Dickens Did It First: Writing and the Law

Novelist Elanor Dymott explains how she was inspired to move from the law to fiction via law reporting for ICLR.… Continue reading

I once met a woman at a wedding, who unwittingly changed my life. At the time I was an unhappy lawyer who wanted to write fiction. I spent my days and nights assisting bankers and company directors and the owners of fleets of ships, aircraft or insurance conglomerates, to make vast amounts of money, then avoid getting sued for the way they’d made it. Writing was limited to contracts, litigious letters, and research memos.

The wedding was in one of London’s Inns of Court, near Temple tube. I was distracted by the improbably beautiful herbaceous beds when the woman was introduced. At the precise moment when she said she was a barrister-turned-law reporter, I was focusing on a bank of peonies, just to her left. Afterwards, going over the details of our conversation, three facts emerged: only qualified lawyers were eligible to work as law reporters; she kept court hours (10 am to 4 pm); and her holiday allowance (four times my own) was free from client interference.

The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales was founded in 1865 with a view to ironing out considerable wrinkles in the then state of law reporting. Because English common law works on a system of binding precedent, accurate and reliable law reports are essential: to argue on the basis of previous judicial decisions, you must know what those decisions were, and how they were reached.

Before 1865, the search for such a report would result more often in a miss than a hit. As Paul Magrath, the ICLR’s Head of Product Development and Online Content, explains in The Law Reports 1865–2015 Anniversary Edition, regular law reporting began in 1189. Authority for propositions was, as Magrath describes it, ‘decidedly … anecdotal.’ By the 16th century, individual reporters were publishing volumes of case reports under their own names. ‘Flanagan & Kelly’ was one of many duos who did so with a title suited to a comedy act.

The problem with those various reports, now referred to as ‘The Nominate Reports,’ was two-fold: variable coverage, and the frequency with which cases reported in more than one series appeared with different conclusions. The astringency of judicial commentary on these downsides makes for rich reading. As Lord Denman CJ said of Epinasse, whose six volumes date from 1793–1807, his reports were ‘never quoted without doubt and hesitation.’ And as Lord Holt exclaimed of volume 4 of the Modern Reports (1669–1732), ‘… [they] will make us appear to posterity for a parcel of blockheads!’

The ICLR met a need identified by an 1849 report of the Law Amendment Society who complained that ‘any barrister and bookseller who unite together with a view to notoriety or profit [can] add to the existing list of law reports.’ Even if the reports had been correct and by competent persons, they would have been ‘beyond the reach not only of the public, but of the great body of the profession.’

Today, by the Lord Chief Justice’s (Lord Judge) Practice Direction, if a case has been reported in one of the official series published by the ICLR, it must be cited and referred to in that version in court, instead of any other. ICLR reporters apply strict selection criteria, reporting only those cases which lay down a new principle of law, or change or clarify the existing law; not all decisions taken in a court of law set a precedent, however interesting they may be.

Shortly after that wedding meeting, I read an interview with Ian McEwan, advising anyone wanting to be a writer to get a job which required them to write every day. The deal was sealed. I applied, and wrote a sample report summary (called a ‘headnote’, in which the facts are set out and the points of law distilled), and said goodbye to the city.

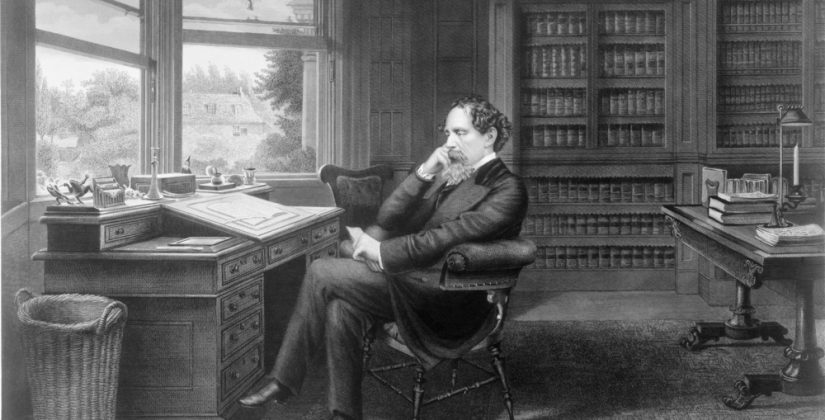

I spent my first weeks in the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand under the mistaken impression that I could count Charles Dickens among my forbears. It must have been something I overheard at lunch one day: the length of the tables in Middle Temple Hall made conversations like games of Chinese whispers. Heady with excitement at my escape from my brief career as a corporate lawyer, I enjoyed my misunderstanding. If Dickens did it first, I reasoned, then I must have made the right decision: becoming a writer was within the realms of possibility.

I found out much later that though there was once a series of law reports called ‘Dickens’ Reports,’ it had nothing whatever to do with the novelist (its two volumes cover the period 1559–1792). Charles Dickens the novelist, after a brief period as a clerk in a solicitors’ firm, reinvented himself as a journalist in the Doctors’ Commons, not far from St Paul’s Cathedral. As he has David describe it in David Copperfield, ‘Altogether, I have never, on any occasion, made one at such a cosey, dosey, old-fashioned, time-forgotten, sleepy-headed little family-party in all my life…’ He was a reporter of the news variety, not a law reporter, covering the Doctors’ Commons and Parliament, where he was famous for the speed of his self-taught shorthand.

Although we can be sure that Dickens never wrote an actual law report, then, what’s equally certain is that he couldn’t have written the novels he did without that first-hand experience of being in and around the workings of the British legal system. As Magrath observes, while the Circumlocution Office in Little Dorrit may be a satirical fantasy, the Lord Chancellor’s court in Bleak House is depressingly rooted in a reality familiar to Dickens.

Today, the path from lawyer to novelist is a well-trodden one. Three things in particular from my decade of law reporting shaped my version of the journey.

Being closely edited.

For the official Law Reports, my report would be sub-edited and on occasions, the headnote recast. A copy was then sent to the judge, for her approval or otherwise. I’d take on all those comments, then the whole report would be approved, or otherwise, by the editor of the Law Reports. Only then would it go to print.

My editors were careful craftspeople, and generous with it. Each of them was an expert in expressing, simply and clearly, day in day out, the often complex stories behind the judgements of the British judiciary.

The Times Law Reports were swifter (a report could appear in the paper the following day) but none the less careful: the TLRs are written only by ICLR reporters, and are frequently cited in court. My draft would be delivered as soon as possible after court closed, and the editor, Iain Sutherland, would come back to me with any queries. For my first report, I handed in the judgment as well.

‘Why are you giving me that?’ Iain asked.

‘For you to check I’ve got it right.’

‘No need. The judge will read the newspaper, and phone if it’s wrong.’

That trust in my ability was instrumental in making me able to write. I realised that he was saying I was as well qualified as anyone to construe the points of law. The rest came bit by bit: however short my reports, he always made them shorter. Years later, Iain told me he’d learned his trade not only as a barrister, but also as a news reporter. ‘Who, what, when, where, why, and what happened next. That’s all you need.’ Though I’ve yet to achieve his succinctness, it’s a lesson I use today when writing a novel.

Exploding with stories.

I wrote my first short story when I was a reporter in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court, sometimes covering up to fifty courts a day. I needed to write the stories down in a looser, freer form than that licensed by my job, fearing I might otherwise spontaneously combust, in the manner of Mr Krook.

It takes two.

It’s said in defence of the UK’s adversarial common law system that, ‘Argued law is good law.’ I spent every day watching first one side, then the other, tell the same story differently, and critique each other’s version. Imagine watching something like Rashomon, every day for ten years, and you get the picture. The judge, it sometimes seemed, was there to decide whose story was the best. And the truth, as I so often discovered, really is stranger than fiction.

I’ve a daydream of one day writing my own Bleak House. I’ve got boxes of papers, notes, timelines, characters, and a handful of chapters. For now I’m sticking with small novels, learning my trade. Dickens, then, if not exactly a predecessor-colleague, is an inspiration. Stories of the novelist were everywhere at the law courts. Canvassing my former ICLR editors for the purposes of this article, I was entertained by one anecdote in particular. Nicholas Mercer remembered a supervisor from his barrister days (at the bar, they are called ‘pupil masters’) who claimed that his room had once been occupied by Charles Dickens. As Mercer pointed out to me, since his chambers stood on the site of a building that had been razed to the ground by the Luftwaffe, the claim was widely regard as an out and out fib. That pupil master, like the rest of us, wanted a little piece of that storyteller of storytellers, without much minding if the story were true.