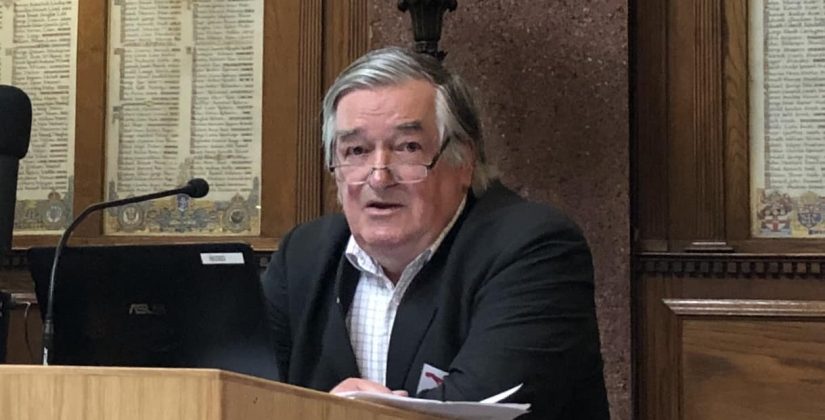

Sir James Munby

We have been saddened to learn of the recent death of Sir James Munby, a leading champion of open justice and law reform. … Continue reading about Sir James Munby

Few modern judges can have been as transformative of the courts over which they served as Sir James Munby was, during his term as President of the Family Division from 2013 to 2018.

But, much as he achieved, notably in opening the family justice system up to the scrutiny for which so many affected by it had long clamoured, he was often frustrated by his powerlessness in the face of institutional and governmental obstacles. Lack of funding, lack of support, and sometimes a fundamental lack of sympathy and compassion by faceless officialdom towards those at the mercy of the system, drove him to express himself with a warmth of purpose that is rare among the senior judiciary, but perhaps all the more remarkable for that reason.

Scrutiny can be uncomfortable, for those who work in the courts, and for many years the vulnerability of those involved in family cases provided a convenient excuse for maintaining their secrecy. Not any more. When Sir James took office, his immediate response was to issue a transparency manifesto, included in his speech to the The Annual Conference of The Society Of Editors in 2013:

“I am determined that the new Family Court should not be saddled, as the family courts are at present, with the charge that we are a system of secret and unaccountable justice.”

Shortly thereafter he issued practice guidance on the publication of judgments, urging judges in both the family courts and Court of Protection to publish on BAILII suitably anonymised judgments from private hearings, to enable the public to understand how the courts were dealing with cases in which the orders made were, as he had put in his Society of Editors speech, “amongst the most drastic that any judge in any jurisdiction is ever empowered to make”.

He gave as an example the state’s power, through the family courts, to make an order for the removal of a child from one family and their adoption by another, something that would affect all those involved for the rest of their lives.

But there were cases where the state’s unwillingness to act, or to provide the resources for others to act, could be just as drastic, even fatal. In re X (A Child) (No 3) [2017] EWHC 2036 (Fam); [2018] 1 FLR 1054, he expressed in eloquent terms his shame and frustration at the inability of the state to provide a secure clinical placement to meet the complex mental health needs of a vulnerable 17-year-old girl at a high risk of fatal self-harm, who had made many previous attempts on her own life, and who was about to be released from the secure unit where she’d been sent pursuant to a Detention and Training Order imposed by the Youth Court. He said, at paras 38-39:

“38. … For my own part, acutely conscious of my powerlessness – of my inability to do more for X – I feel shame and embarrassment; shame, as a human being, as a citizen and as an agent of the State, embarrassment as President of the Family Division, and, as such, Head of Family Justice, that I can do no more for X.

“39. If, when in eleven days’ time she is released … we, the system, society, the State, are unable to provide X with the supportive and safe placement she so desperately needs, and if, in consequence, she is enabled to make another attempt on her life, then I can only say, with bleak emphasis: we will have blood on our hands.”

Commenting on this judgment, and others like it, David Emmerson, a partner at Anthony Gold, wondered Is Sir James Munby the modern day Charles Dickens? Sir James was certainly well read, and not afraid to quote from literature when it suited the occasion. He quoted from the poet Philip Larkin when speaking, as part of the ICLR Annual Lecture series in 2013, on “Marriage from the Eighteenth Century to the Twenty-first Century: Some reflections on Hyde v Hyde and Woodmansee (1866) LR 1 PD 130.”

The whole speech (now published on BAILII) repays close study. It demonstrates not only the breadth of his erudition and interest in history but also his skill as a writer. The quote from Larkin came from the poem Annus Mirabilis (“Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three”…) but, given that the topic was family law, and the observation was a wry one, he might equally have quoted from This Be The Verse.

The lecture examines how the idea of marriage and what constituted a family had changed, into something that might be almost unrecognisable to the Victorian judges who sought to define it in law. (The lecture was given at a time when Parliament was considering whether to legalise same-sex marriage, which it then did.)

“The result of all this is that in contemporary Britain the family takes an almost infinite variety of forms. Many marry according to the rites of non-Christian faiths. People live together as couples, married or not, and with partners who may not always be of the opposite sex. Children live in households where their parents may be married or unmarried. They may be brought up by a single parent. Their parents may or may not be their natural parents. They may be the children of parents with very different religious, ethnic or national backgrounds. They may be the children of polygamous marriages. Their siblings may be only half-siblings or step-siblings. Some children are brought up by two parents of the same sex. Some children are conceived by artificial donor insemination. Some are the result of surrogacy arrangements. The fact is that many adults and children, whether through choice or circumstance, live in families more or less removed from what, until comparatively recently, would have been recognised as the typical nuclear family.”

As well as marriage and divorce, both before his term as President of the Family Division and afterwards, Sir James also grappled with questions of mental capacity and the Court of Protection, with deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLs), and, more recently, the current parliamentary debates over assisted dying. He was deeply critical of the expectation of judicial involvement without sufficient safeguards or resources in the current Bill, as he explained in a series of posts on the Transparency Project blog, of which he was a long time supporter. He was also, in his retirement, a regular contributor to the Financial Remedies Journal.

Prior to his appointment as President, he had served as chair of the Law Commission, charged with law reform more generally, and he continued to engage with its projects, notably the recent proposals on changes to the law on contempt.

His legacy, in his contribution to the law, is not in doubt. As a man he was always warm hearted and approachable, with none of the pompousness or affectation of senior office. He will be remembered with both admiration and affection, as demonstrated in the many other tributes already published.

Law Society Gazette: ‘Moral clarity and compassion’: Former family chief Munby dies at 77

Lucy Reed KC, Pink Tape: R.I.P. Sir James

Joshua Rozenberg, A Lawyer Writes: Sir James Munby

Mark Neary, Last Ride On The Clapham Omnibus

Wadham College, Oxford: We were saddened to learn of the death of Sir James Munby

Photo of Sir James Munby, taken by Paul Magrath at The Law Society in 2019.