Smoke, spirits and statute

In this guest post James Hickman considers the trial of Helen Duncan and provides a brief history of English witchcraft laws… Continue reading about Smoke, spirits and statute

“When do you think …”, asks Time Team stalwart Tony Robinson, was the last time that “someone in the UK was put in prison for being a witch?”

Those are the headline-grabbing opening words of Robinson’s TV programme, The Blitz Witch. The question is designed to shock—and the answer he gives (Helen Duncan, in 1944—yes, 1944) also certainly does. But the truth behind the sensationalism is rather more complicated.

Fear, law and the early statutes

Witchcraft has long occupied a curious space between folklore, fear and law. In Tudor England, the first Witchcraft Act was passed in 1542 during the reign of Henry VIII. It made the practice a crime punishable by death, the same penalty reserved for treason and heresy. This was no idle gesture: the law reflected genuine anxieties about magic and maleficium—harmful spells, charms and potions—believed to endanger both souls and kingdoms.

That Act was repealed only five years later by Edward VI, but the pendulum swung back with Elizabeth I’s statute of 1563. This law distinguished between “minor” offences (where no harm was caused) and “major” ones (where death or injury resulted). The harsher category could lead to execution. The Elizabethan statute came at a time when the Protestant Reformation was shaping ideas of good and evil, and witchcraft was readily cast as a tool of the devil.

Under James I, fear of sorcery was elevated into obsession. James had himself been caught up in witch trials as King of Scotland—the infamous North Berwick trials of the 1590s, in which dozens of women were accused of conspiring to kill him. He even took it upon himself to personally cross-examine suspects under torture. In 1597 he published Daemonologie, a treatise on witchcraft and necromancy, which presented witchcraft as a tangible threat to Christian society.

When James inherited the English crown in 1603, his paranoia followed him. The 1604 Witchcraft Act expanded the Elizabethan law, making it a capital offence to “invoke any evil spirit”, regardless of whether harm could be proven. It was under this statute that the witch-hunts of the 17th century reached their peak.

Witchfinders and judges

The law emboldened the likes of Matthew Hopkins, East Anglia’s self-styled “Witchfinder General” of the 1640s. Hopkins had no official office but, in the upheaval of the Civil War, local magistrates turned to him for authority. Armed with the 1604 Act and questionable “tests” such as swimming suspects or searching for the devil’s mark, he was responsible for more than a hundred executions in only a few years.

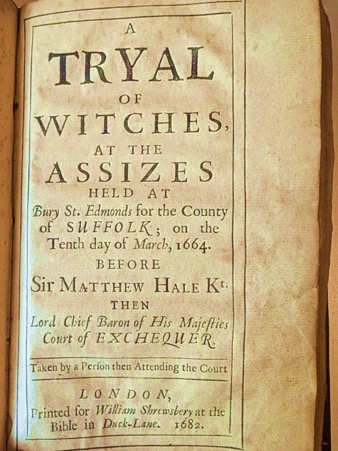

But witch-hunting was not confined to self-appointed enforcers. Learned judges also upheld the law. In 1662, Sir Matthew Hale presided over the trial of two widows, Amy Denny and Rose Cullender, at Bury St Edmunds. Hale, one of the most respected jurists of his age, assured the jury that witches were real, and upon conviction he sentenced both women to death. His judgment lent legal credibility to witchcraft prosecutions and was cited in support of later trials—even across the Atlantic, at Salem in 1692.

The Bideford witches of 1682—Temperance Lloyd, Susanna Edwards and Mary Trembles—were the last to be executed for “witchcraft” in England. Condemned on the basis of hearsay, flimsy evidence and forced confessions, their tragic deaths mark the grim endpoint of capital punishment for the crime, but not the end of trials.

The changing tide

By the early 18th century, scepticism was creeping into the courtroom. The case of Richard Hathaway illustrates the changing tide.

In 1701, blacksmith’s apprentice Hathaway accused a widow, Sarah Morduck, of bewitching him. He was found to have “falsely, maliciously and knowingly” claimed that he could not eat (and had vomited pins and nails) as a result of his “pretended Bewitching”. Despite public support for Hathaway (illustrating lingering common belief in witchcraft), Morduck was acquitted.

A year later, Hathaway himself was charged with imposture. At the Surrey Assizes in 1702, Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt convicted him, turning the law’s focus away from supposed witches and onto false accusers.

The climax of this sceptical turn came with the Witchcraft Act of 1735. This Act declared that witchcraft and magic were not real. The crime became not practising witchcraft, but pretending to do so. Fraud replaced sorcery, and the penalty was imprisonment or a fine, not death. It also meant that to accuse someone else of witchcraft was itself potentially criminal—a recognition that such accusations were malicious rather than meaningful.

This was a decisive legal break. The statute books no longer upheld belief in the supernatural. And yet, as folklore attests—with witch bottles buried in cottages, charms nailed to doorways and spirits invoked in private rooms—popular belief in magic was not so easily extinguished.

Modern shadows

Two centuries later, witchcraft was still on the books—at least in name. The Witchcraft Act 1735 remained law into the 20th century, though its application had narrowed to fraudulent mediumship.

It was under this statute that Helen Duncan, a Scottish medium, was brought to trial in 1944. In Second World War Britain, with the threat of invasion looming, she held séances in which she allegedly spoke to the spirits of recently departed servicemen, to the great comfort of their families. In one sitting, she declared that HMS Barham had been sunk—knowledge the Admiralty had kept secret. With over 800 sailors lost, and D-Day on the horizon, the authorities took alarm.

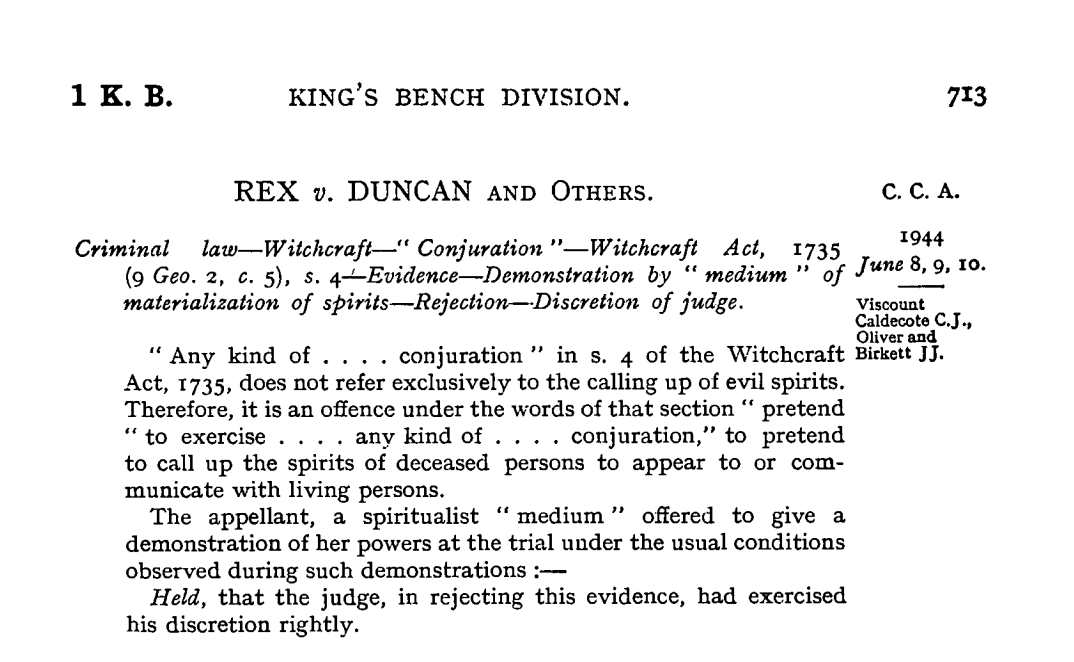

Unable to prove espionage, they fell back on the Witchcraft Act. At the Old Bailey, Duncan was accused not of treachery, but of “pretending to conjure spirits”. She offered to prove her powers with a live séance in court. The judge declined, and she was sentenced to nine months in Holloway Prison.

Her conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeal in R v Duncan [1944] KB 713, which confirmed that the 1735 Act’s language extended to any fraudulent claims of spirit communication, regardless of whether the spirits invoked were “evil” or benign.

Many saw the trial as a show trial: a performance designed to silence mediums, reinforce secrecy and warn against the careless spread of rumours. It was sensational enough to draw headlines as the “last witch trial” in England—though the truth was subtler.

Misconceptions

Two myths persist about Helen Duncan. The first is that she was convicted for being a witch. She was not: the Witchcraft Act of 1735 had expressly abolished that idea, making it an offence only to claim and pretend to use magical powers. The second is that she was the last person convicted under the Witchcraft Act. In fact, that was Jane Rebecca Yorke, a 70-year-old medium fined later in 1944. Duncan remains the last person to be imprisoned under the statute, but not the last convicted.

Conclusion

The story of England’s witchcraft laws is one of persecution and evolution, and a mirror of society’s fears. In the 1600s, Matthew Hale’s words gave deadly weight to superstition, while by the 18th century, cases like Richard Hathaway’s exposed fraud and deception.

The 1735 Witchcraft Act may have demonstrated that courts were no longer willing to persecute. Yet Parliament only finally removed the word “Witchcraft” from the statute books when repealing the Act in 1951—bringing about its own kind of stigma for the likes of Duncan, who was convicted before this.

And so, contrary to the sensationalist headlines, Helen Duncan was not convicted for being a witch. Instead, she was caught between paranoia and centuries-old statute designed to expose the truth. Her case wasn’t so much about fear of the supernatural, but about secrecy, morale and control.

But one mystery remains. Just how did she get her classified information?

James Hickman is a Desk Editor at ICLR. A keen historian, he is a published children’s storybook author and was previously Head of Computing at Great Bradfords Junior School in Braintree, Essex.

Featured image: Helen Duncan (Wikimedia commons).