Review: Peep Show by Kate Summerscale; Inside 10 Rillington Place by Peter Thorley

Two books about a notorious multiple murder case that prompted public debate about the death penalty and continues to fascinate true crime historians.… Continue reading about Review: Peep Show by Kate Summerscale; Inside 10 Rillington Place by Peter Thorley

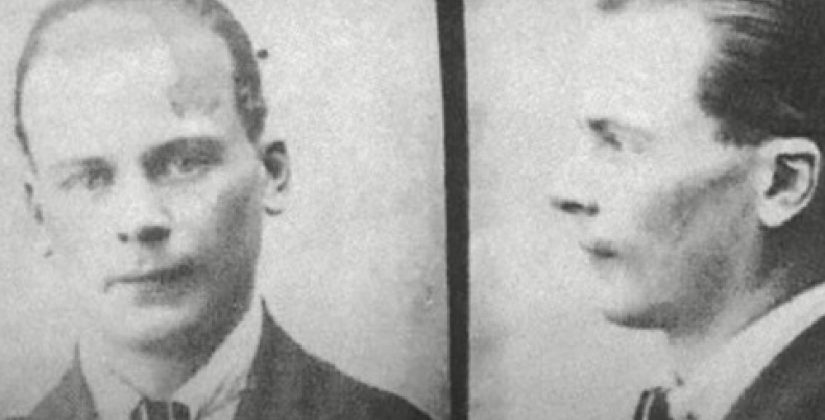

The murders at 10 Rillington Place continue to fascinate the true crime brigade and horrify the reading public more than 70 years after their discovery — not least because of the spine-freezing realisation that they were committed in an ordinary house by an ordinary looking man whom one might have passed in the street without a second glance.

John Reginald Halliday Christie, known as “Reg”, confessed to having killed at least seven women, including his own wife, in the notorious house in a dingy little side street in North Kensington where he lived from 1937 until 1953. He may also have killed the infant child of one of his other victims — a crime for which another man was hanged, in part on the basis of Christie’s own evidence.

The murders were only discovered when, after he had left the property, a number of bodies were found concealed in various parts of the rooms he had occupied on the ground floor of the house or in its tiny back garden. His wife’s remains were found under the floorboards in the front room; three other women’s corpses were found in a blocked-up alcove in the kitchen; the remains of two more were found buried in the garden; and two more, a mother and child, had been found concealed in the outside washhouse, in an earlier investigation, in which Christie had given evidence against the tenant of another flat in the property.

That other tenant was Timothy Evans, who confessed to having “done away with” his wife and child, and was convicted and hanged for the child’s murder in 1950. He had changed his story several times, and accused Christie of having committed the murders, but his reputation as a braggart and a liar devalued his testimony, while Christie gave evidence with the quiet respectability of someone who had served on the front in the 1914-18 war (when he’d been severely injured in a gas attack) and as a policeman in the 1939-45 war. (The criminal record he’d acquired between the two wars was not alluded to.)

Following Christie’s conviction for the murder of his own wife, and the discovery of other victims whom Christie had confessed to killing, it began to appear that Evans might not be guilty after all. If Christie had killed Evans’s wife Beryl as well as their baby daughter Geraldine, then Evans would have been wrongly hanged. Questions about a possible miscarriage of justice boosted the growing opposition to the death penalty, which Christie’s conviction and hanging did nothing to quell. Neither did two official inquiries, whose main purpose seemed to have been to shore up the correctness of the Evans conviction.

Kate Summerscale writes at the more serious and historical end of the true crime genre, and is probably best known for The Suspicions of Mr Whicher: or the Murder at Road Hill House, her meticulous and suspenseful account of a Victorian country house murder mystery dating from 1860. In Peep Show (published last year but now out in paperback) she approaches the Rillington Place murders through the eyes, initially, of a newspaper reporter, Harry Proctor, who not only covered both trials but also managed to befriend Christie, get his somewhat garbled and self-serving version of events for a “newspaper exclusive” after he was hanged, and arranged, through his newspaper the Sunday Pictorial, to pay for Christie’s defence. The case was a sensation and the press had a field day with the grisly details of the trial. Summerscale also views the case via the perspective of the court reporter, Fryn Tennyson Jesse, who covered both trials for the Notable British Trials series. But she also delves into the official records and uses material from a number of other sources, including the pathologists whose grim task was to examine the various corpses, and the psychiatrists who assessed the accused. It is, as you’d expect, a very thorough examination of the whole case, backed with sociological and historical context. It’s also a riveting read.

Although Evans was eventually pardoned, doubts remain over his guilt. Peter Thorley in his memoir provides his own perspective on the case. As the younger brother of Beryl, and the uncle of Geraldine, he recalls visiting 10 Rillington Place as a child, and speaks almost fondly of how Christie and his wife Ethel welcomed him into their kitchen and gave him sticky buns when he came to see his sister and her baby. He remembers Tim Evans by contrast as a violent drunkard and liar who continually threatened and assaulted his wife. He, at least, is in no doubt of Evans’s guilt, and thinks it likely that Evans’s initial confession to the police in Wales while on the run, after lying to everyone about where his wife and child were, was essentially reliable.

Both Proctor and Jesse appear to have had their doubts about the case, and Summerscale leaves us feeling rather less convinced of Evans’s innocence than some earlier books, notably Ludovic Kennedy’s 1961 classic, Ten Rillington Place, on which the classic 1971 film starring Richard Attenborough (as Christie) and John Hurt (as Evans) was based. But Thorley’s is not a complete answer. Much of it is based on conjecture and his own childhood impressions. He obviously feels strongly that Evans was a nasty piece of work, and was frustrated by the lack of support for his sister and niece from others in his own family, and his own inability to help, until it was too late. Although his book is not a complete vindication of the original verdict, it does weaken the case for Evans’s innocence. While Evans was officially pardoned in 1966, his conviction has never been set aside: in 2004 the Criminal Cases Review Commission declined to refer the case to the Court of Appeal, and the High Court refused judicial review (sought by his half-sister) of that decision: Westlake (Mary) v Criminal Cases Review Commission [2004] EWHC 2779 (Admin), DC.

Readers will have to make up their own mind as to the relative guilt of both men. For my part, a more interesting mystery is how much Ethel Christie knew about her husband’s proclivities, and eventually about his crimes. And was her dawning knowledge, or perhaps some articulation of her doubts, or a refusal to go on ignoring things, what prompted Christie to murder her? Previous accounts of the story have presented Ethel as either another victim or a timidly supportive wife; but Summerscale includes material about what Ethel had been doing in the years when she and Christie had been living apart, some of them spent by Christie in prison for earlier (mainly theft) offences. While staying in Sheffield with her sister, Ethel met another man, called Vaughan Brindley, with whom she had a longstanding affair and nearly married. But they fell out over his fears that she could not have children. All this not only points to the very different life Ethel might have had, but also raises questions about her character and motives for getting back together with the man who would ultimately destroy her.

Another difference Summerscale brings to her retelling of the case is her treatment of the other women victims of Christie’s disgusting depredations. Previous treatments — perhaps most offensively the 1970 play Christie in Love by Howard Brenton — have tended to characterise them simply as prostitutes and give them little depth or background as characters, let alone agency in their own narratives. One of the better developments of recent true crime writing has been a willingness to present victims as rounded human beings, where possible, the classic example being Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five, The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. One gets so fed up with the idea that “murderees” as Jesse called them, should be little more than corpse-candy in the narrative. Christie’s victims were lured into his lair on a variety of pretexts, and may have been desperate or naive, but to characterise them all as tipsy tarts or fallen women desperate for a back street abortion is reductive and offensive. Each of their deaths was ultimately a human tragedy. So I was glad to see that Summerscale devotes a decent amount of narrative to investigating their individual characters and histories.

The Rillington Place murders have been written about extensively before, and will no doubt continue to be. But for anyone not already familiar with the case, or wanting a comprehensive and objective modern perspective on the cases (Ludovic Kennedy’s treatment now seems both tendentious and dated), the Summerscale book is ideal. If, having read it, you still want more, or a more personal perspective, then the Thorley book is certainly an interesting addition.

The Peepshow, by Kate Summerscale (Bloomsbury)

Inside 10 Rillington Place: John Christie and me, the untold truth, by Peter Thorley (Mirror Books)

Featured image: Police mugshot of English serial killer John Reginald Halliday Christie, City of London Police photographic records (open source, via Picryl)