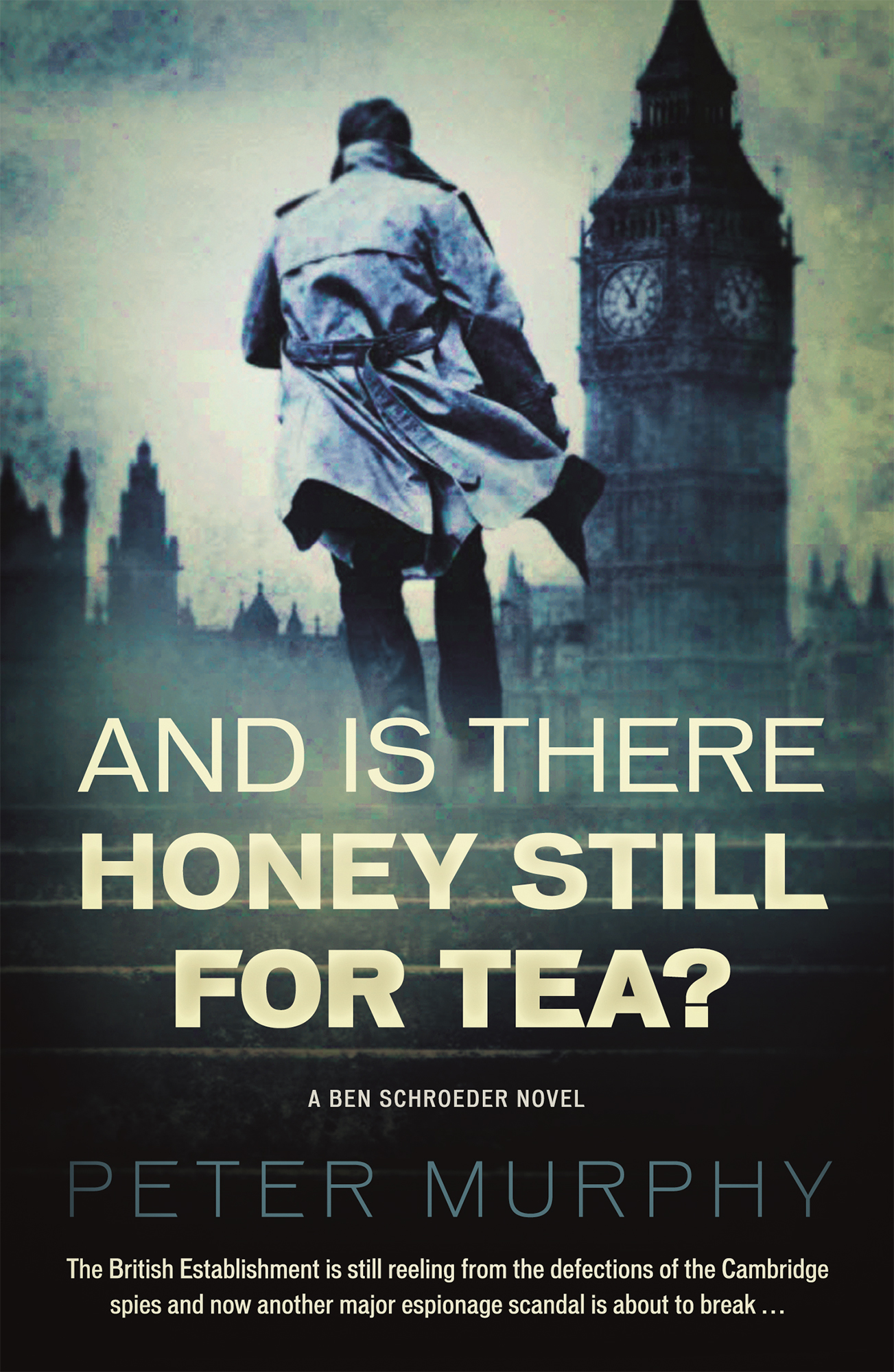

Chancery, chess and chicanery: “And is there Honey Still for Tea?” by Peter Murphy

Book review by Paul Magrath It is the mid-1960s and Ben Shroeder is a young barrister struggling to establish his career in the snobbish and prejudiced world of the English Bar. This is the third novel in a series which began with A Higher Duty, in which he served pupillage in the set of chambers… Continue reading

Book review by Paul Magrath

It is the mid-1960s and Ben Shroeder is a young barrister struggling to establish his career in the snobbish and prejudiced world of the English Bar. This is the third novel in a series which began with A Higher Duty, in which he served pupillage in the set of chambers which in the end was persuaded, against the odds, to accept him as a junior tenant; and continued with A Matter for the Jury, in which Schroeder, led by a brilliant but flawed QC, fought one of the last capital murder trials before hanging was abolished. Now comes a tale of treachery and conflicted loyalties in the twilight world of the Cambridge spies.

It is the mid-1960s and Ben Shroeder is a young barrister struggling to establish his career in the snobbish and prejudiced world of the English Bar. This is the third novel in a series which began with A Higher Duty, in which he served pupillage in the set of chambers which in the end was persuaded, against the odds, to accept him as a junior tenant; and continued with A Matter for the Jury, in which Schroeder, led by a brilliant but flawed QC, fought one of the last capital murder trials before hanging was abolished. Now comes a tale of treachery and conflicted loyalties in the twilight world of the Cambridge spies.

Today’s visitors to the cloistered world of the Inns of Court, with its stone buildings and collegiate quads, may find themselves comparing it most readily to the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge from which so many of its members seem to be drawn. That may be an anachronistic cliché these days, with our inclusiveness programmes and diversity agendas; but wind the clock back half a century to when the young Ben Shroeder joined the chambers of Bernard Wesley at 2 Wessex Buildings in Middle Temple, and the comparison would have made perfect sense. This was the age when “the Establishment” actually meant something; when those in positions of power and influence could pull strings and get things done, or covered up, in a way that nowadays, with our freedom of information requests and door-stepping press, one can hardly imagine. (Just such a pulling of strings and covering up of scandal, based in Cambridge, forms much of the subject matter of A Higher Duty.)

In this world of power, influence, and presumed entitlement no one thought to question the motives of those brilliant young men who, whilst studying at the aforementioned university of Cambridge, joined a secret society (the Apostles) one of whose tenets seems to have been that loyalty to each other and to their shared ideals should take precedence over any of the more routine bonds of family or patriotism. That was one way of looking at it. Another would be to say they became foreign agents, enemy spies, traitors. You may have heard of some of them: Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt. You may also know that others were suspected, though never conclusively revealed – a fifth, sixth, even seventh man. Their recruitment to the Soviet cause during the 1930s, at a time when the dominant threat seemed to be the fascism that had caused the Spanish Civil War and the nascent threat of Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, and would eventually lead to the Second World War (in which Soviet Russia was an ally), may in retrospect be both understandable and, to some degree, forgivable (at least until the miserable failure of the Soviet system and the absolute despotism of its leaders became obvious). But what may seem rather less forgivable is the laxness of the Foreign Office and the intelligence services in recruiting these moles and allowing them to flourish, under their very noses, largely on the basis that, as public school educated Cambridge scholars, they must have been “on our side”. (The so-called “Decent Chaps Fallacy”.)

Burgess and Maclean defected to Moscow in the early 1950s, having been tipped off by Philby; and Philby himself, having also been discovered, in 1961. Although Blunt was known about by 1964, his identity was kept secret (until 1979), partly to lull the Soviets and partly not to scare the public horses. But the idea that others might be involved was haunting the security services of our own country and, significantly, our main ally, the United States.

This is the setting, and the atmosphere of paranoia and suspicion, of And Is There Honey Still For Tea? in which an American academic, Francis Hollander, publishes in an academic journal an article accusing an English baronet, Sir James Digby QC, who is also a well-established Chancery Silk and a talented international chess player, of being yet another of these Soviet spies. Like Oscar Wilde before him, Digby feels he has no option, if he is to retain his good name, but to sue for libel. Ben Schroeder is part of his legal team, and although the burden is on Francis Hollander, as the defendant, to justify his defamatory statement about Digby, Schroeder must still investigate the claim on his own behalf and test the evidence which may be produced against his client.

Unusually, much of the story is told from Digby’s point of view, in a series of chapters which appear to form part of his memoirs, and provide a clue to the background of Hollander’s accusation. The key circumstance is that both men are brilliant chess players, though not in the same league as the Soviet grand masters who enjoy, to Digby’s chagrin, much better training and resources than are available in England. (The chess tournaments provide an opportunity for some tradecraft and, it is alleged, treachery.) Digby’s family history is also relevant, in particular his relationship with his elder brother, who also went to Cambridge, and volunteered to fight on the Republican (ie anti-fascist) side in the Spanish Civil War. What emerges is a psychological character study, rich in ambiguity.

The novel also explores questions of professional ethics and responsibility, as Schroeder finds himself having to engage in some fairly cloak and dagger manoeuvres to perform an assessment of the evidence against his client. But it turns out the greatest threat to his continuation of the career he loves might be the girl he loves, or rather the fact that she is a solicitor, which means their relationship breaches the strict “no touting for work” rule imposed by the governing bodies of his Inn. Readers of the earlier novels may remember Jess Farrar, with whom Ben became romantically involved in A Matter for the Jury. Now, in spite of every obstacle, their relationship blooms into something stronger than either of their careers.

This third outing for Schroeder is different in tone and style from its predecessor, but no less reliably gripping. There’s tradecraft of the John le Carre kind, but there’s also a steely authenticity in the legal scenes, born of Peter Murphy’s long involvement in the law, as a barrister, teacher, writer and, currently, judge. My only disappointment is that he only cites one law report (Duncan v Cammell Laird – on the public interest immunity against disclosure of sensitive information), and even then doesn’t give the full citation!

The full title and citation should be: Duncan v Cammell, Laird & Co Ltd [1942] AC 624, HL(E)