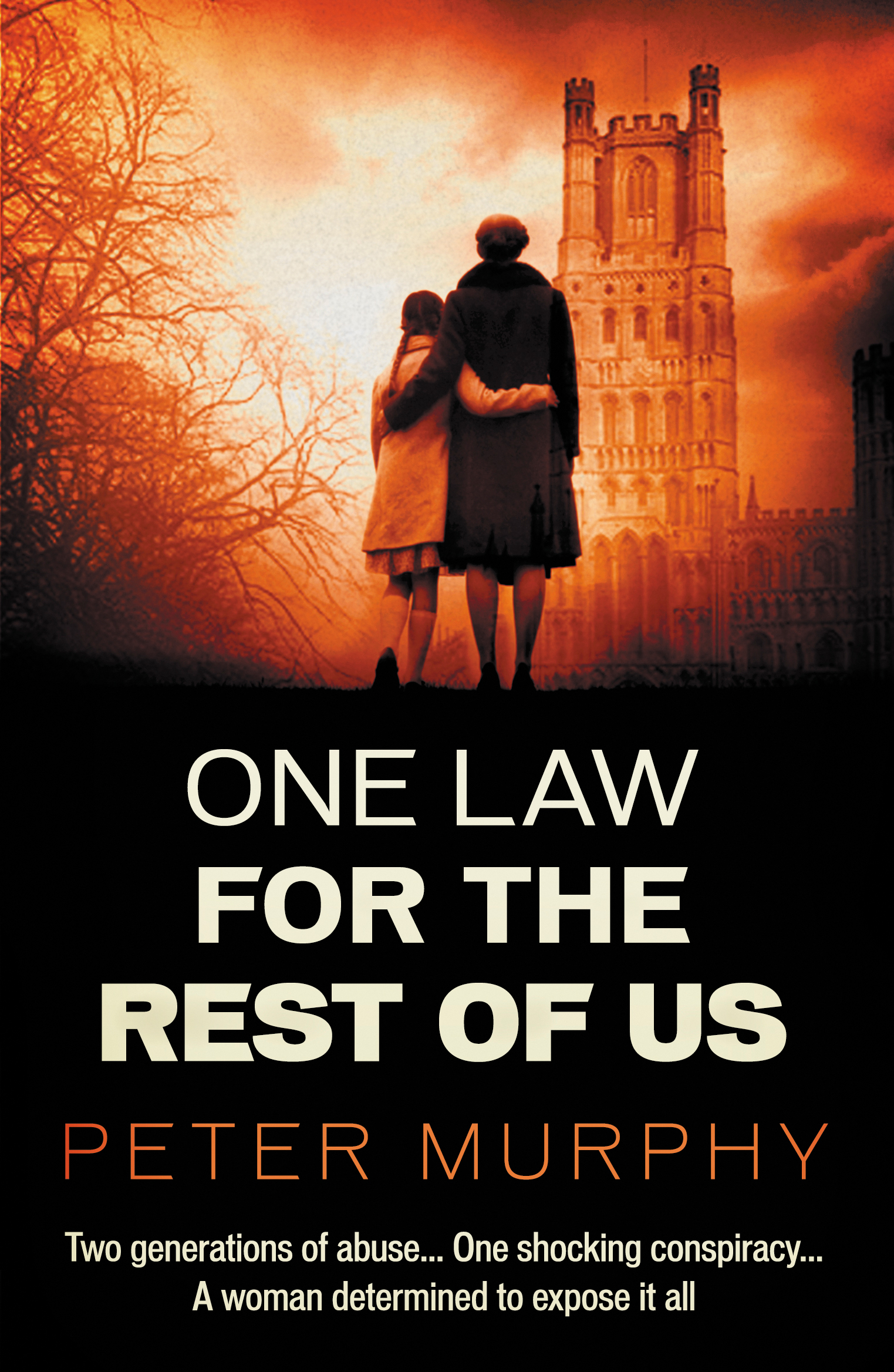

Book review: One Law For the Rest of Us, by Peter Murphy

The latest novel to chart the career of Peter Murphy’s increasingly successful young criminal barrister Ben Schroeder combines the horribly contemporary issue of historic sexual abuse with a gripping courtroom drama in which the laws of evidence and the interests of national security are in play, set during the murky political era of the early 1970s.… Continue reading

One Law For the Rest of Us is narrated in part by Audrey Marshall, one of the complainants in a case of sex abuse (in her case historic sex abuse) against a Church of England boarding school. Unusually, perhaps, both she and her daughter complain of being abused in the same school. In Audrey’s case, she claims that it was only after her daughter’s complaint came to light that she recovered her memory, long suppressed, of the abuse which she herself suffered, in her own time at the same school. But do we believe her?

“If it hasn’t happened to you, I can’t adequately explain what it feels like.”

We are predisposed, now, in 2018, to treat allegations of historic sex abuse with some scepticism, especially where they involve recovered memories. We are emerging from a time of turbulence in the treatment of such offences, when, after a long period of sweeping such claims under the carpet, the police and justice system were forced to take them seriously, and the pendulum swung the other way, invoking a tendency to accept the wildest accusations on the grounds of a need to ‘believe’ the ‘victims’ of sex abuse rather than expecting them, like anyone else reporting a crime, to cooperate with an investigation in which such allegations were tested against whatever evidence could be gathered.

With the Henriques report, and the collapse of Operation Midland, the pendulum has swung back a bit, hopefully to somewhere in a more median position. Even the flood of new complaints from the entertainment and hospitality industries following the #MeToo campaign have been treated with less feverish credulity than the earlier claims against Establishment paedophile rings and the like in the wake of the Savile scandal.

The reason I mention all this is because the events described in the narrative all occurred in or before that earlier period, when complainants were not automatically believed, but the reputation of recovered memories was also less besmirched by scandals of fraudulence and quackery.

The events of which Audrey has recovered her memory so dramatically took place in the early 1940s, when, like so many children, she and her older sister (Joan) were evacuated to the countryside of East Anglia to escape the bombs of World War II. Joan seems to have escaped the mysterious ritual by which Fr Gerard, the supposedly reverend headmaster of their C of E boarding school, would slip into the girls’ dormitory after lights out and summon one of them to pad downstairs in her nightie and be ushered into his private library, where a small groups of respectable looking men would take turns to fondle and abuse her for their own pleasure; but she knew it was going on, and her powerlessness to prevent it haunts her ever after. Audrey coped with the trauma by suppressing any recollection of it – so much so that when an opportunity comes for her daughter to attend the same prestigious school, she takes up the offer with expected parental pride. But then, when her daughter reports her own experience of inappropriate touching, the memories all come flooding back, and with them the shame and trauma. That, at any rate, is the version presented for the prosecution.

Ben Shroeder is instructed for the Crown, alongside another junior barrister, Virginia Castle, familiar from earlier in the series, and led by Andrew Pilkinton QC, senior prosecuting counsel at the Old Bailey. Arraigned alongside Fr Gerard in the dock are three men, prominent in public life, whose names are by order of the court concealed behind initials. Who are Lord AB, Sir CD and the Right Revd EF? They have been identified from photographs in the press – they say mistakenly. But who was the fourth man also said to be present in Fr Gerard’s library during the events in question?

As well as having to contend with the sneering cynicism and what we might now call forensic trolling of counsel for Fr Gerard, the wily Anthony Norris, the Crown’s team must tackle some very real difficulties with the evidence. For example, although the law and practice have since changed, at the time a child’s evidence of sexual assault required corroboration from an independent source. (This was long before the era of ABE guidelines.) Can Audrey’s evidence, based on her recovered memory, corroborate that of her daughter Emily? If Audrey’s evidence is discredited, that would deny the corroboration on which Emily’s depends. Unless, of course, they can find another witness… someone else who might have been abused. But if no one is coming forward, why might that be? Have strings been pulled to prevent this – or them – coming out? In short, is there one law for the rich and powerful and another, as the title asks, for the rest of us?

It is the wider picture of how society operated in those days, of the persistence of class and rank in spite of the apparent abandonment of deference during the sexual and social revolution of the 1960s, and of the sinister machinations behind the democratic façade of public life, that make this novel much more than a superb courtroom thriller.

One Law for the Rest of Us, by Peter Murphy (No Exit, £9.99)