Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR, 4 November 2019

This week’s roundup comes from Brisbane, where Team ICLR are continuing their tour of Australia. Because of this, we have had less time to devote to legal stories developing back home, so coverage is more brief (and a little later) than usual.… Continue reading

ICLR news

Queensland (law) reporting

Team ICLR is in Brisbane this week for talks with the Supreme Court Library and the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for Queensland, who are collaborating on a project to publish the authorised law reports together with all the unreported judgments of the courts of Queensland and make them all freely available to everyone. That they can afford to do this is due in part to a lucrative monopoly on compulsory legal advertisements in the Queensland Law Reporter and in part to state funding.

At present the Queensland Judgments website includes a complete set of the authorised law reports of the Supreme Court of Queensland (Queensland Reports) and a set of the unreported judgments since 2002 of the Supreme Court (Trial Division and Court of Appeal). The judgments and reports are available and searchable in full text view and also as PDFs. All the unreported judgments, along with those of other courts (district courts and even some magistrates’ courts where written reasons are given) are also available in the CaseLaw section of the Supreme Court Library of Queensland website, which also houses information about the courts, the judiciary, and the fabulous legal educational resources of the Sir Harry Gibbs Centre.

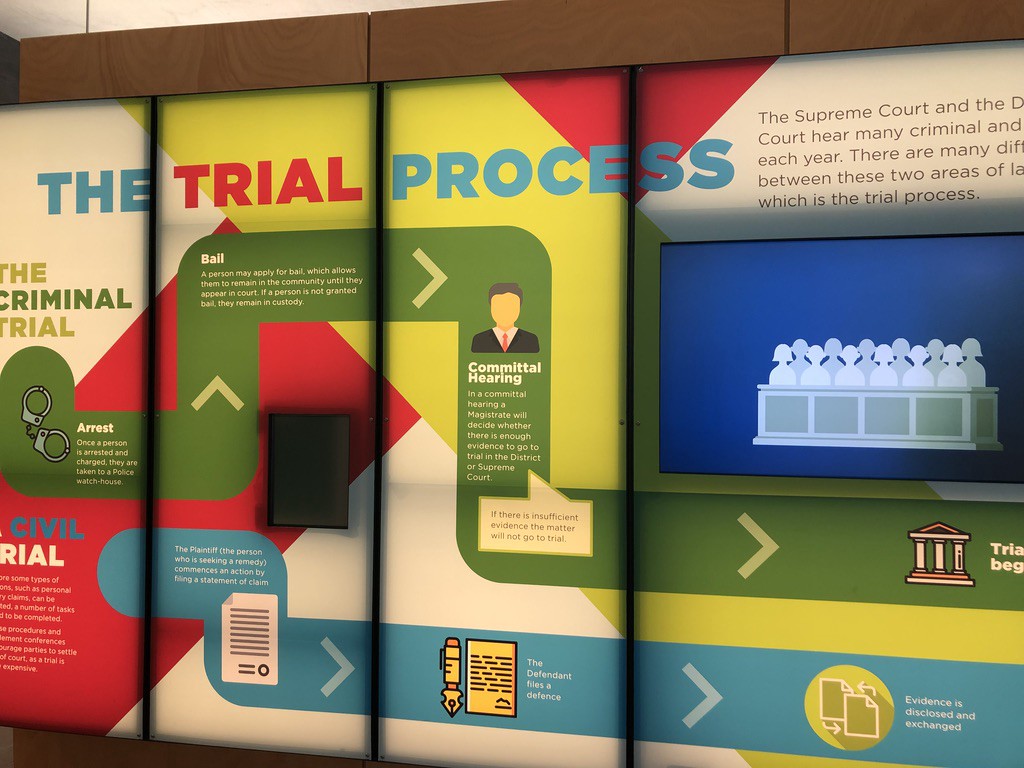

Among the resources of the latter is an exhibition aimed at visiting school groups as well as curious members of the public, about the legal system of Queensland.

Without Fear or Favour provides a graphic explainer about both civil and criminal trial processes, and there are exhibits about Queensland’s legal history, the fate of transportees and convicts, the land rights of Aboriginal peoples, and the development of Queensland’s innovative Criminal Code 1899.

The clarity and usefulness of these exhibits, and the mock trials, chats with judges and other facilities offered by the Supreme Court to visiting schools and groups are all most inspiring. The general theme supports the idea that the law belongs to everyone, and everyone is entitled to know and have access to as much knowledge about it as they want or need. It’s a philosophy we would like to apply in England and Wales, and in large measure we already do so — only most of it is done voluntarily and unofficially, by charitable and pro bono groups and individuals. Something to think about, perhaps, as we embark on this year’s Pro Bono Week (about which more in our next roundup).

As for ICLR — we are here to collaborate, with the ICLRQ and SCLQ, as well as the respective law reporting councils of New South Wales and Victoria, in a project to provide embedded links to each other’s content wherever a relevant citation from another publisher’s case appears in our own content (a bit like the way ICLR currently links to and from BAILII in the UK). It’s still being developed, though some links have been implemented already, and we hope to report on further progress before too long.

On the evening of 4 November, we jointly hosted with ICLRQ an event at the Banco Court in Brisbane, at which Paul Magrath from ICLR gave a presentation on the current and future development of our online platform and the data research projects currently underway via the ICLR&D “lab”.

Brexit

Extension, election and more…

When Team ICLR left for Singapore and Australia a fortnight or so ago, the prospects remained high for a “no-deal” exit on 31 October, as promised / threatened by the Prime Minister with dire talk of his preferring to be dead in a ditch if Brexit didn’t happen (with or without a deal) by that deadline. We had visions of being unable to return to the country because the airports were choked with passport queues and planes unable to land, while all the ports would be clogged up with lorries full of rotting produce waiting to complete customs checks. But Halloween came and went without either smashed political pumpkins or the riots forecast by some.

Instead, we have been favoured with another extension of the article 50 notice period, thanks to the “Benn Act” and a further round of indulgence on the part of the EU negotiators, this time until 31 January. This additional period for negotiation or persuasion will not be wasted — or not much — because instead of that we are going to have a general election, on 12 December, with a view to whoever wins it and forms a government then having a few short weeks to sort out the next step. Which might be another Brexit deal. Or another referendum. Or both. And in the meantime we have a new Speaker in the House of Commons, just as it retires for a bout of election fever.

It’s all a bit like one of those TV dramas which, after a mildly successful first run, is trotted out for a second, third and fourth series, each less wittily and more desperately plotted than its predecessor, in a vain effort to maintain viewing figures that must, inevitably, dwindle: we might call it Brexit, the Boxed Set.

For more cogent analysis of what has been going on in politics, see

- Obiter J, on the Law and Lawyers blog: A December General election ~ the Speaker ~ Dissolution of Parliament

- David Allen Green, The Law and Policy Blog: Brexit and the general election and Another Brexit day comes and goes — Hallowe’en 2019

Privacy

Human Rights committee report

In its third report of the 2019 session, The Right to Privacy (Article 8) and the Digital Revolution (HC 122; HL Paper 14; published 3 November 2019), the Joint Committee on Human Rights reports serious grounds for concern about the nature of the “consent” people provide when giving over an extraordinary range of information about themselves, to be used for commercial gain by private companies.

The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. This report was the result of an inquiry, begun in the 2017 parliamentary session, into “whether new safeguards to regulate the collection, use, tracking, retention and disclosure of personal data by private companies are needed in the new digital environment to protect human rights”.

The report finds that the current safeguards are inadequate and that people using internet services are largely unaware of the risks of engagement and the terms on which that engagement with online services is provided. In particular, the “consent” model (giving people the illusion of control over the use of their data) is, the committee says, “broken”.

“The evidence we heard during this inquiry, however, has convinced us that the consent model is broken. The information providing the details of what we are consenting to is too complicated for the vast majority of people to understand. Far too often, the use of a service or website is conditional on consent being given: the choice is between full consent or not being able to use the website or service. This raises questions over how meaningful this consent can ever really be.”

This “bogus” reliance on consent is, the report says, “in clear conflict with our right to privacy”. The ability to target advertisements and other content at users based on the data profile derived from their usage could result in the sort of blatant discrimination that, in traditional print advertising, would be far more obvious. The data being used (often by computer programmes rather than people) to make potentially life-changing decisions about the services and information available to users might not even be accurate, but based on inferences from other data. Yet the individual had no way of finding out what judgements had been made about them.

“We were left with the impression that the internet, at times, is like the ‘Wild West’, when it comes to the lack of effective regulation and enforcement.”

The Committee calls on the Government to ensure there is robust regulation over how our data can be collected and used and it calls for better enforcement of that regulation.

Public order

XR banning order ruled unlawful

The decision to ban all Extinction Rebellion protests across London on 14 October 2019 has been found to have been made unlawfully, in judicial review proceedings brought by Baroness Jenny Jones and others against the Metropolitan Police Commissioner. We initially reported on the claim in Weekly Notes 21 October 2019.

The claimants sought to challenge the decision by Superintendent Duncan McMillan to impose a condition on the “Extinction Rebellion Autumn Uprising” (“XRAU”) on Wednesday 14 October 2019 using powers under section 14(1) of the Public Order Act 1986. The condition was that

“Any assembly linked to the Extinction Rebellion ‘Autumn Uprising’ (publicised as being from 7th October to 19th October at 1800 hours) must now cease their protest(s) within London (MPS & City of London Police Areas) by 2100 hours 14th October 2019″.

In its judgment, R (Baroness Jones) v Comr of Police of the Metropolis [2019] EWHC 2957 (Admin); [2019] WLR(D) 618, the Queen’s Bench Divisional Court (Dingemans LJ, Chamberlain J) first found that some of the claimants did not have standing to bring the claim, but others did, so it could proceed. The court went on to decide the critical point of statutory construction on which the case turned, which is explained in the court’s media summary as follows:

“On the third issue the Court considered the wording of the 1986 Act, the earlier 1936 Public Order Act and the White paper leading up to the enactment of the 1986 Act, and relevant authorities on the 1936 and 1986 Act. In the light of the wording of section 14 requiring the senior police officer imposing the condition to be present at the “scene”, and the definitions of “public assembly” and “public space” in section 16 as appears from paragraph 66 of the judgment, the Court decided that the words “public assembly” must be in a location to which the public or any section of the public has access, which is wholly or partly open to the air, and which can be fairly described as a “scene”. Separate gatherings, separated both in time and by many miles, even if co-ordinated under the umbrella of one body, are not a public assembly within the meaning of section 14(1) of the 1986 Act. The XRAU intended to be held from 14 to 19 October 2019 was not therefore a public assembly at the scene of which Superintendent McMillan was present on 14 October 2019. Therefore the decision to impose the condition was unlawful because there was no power to impose it under section 14(1) of the 1986 Act: see paragraphs 65 to 72 of the judgment.”

On this reading, it seems that it was the very fact that XR used the tactic of multiple decentralised or distributed protests and demonstrations, organised at different places and times, that deliberately or otherwise had the effect of frustrating any such simple fix as the police intended under section 14 of the Act. The simple fix was a “one ban stops all” approach, which was basically too wide and (given the penal consequences of breach) insufficiently particularised (as we say in the law).

The court granted a quashing order, basically cancelling out the original banning order. But any victory for XR may be short lived. Even if the police do not appeal on this point (though it seems likely they will, for the sake of future clarity), it was clear that the section 14 banning order route might not be their only option. The media summary notes:

“It … was common ground that there are powers contained in the 1986 Act which might be lawfully used to control future protests which are deliberately designed to “take police resources to breaking point”, to use the words set out in the October Rebellion Action Design (set out in the final sentence of paragraph 16 of the judgment).”

Interesting reads

Barbara Rich (on Medium) meditates on the “commorientes” rule (Latin for “people who die simultaneously”) in s184 of the Law of Property Act 1925, in relation to disputes over the inheritance of the connected estates of two persons (usually related or married) who both die in circumstances where the precise order in which they died is unclear from the evidence; its effect in the recent case of Scarle v. Scarle [2019] EWHC 2224 (Ch), and some of the myths of public understanding that have sprung up about the case (which is now reported in the Weekly Law Reports: [2019] 4 WLR 119).

David Pocklington on the Law and Religion UK blog considers the health effects of electromagnetic radiation that have been addressed by the consistory (ecclesiastical) courts to date, including objections on the grounds of electro-hypersensitivity, in the context of “scare stories” about the installation of 5G technology in and around church buildings, and earlier posts relating to wi-fi in churches.

Tweet of the Week

is about a cliff. Or about Cliff. And a dangerously misplaced apostrophe.

Is he? Crikey. Thanks. I’ll keep my eyes peeled.

(This gold-standard apostrophe fail was brought to you by a gate at Trebarwith Strand, Cornwall.) pic.twitter.com/nlSBH1nk6O

— Nicholas Pegg (@NicholasPegg) November 5, 2019

Editorial standards at ICLR are so high, I am *quite sure* the likelihood of a misplaced apostrophe in a law report is vanishingly low, but who knows? If you spot one, let us know. It will join the small number of corrigenda (things to be corrected) with which our printed volumes occasionally begin. The main thing is that our reports are written by barristers and solicitors, not greengrocer’s. (Bless them.)

That’s it for this week. A bit shorter than usual, but we’re on the road (hence the lateness of posting). Thanks for reading, and thanks for the tweets and blogs and links to content from which this post was derived.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.

Featured image: the Story Bridge in Brisbane, and part of the Fortitude Valley shoreline. Photo by Paul Magrath.