Miller: hearing documents and understanding a case in the Supreme Court

The way the cases have been presented in the Supreme Court this week in the appeals against R (Miller & Anor) v The Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2016] EWHC 2768 (Admin) ; [2016] WLR(D) 564 has shown how much court cases can be opened up for the understanding of interested members of the public and… Continue reading

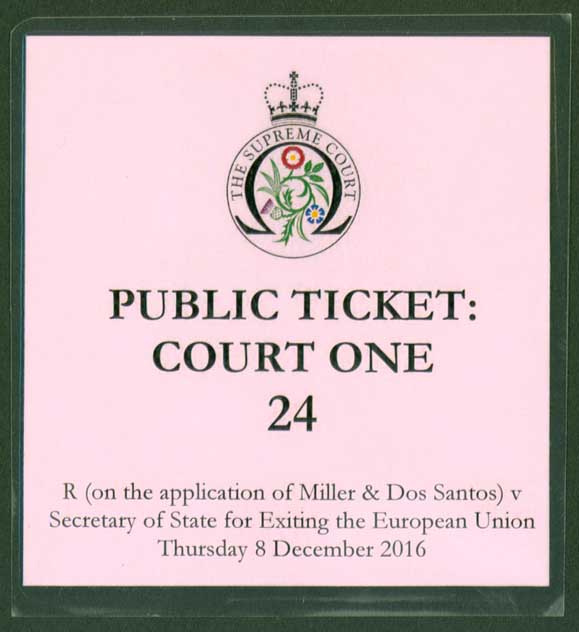

The way the cases have been presented in the Supreme Court this week in the appeals against R (Miller & Anor) v The Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2016] EWHC 2768 (Admin) ; [2016] WLR(D) 564 has shown how much court cases can be opened up for the understanding of interested members of the public and press.

In this article David Burrows looks at the extent to which the law permits this; at what the arrangements were to help with the understanding of the Miller case; and at how effective these arrangements were. It will then look briefly at what the present legal position is; and, finally, consider what could be done to ensure as much understanding of a case for press and non-parties.

In this article David Burrows looks at the extent to which the law permits this; at what the arrangements were to help with the understanding of the Miller case; and at how effective these arrangements were. It will then look briefly at what the present legal position is; and, finally, consider what could be done to ensure as much understanding of a case for press and non-parties.

It builds on what he said in his earlier post, Family law no island (2): Release of family courts hearing documents in relation to transparency in the family courts, and how it could assist everyone, especially the press as “watchdog for the public”, to have access, as far as possible (allowing for the need for privacy and confidentiality in some cases), to the same information as the judge.

Arrangements for documents in Miller

In Miller, both in the Supreme Court and in the earlier High Court hearing, the parties’ skeleton arguments were published and could be accessed online. For example in the Supreme Court these were at

https://www.supremecourt.uk/news/article-50-brexit-appeal.html

amongst what the court office described as a ‘range of information and updates’ on the case. As far as I could see what was provided was limited – as the website explained it – to the “written arguments (or “cases”) of the parties and each of the interveners”. After each day, a full transcript was made available; and, at the site above at the end of the hearing on 8 December, a short next- steps-by-the-court background note for lay people appeared on the Supreme Court site.

All this was truly most helpful for an understanding of the case. Significantly, perhaps, what was published, and how, mostly depended on the good will of the court and of the parties. This was a case which was as sensitive politically, legally and constitutionally as could be imagined. It cannot always be thus, I am sure. A question which this article will touch on will be the extent to which such openness and helpfulness can be achieved in some more important cases in the future.

Thoughts of a legally trained observer

So as an observer – legally trained, but no expert in public law, observer – how did I get on as one who wanted to understand the proceedings? It was the “understanding of the proceedings”, so that transparency of the court and its process could be fully effective, which was my criterion for passing on hearings documents in my “transparency” article.

These documents, presented in the language of the barristers acting in the case, gave the reader, whether lawyer or lay-person, a summary of what they would be saying to the court. However, once you got into the hearing, unless you knew the subject (which included constitutional, administrative and European law) well, you were at a disadvantage. Statutes were described as ‘ambulatory’. Technical or coined-for-this-case terms were frequent: ‘the Great Repeal Bill’ (not the title of anything – yet), ‘dualism’ and ‘clamp’ on prerogative rights, ‘Sewel’ (ie Sewel Convention), ‘the 1972 Act’ and ‘Henry VIII clause’. As so often in discussions between people familiar with a subject, initials were in frequent use: ECA, TEU etc. Some terms may have been explained when first mentioned, perhaps; but by the second day and afterwards a glossary of terms and abbreviations – which could perhaps have been developed on-line – would have been most helpful.

More particularly, lawyers tend to talk about a case by one name, where its full name is much longer; and this name – especially in administrative law – is often not by the first name in the title of the case. For one who does not know all the leading cases in the subject area, it is not possible to track down the case referred to, even if you happen to have an administrative law text book with well set out case tables to hand. For example:

- ‘Bancoult No 2’ refers to R (on the Application of Bancoult) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2008] UKHL 61 ; [2009] AC 453, HL(E).

- ‘De Keyser’ is Attorney-General v De Keyser’s Royal Hotel [1920] AC 508, HL(E).

- ‘Morgan Grenfell’ is R v Special Commissioner and anor, ex parte Morgan Grenfell & Co Ltd [2002] UKHL 21; [2003] 1 AC 563, HL(E).

- ‘The Public Law Project case’ is R (The Public Law Project) v Lord Chancellor [2016] UKSC 39; [2016] 3 WLR 387, SC(E).

- ‘Robinson’, a Northern Ireland case, is Robinson v Secretary of State for Northern Ireland [2002] UKHL 32, [2002] NI 390, HL(NI).

- ‘Shindler’ is Shindler v Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster [2016] EWCA Civ 469 [2016] 3 WLR 1196, CA.

The law and the release of hearing documents

Anyone who advocates release of hearing documents – and perhaps of still further information generally about court hearings – is in good judicial company, including Lord Scarman, Lord Bingham and Toulson LJ (later Lord Toulson: he retired from the Supreme Court shortly before the Miller hearing). All of them take as their starting point in different ways the assertion of the “open court principle” by Jeremy Bentham:

Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself while trying under trial.”

Toulson LJ in the Court of Appeal discussed the principle of the release of hearing documents in R (Guardian News and Media Ltd) v City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court (Article 19 intervening) [2012] EWCA Civ 420; [2013] QB 618; which concerned permission to the Guardian – after the hearing – to see documents in an extradition case. Toulson LJ referred to Lord Scarman, whom he described as “a thinker ahead of his time”, who had said of hearing documents, in Home Office v Harman [1983] 1 AC 280 at 316, that a judge needed to be concerned:

“… to ensure that justice not only is done but is seen to be done in his court. And this is the fundamental reason for the rule of the common law, recognised by this House in Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417, that trials are to be conducted in public. … there is also another important public interest involved in justice done openly, namely, that the evidence and argument should be publicly known, so that society may judge for itself the quality of justice administered in its name, and whether the law requires modification…”

Lord Bingham CJ followed up the point in SmithKlineBeecham Biologicals SA v Connaught Laboratories Inc [1999] EWCA Civ 1781; [1999] 4 All ER 498 at 511–512:

Since the date when Lord Scarman expressed doubt in Home Office v Harman as to whether expedition would always be consistent with open justice, the practices of counsel preparing skeleton arguments, chronologies and reading guides, and judges pre-reading documents (including witness statements) out of court, have become much more common. These methods of saving time in court are now not merely permitted, but are positively required, by practice directions. The result is that a case may be heard in such a way that even an intelligent and well-informed member of the public, present throughout every hearing in open court, would be unable to obtain a full understanding of the documentary evidence and the arguments on which the case was to be decided…”

This article’s concern – like that of Lord Bingham – is with their understanding of the case of the press and other non-parties as the case is happening in court. Modern procedure requires of parties that so much of a case is dealt with in documents read only by the parties (and their advocates) and the judge. This goes also for witness statements, expert reports and pleadings (at the outset of a case), as well as for skeleton arguments, position statements and other documents prepared for the final hearing (and mostly available in the Supreme Court in Miller).

Documents for an “understanding” of the case

So what can be done to provide to those attending court (or permitted to do so in private law cases) sufficient documents to comply with Lord Bingham’s criterion: to enable them (including someone like me in the Miller case) “to obtain a full understanding of the documentary evidence and the arguments on which the case” proceeds?

Anything said on this subject for private (especially family) proceedings must imply that released documents are anonymised and that any such release, in children cases, is fully sensitive to concerns of “jig-saw” identification of children and their families from law reports and other information which comes out from court proceedings. If documents are released for understanding of a case then anonymisation – for example in witnesses’ and other statements – will have to be imposed at the outset, perhaps by appropriate case management, so that a dramatis personae is developed from the outset of a case and initials – or false names – given to parties, witnesses and other private individuals involved. For it must surely be the case that one of the biggest gaps in a non-parties’ understanding a case is that most facts on which it is based will be in statements which are read only by the judge and the parties and their lawyers.

Hearings documents and rules reform

A few thoughts on how this might all work follow:

- Court rules will be needed finally to put into place what is to happen so that information about open court hearings is fully available to anyone who wants to understand a case.

- Court rules will include directions for anonymisation of documents filed in cases heard in private (mostly, but not exclusively, family cases: see cases covered by Civil Procedure Rules 1998 r 39.2 which defines civil proceedings which can be held in private).

- The list of hearing documents must be defined. The criterion for definition is: what would a non-party need to read to understand a court hearing. The list is likely to include: claim documents and witness statements; experts and other court ordered reports; interim court orders; and skeleton arguments. It is likely that with experience the list can be trimmed.

- Before the hearing a list of abbreviations, case name abbreviations and a glossary of unusual terms will be needed with final skeleton arguments. Eventually advocates, who do not already do so, will get used to summarising the issues in the case and their recommended disposal in the first few paragraphs of their skele.

- A list of cases with links to on-line versions where available; and – this may be controversial – a summary of the facts and findings in all important cases (where a head-note is not already available in a report published on-line) will be needed; and this summary must please be at a layperson’s level of understanding.

Whatever is required to make cases understandable will have resources implications: either for the Ministry of Justice, or for the costs of the parties, or both. This must be born in mind; but given the requirements in the common law and European Convention 1950 Art 6(1) for open court hearings, and that this must mean something for those who wish to attend, any resource questions must not be allowed to rule over the hearing documents scheme itself.

.

David Burrows is a solicitor advocate, trainer and writer. His book Evidence in Family Proceedings is published by LexisNexis/Family Law this month.

He writes a blog at DB Family Law