The Court of the Future: HMCTS Change Event at MOJ

On 2 November 2017 the Ministry of Justice hosted an HMCTS Public Community Change Event to showcase some of the work being done in the course of its current £1bn overhaul of the court system. Paul Magrath was there. [Post updated 17/11/17.] The Ministry of Justice in St James is an imposing and somewhat dystopian… Continue reading

On 2 November 2017 the Ministry of Justice hosted an HMCTS Public Community Change Event to showcase some of the work being done in the course of its current £1bn overhaul of the court system. Paul Magrath was there. [Post updated 17/11/17.]

The Ministry of Justice in St James is an imposing and somewhat dystopian building to look at outside, but once inside it feels rather more like an airport, with its security scanners, its vast central atrium, and a constant buzz of chatter and activity. Down in the well of the atrium is a general waiting area with an abstract sculpture and occasional seating, and it was here that we gathered, some 70 or 80 of us I would estimate [Update: the MOJ later told me it was nearer 120], to hear the justice minister Dominic Raab introduce the day’s event.

Things got off to a slightly rocky start, with the PA system not working and the general hubbub of the building above and about us making it hard to hear the speakers; and what with that, and the buzz-phrases, and the modern architecture, it was all a bit W1A. The only thing missing, as the Old Bailey judge next to me commented, were the folding bicycles.

The purpose of the event was to get court users of various descriptions to see and try out some of the new technology and design being introduced as part of the HMCTS Reform programme. This is a massive endeavour, with lots of constituent projects. The £1bn assigned to HMCTS (Her Majesty’s Court and Tribunal Service) for the Reform programme is partly being funded by selling off some of the old court estate property, but the majority of it is coming straight from the government which, back in the day when Chris Grayling was Lord Chancellor, seems to have woken up and realised that a court system which had changed little since, say, ICLR was set up in 1865, was probably in need of a bit more than a sticking plaster upgrade.

I’ve written about various aspects of HMCTS Reform here on this blog and elsewhere, including:

A justice system fit for the future

Online courts and cyber judges

Justice Online: just as good? Joshua Rozenberg on the online court

Justice down the rabbit-hole: Fulford LJ on the Rise of the Cyber Judge

See also: the Inside HMCTS blog for updates from those involved in the Reform programme

Introductions

As well as the introduction from Dominic Raab, we also heard from Susan Ackland-Hood, CEO of HMCTS; from Richard Goodman, Change Director, HMCTS; Sidonie Kingsmill, Customer Director, HMCTS; and Kevin Sadler, Deputy CEO and Courts and Tribunals Development Director, HMCTS.

However, I was particularly interested to hear from one of the judges involved in the project, Mr Justice Robin Knowles, who is chair of the Litigant in Person Engagement Group, which advises the HMCTS Reform programme on the needs of pro bono and unrepresented court users.

Sir Robin emphasised four points :

- The project was about different groups – civil servants, judges, lawyers and users, all working together to serve the public interest.

- We were no longer at the beginning but were now some way in to the project, though there was still a long way to go. Trust and respect had been built up to such an extent that it was now possible for those involved to be frank with one another in commenting on the development.

- Progress was being made, and although some of it was not directly part of the Reform programme, it was inspired by the programme. The public, private and pro bono sectors were complementing one another.

- This was a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make lasting change for good. We should not dwell on what may have gone wrong, but focus on what could be done to make things better.

( I noted these eagerly at the time, as you do, but reading them back it sounds a bit like a pep talk. )

The sessions I attended conveniently described three different aspects of what might be termed the Court of the Future.

The Court of the Future: physical courts

Although many of the old bricks-and-mortar court buildings have been sold off, the vast bulk of the legacy court estate remains in place and the plan for those buildings is to maximise their utility. That may or may not involve flexible operating hours (see below, if you can bear to) but it does mean refurbishing and maintaining the buildings to a higher standard and a more modern design.

The way the maintenance contracts are managed has changed, we were told, to make it easier and quicker to repair and maintain lifts, heating, roofs and other aspects of the fabric of the building. The installation of wifi in all courts, long overdue, was now largely complete.

In terms of design, I was shown a number of features of the new Design Guide. One aspect of this is court signage. This will involve bigger, clearer signs directing people to different courts within a building, and make better use of colour. For example, each floor would be colour-coded, and all the court signs within that floor would use the same colour. Next to the lift door would be a list of courts and offices on all the floors, in the various different colours, so court users getting out at a particular floor would immediately know if they were on the right floor. Having found the right court, they would then find the furniture and lighting has been modernised, partly to make the layout clearer and partly to enable it to be modified and adapated to different types of court process. The latter would only apply in civil / family court complexes – criminal courts would require a jury box and/or a dock, which would not necessarily be possible in a civil type of courtroom.

The new signage is going to be tested in civil justice centres in Cardiff, Birmingham and Hull, so if you are near one of those you may have the chance to provide some feedback.

The Court of the Future: digital case management

The Old Bailey judge I spoke to said he was very pleased with the current electronic document management system called Crown Court DCS or Digital Case System. This is outside the Reform programme, having been developed by a private company, CaseLines. It is basically a system for managing the upload, storage, access to and presentation of digital case documents, such as witness statements and trial bundles, and digital evidence, including audio/visual evidence.

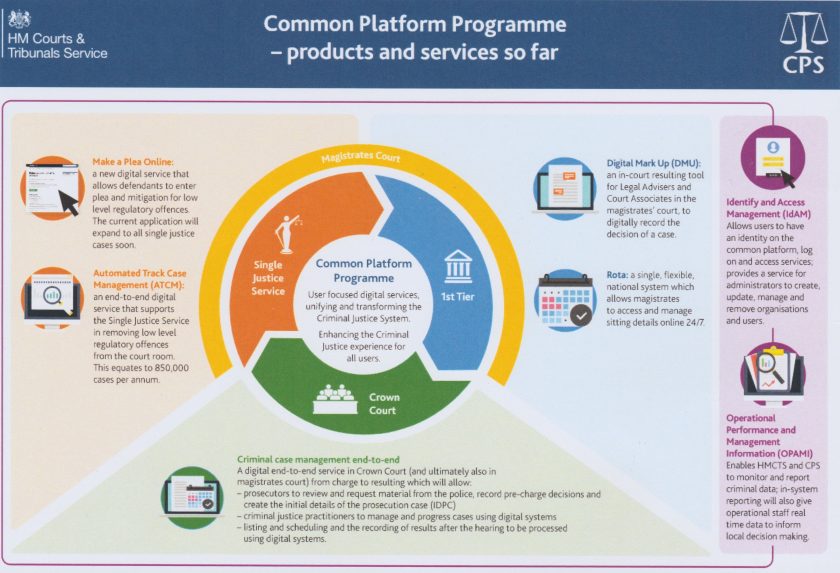

The Criminal Justice System (CJS) Common Platform is an in-house HMCTS development, so there are no immediate plans for it to incorporate the DCS (which is also available in a version adapted for family court hearings), though I was told it will eventually duplicate many of its features. The common platform is designed to replace existing case management systems with a single end-to-end system providing access to all the material necessary to deal with cases without having to pass material from one agency to another, covering the police, CPS, courts and prison service. This will hold the latest, most complete version of the case material and can be accessed by everyone who needs to, from almost anywhere, at any time.

The bit of this I saw in action related to recording case results in the Crown Court where the defendant had been referred by the magistrates’ court, on a guilty plea, for sentencing. The case is called up from the common platform and the plea confirmed, then the sentence recorded and saved, thus avoiding a process of recording in longhand on a document later to be passed to a back office team to type the result into another system. A small agile step for a tech-savvy person, you might think, but a giant step for the lumbering behemoth that is the criminal justice system.

Something similar is also being developed for the civil and family courts, though not necessarily from the beginning of the process. Thus while online applications for divorce and probate have been developed a the beginning of the process and are being trialled with the public, when it comes to social security or child support appeals the development has begun in the middle, as it were, with a system to allow them to track their tribunal appeals online and receive text message updates.

The next phase of the project, according to Susan Ackland-Hood, will include an end-to-end document management and digital evidence storage and presentation system that can be used for both public law family cases (including care and adoption cases) involving local authorities, practitioners and representative groups, and private law family cases and other types of civil claim.

The Court of the Future: virtual hearings

The presentation about virtual hearings was more about their etiquette and procedure than about the substantive development of technology, since the latter was fairly unremarkable. Once you have digital case management and e-bundling, and you can use email to all the parties to make an appointment for the hearing, all you need is a standard type of video conferencing platform, albeit with minor modifications.

The set-up is classic BYOD (bring your own device). The intention is for those involved to use their own equipment, which will generally be a laptop (though it may be possible to use a tablet or phone). It needs to have an in-built camera and mic. More importantly, though, the camera angle needs to be arranged so that the other parties can see a good frontal view of the participant’s face, not a chin-angled nostril-focused selfie-shot.

Look at yourself in the monitor frame: is there a flower-pot growing out of your head or an awkard mirror or stain on the wall behind you? Ideally, there should be a plain wall or something undistracting behind you. For the judge, there might be a lion and unicorn coat of arms as appears in physical court rooms. Or conceivably, as one questioner suggested, this could be added by way of an overlay.

The judge invites the other participants to join, pending which they are in a virtual waiting room. It is possible for one or more parties to conference before the hearing, eg to settle at the virtual doors of the court. But then the countdown begins, visible on each participant’s screen, until the judge’s appearance. All parties can then see each other on the screen, in separate frames. Each signs on and introduces themselves both in writing for the caption on their screen image and orally for the benefit of the other participants.

In terms of etiquette, it may need to be made clear that, for example, if one is visibly looking down it may be because one is taking notes or reading them, and likewise one should avoid standing up (no need for the usher’s call to “be upstanding in court”, otherwise you’d just see everyone’s midriffs on screen). Clarity of speech may need to be more emphatic to compensate for the limitations of mics and sound systems. It may be necessary to pause occasionally and allow others to indicate, perhaps by waving, that they wish to interrupt. But none of this will come as a surprise to anyone who has ever had a Skype conference or JoinMe session.

Featured image: “Strategy Wheel” from the HMCTS blog.

This post was updated on 17 November 2017 to include an infographic of the Common Platform.