Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR — 17 June 2019

This week’s roundup of legal news and commentary includes the Hong Kong extradition bill protests, proposed changes in the law on surrogacy, the reluctance of French judges to face digital scrutiny, and the semi-centenary conference of our British and Irish law librarians’ association.… Continue reading

Extradition

Hong Kong protests against new law

The past week has witnessed one of the largest demonstrations of political opposition in the world, as up to 2m people or nearly 30% of the population of Hong Kong came out onto the streets to express their objection to a new extradition law sought to be imposed by the chief executive of the Legislative Council, Carrie Lam.

Lam’s appointment was itself controversial, under a voting system whose lack of openness prompted the last major demonstrations in Hong Kong, the so-called Umbrella protests of December 2014 (see Weekly Notes, 15 December 2014) in which pro-democracy demonstrators had occupied the streets to draw attention to the failure to allow genuine candidates to stand for election to lead the Legislative Council. On that occasion they were protesting a decision by the mainland ruling Communist Party not to permit free and fair elections in Hong Kong, with candidates chosen by the people, despite an undertaking in the Basic Law and the handover agreement by which Hong Kong was ceded back to China in 1997. Instead, the CP wanted to impose its own candidates in what would amount to a travesty of democracy. Lam is seen by many as a puppet installed by the mainland Chinese government.

The extradition bill which prompted the latest protests would enable extradition on a case-by-case basis without legislative scrutiny to China, Macau and Taiwan. The law was proposed to deal ad hoc with situations for which no extradition treaty is currently in place. However it appears to be in conflict with the Basic Law (preserving the separate legal system of Hong Kong) and has prompted fears of its arbitrary use to silence political opposition. Moreover, China’s respect for the rule of law and human rights is in doubt, to put it mildly. That was only emphasised when Lam’s administration described the protests at one point as a “riot” and sent in the police with rubber bullets and teargas — something alarmingly reminiscent of the violent suppression of the Tain’an’men Square pro-democracy protests in Beijing on 4 June 1989, whose 30 year anniversary occurred earlier this month.

Attempts to defuse the situation, with Lam apologising and promising to suspend (not drop) the proposed law, have not had the desired effect, unsurprisingly. The protesters insist both she and the new law must go, for good.

See also:

- The Guardian, Hong Kong protests: pressure builds on Carrie Lam as public rejects apology

- South China Morning Post, When it’s hard to be humble: Carrie Lam’s harsh style even when backing down on Hong Kong extradition bill fuels public anger

- Hong Kong Free Press: Hong Kong protesters occupy roads around Gov’t HQ again, as huge anti-extradition law rally escalates and (on the law itself) ‘Trojan horse’: Hong Kong’s China extradition plans may harm city’s judicial protections, say democrats

And for a bizarre looking-glass view of the same events, China Daily, HK parents march against US meddling

Law Reform

Surrogacy law to be reviewed

“Surrogacy is where a woman bears a child on behalf of someone else or a couple, who then intend to become the child’s parents (the intended parents). Surrogacy is legal in the UK, and is recognised by the Government as a legitimate form of building a family,” according to the Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission. However, there are a number of problems with the current law, which is described as “not fit for purpose”, and the commissions are proposing a number of changes “to make sure the law works for everyone involved” and, in particular, to “put the child at the heart of the process”.

Under what is described as a new “pathway”, they propose to allow intended parents to become legal parents as soon as the child is born, subject to the surrogate retaining a right to object for a short period after the birth, instead of the current system whereby the intended parents have to apply to the court after the child has been born and do not become legal parents until the court grants them a parental order, often months later.

They also propose

- The creation of a surrogacy regulator to regulate surrogacy organisations which will oversee surrogacy agreements within the new pathway.

- In the new pathway, the removal of the requirement of a genetic link between the intended parents and the child, where medically necessary.

- The creation of a national register to allow those born of surrogacy arrangements to access information about their origins.

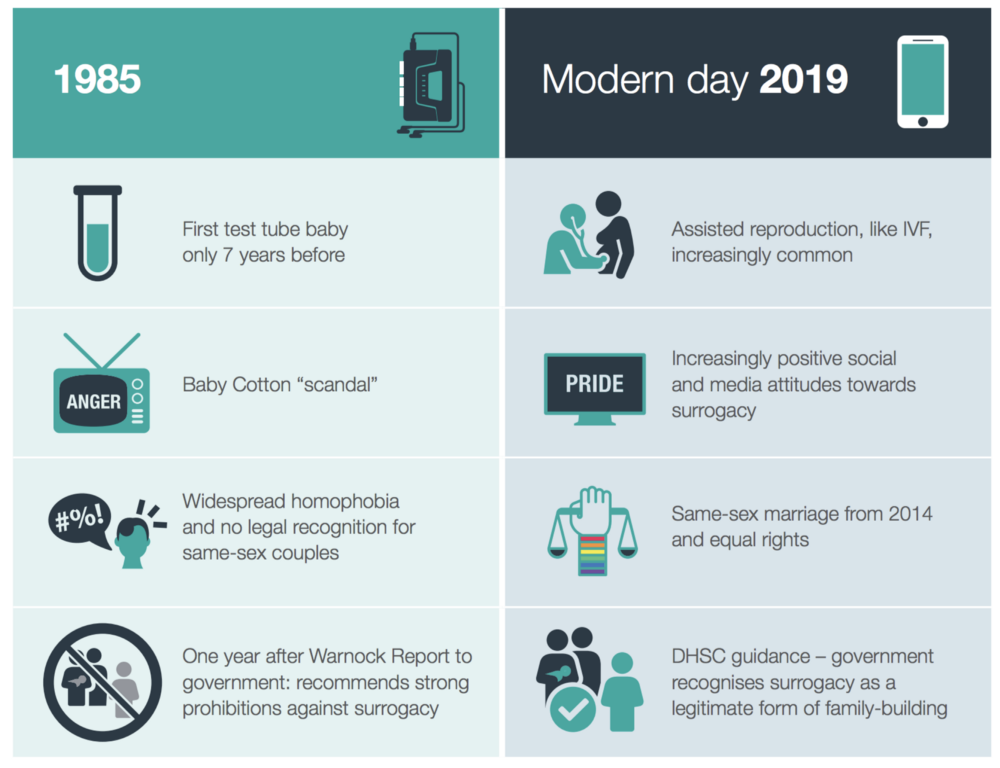

They also want to canvass the public’s views about surrogacy payments, for which there are no specific proposals as yet. They have therefore issued a consultation paper: Building families through surrogacy: a new law A joint consultation paper (which, at nearly 500 pages, is probably a bit more than an ordinary member of the public will want to wade through). A 24-page pdf summary is probably more digestible. This contains a rather amazing infographic of the social and technological changes since the enactment of the Surrogacy Arrangements Act 1985.

You can respond to the consultation using an online form, or by email to surrogacy@lawcommission.gov.uk

You can read about other projects in the Law Commission’s current financial year in Law Commission sets out its priorities for 2019/20

Legal information

BIALL conference 2019

The British and Irish Association of Law Librarians, founded in 1969, marked their 50th anniversary at this year’s conference, held in the seaside resort of Bournemouth, for which ICLR was a gold sponsor. The weather wasn’t quite glorious enough to justify widespread use of the pink, white and silver coloured flip-flops that ICLR were giving away at their stand in the exhibition hall, but an atmosphere of determined seaside jollity made up for any lack of actual sunshine — particularly at the Anniversary Party on the pier organised by platinum sponsors (and conference party supremos) Justis on 13 June, with cocktails and a suitably opulent cake (in 3 vols).

Happy 50th Birthday BIALL #biall2019 pic.twitter.com/4DIPCVp0UL

— Fiona Fogden (@1librarian) June 13, 2019

ICLR supported the welcome session for new and overseas delegates (also with cake), the President’s Reception was sponsored by Bloomsbury Professional, and the Annual Dinner and Awards at the Hilton Bournemouth by LexisNexis.

The Keynote Address and Willi Steiner Memorial Lecture was given by Baroness Hale of Richmond, President of the Supreme Court, reflecting on some of the major changes in the law and access to justice since she was an undergraduate at Cambridge in the early 1960s and Steiner was the law librarian there. (More on this in a separate post.)

Baroness Hale of Richmond DBE; the most senior judge in the U.K. giving her keynote address #BIALL2019 https://t.co/PBy5R9wrKS pic.twitter.com/LzqRpoHlds

— Helen (@HelenKielt) June 14, 2019

Among the other plenary sessions, David Allen Green gave his “Reflections on Brexit”, with a review of the seemingly interminable legal and policy nightmare of the government’s attempt to implement the 2016 referendum…

Excellent and entertaining talk from @davidallengreen: even more caustic in real life than on Twitter! 😉 #BIALL2019

— Antoine Dusséaux 柳华 (@ADssx) June 13, 2019

and Kevin Poulter, in a session titled “The Social Media Revolution? The impact on lawyers and law firms”, discussed the benefits and pitfalls of social media, particularly for lawyers who don’t fully understand how the different social media platforms actually work. There were also parallel sessions on a range of topics, including (as you might expect) law reporting and whether there might be too much of it: that was the topic on which Paul Magrath of ICLR and Dewey Cole of Newman Myers Kreines Gross Harris, PC compared the experience in England and Wales with that in the USA and in particular the State of New York, in a session entitled “Law reporting and public access in the courts: is too much a good thing?”

The conference ended with a handover of the presidential gavel from this year’s president, Dunstan Speight, librarian of Lincoln’s Inn, to Renate Ni Uigin, Librarian of King’s Inns. See you next year in Harrogate.

Homeward bound after a fabulous #BIALL2019 conference in 'sunny' Bournemouth. Thanks to all the speakers, sponsors, exhibitors and members. Already looking forward to Harrogate next year, but first sleep… pic.twitter.com/m3RlajHJ5n

— Jackie Hanes (@JackieHanes) June 15, 2019

Judiciary

French judges defy analysis

One of the most interesting discussions this author had at the BIALL conference in Bournemouth was with Antoine Dusséaux, co-founder of Doctrine, a Paris-based legal research and analytics platform. In particular, I wanted to understand better the story I had read about French judges objecting to the conduct of analysis on their judgment data and attempts to ban the practice (which is widely used in other jurisdictions as an aid to predicting litigation outcomes).

The problem began with a drive to make all case law easily accessible to the general public, thus improving access to justice and transparency. (Very creditable and something we would strongly support, though it remains a struggle this side of the channel.) The judgments were published as open government data, and therefore available for reuse. However, once some tech companies started doing analysis on the judgments, processing the data and using machine learning techniques to analyse it and draw predictions, it emerged that there were striking patterns of bias in the way judges were deciding particular types of case, notably immigration and asylum cases. Alarming discrepancies emerged: some judges had a very high asylum rejection ratio, while others from the same court had a very low ratio.

The judges complained via their union (something in itself surprisingly from a Common Law perspective) and a new law was passed, Article 33 of the Justice Reform Act, preventing anyone publicly revealing the pattern of judges’ behaviour in relation to court decisions. It provides, inter alia,

“The identity data of magistrates and members of the judiciary cannot be reused with the purpose or effect of evaluating, analysing, comparing or predicting their actual or alleged professional practices.”

The penalty is up to five years’ imprisonment. What is not entirely clear is whether it applies to any re-use, no matter the source of the judgments, or only to court decisions proactively published by the French government in open data. If the latter, it might permit someone who manually collected the judgments themselves to make an analysis.

Subject to that uncertainty, it seems the judgments will continue to be available and you can freely reuse the data, including the judges’ names, but you cannot aggregate data about particular judges and their patterns of behaviour. So if you do any analysis, you can’t identify the different judges being analysed, which means any comparison or predictions based on the data become meaningless.

However, it does prompt consideration of the use of anonymity in a more general sense in the reporting of what goes on in court. The anonymisation of the parties is uncontroversial in civil law jurisdictions (as is now mandated by the European Court of Justice in requests for preliminary rulings by natural persons) — what needs to be transparent is the system of justice, not the people caught up in it — and yet it feels like something that has to be justified, on grounds of privacy, to protect vulnerable parties or confidential information, in the common law world. By extension, what about the names of witnesses, or professionals who may be criticised (perhaps unfairly) for their actions or omissions in a case, or of the local authority or other organisation whose anonymisation cannot be justified merely on grounds of a risk of “jig-saw identification” of the vulnerable litigant parties? Again, in a common law context, such extended anonymisation needs to be justified, not routine. In a rather absurd case, press reports once complained that anonymisation had been taken “too far” when a judge’s name appeared to have been redacted from a case published on BAILII: see The curious case of the judge with no name (Transparency Project). It turned out the redaction was only to the HTML copy (not the PDF) and was in any event a technical glitch — nothing to see here!

The French judges’ insistence on shrouding their identity from algorithmic scrutiny may be justified on grounds of personal protection, which can also be in issue in our own jurisdiction. Recently a couple were jailed here for harassing a family judge about whom they had discovered a lot of personal information, some of it from social media, which they used to make credible and frightening threats against the judge and her family. (See Legal Futures, High Court rejects appeal by couple jailed for harassing judge.) But it seems harder to justify simply on grounds of protecting their reputation or that of the system as a whole, since this is probably better achieved by improving transparency and, perhaps, the process of appointment and training of the judiciary in the first place.

Further reading:

- Artificial Lawyer, France Bans Judge Analytics, 5 Years In Prison For Rule Breakers and The Judge Statistical Data Ban — My Story — Michaël Benesty

- Legal Week, France Bans Data Analytics Related to Judges’ Rulings

- ABA Journal, France bans publishing of judicial analytics and prompts criminal penalty

- Double Aspect, Justice in Masks (offering a Canadian perspective)

<Data> {Protection}

GDPR : one year on

Data Protection Regulation one year on: 73% of Europeans have heard of at least one of their rights, encouraging news.

However, only 3 in 10 Europeans have heard of all their new #dataprotection rights.

See the results of the Eurobarometer survey → https://t.co/qFb2bhb2dE#GDPR pic.twitter.com/IqxtLoLVah— European Commission 🇪🇺 (@EU_Commission) June 13, 2019

On 13 June, at an event to mark the first year of application of the EU General Data Protection Regulation, the European Commission published the results of a special Eurobarometer survey on data protection. The results show that 73% of respondents have heard of at least one of the six tested rights guaranteed by the General Data Protection Regulation. The highest levels of awareness among citizens are recorded for the right to access their own data (65%), the right to correct the data if they are wrong (61%), the right to object to receiving direct marketing (59%) and the right to have their own data deleted (57%).

In addition, 67% of respondents know about the General Data Protection Regulation and 57% of respondents know about their national data protection authorities. The results also show that data protection is a concern, as 62% of respondents are concerned that they do not have complete control over the personal data provided online.

The GDPR has been applicable since 25 May 2018. (Remember the panic and hyperbole to ensure compliance by the implementation date?) Since then, nearly all Member States have adapted their national laws in the light of GDPR. In the UK we had the Data Protection Act 2018. Among other things, this provided for the Information Commissioners Office or ICO to be the national data protection authority for the UK. Like other data protection authorities, it provides information and guidance on the new data rights and pursues and enforces penalties against those who infringe those rights.

Crime

Prisons and rehabilitation: new minister sets agenda

New justice minister Robert Buckland QC has set out his plan to ‘turn the tide on reoffending’ during his first keynote speech in the role. Buckland replaced Rory Stewart, who is currently making a bid for leadership of the Conservative Party (and, therefore, the government), as well as having the new job of Secretary of State for International Development.

Speaking at the Modernising Criminal Justice conference in central London on 11 June, Buckland called for a ‘whole system approach’ to criminal justice reform in which ‘prisons are one important constituent part, but by no means the whole story’. One of his key proposals is the abolition of short prison sentences and a “shift from custody to community” sentencing:

“In particular, it’s clear that short prison sentences simply aren’t working. Over a quarter of all reoffending is committed by those who have served short sentences of 12 months or less. They trap people in a cycle of crime that is very difficult to break out of. The result is more offending, more victims, more crime.

That’s why we think there is a case to abolish or further restrict the use of sentences of 6 months or less with some exceptions, and we hope to set out our proposals for consultation by the summer.”

Buckland inherits a department which has lurched from crisis to crisis, on prisons and probation — the latter subject to a recent reversal of the disastrous part privatisation ushered in by former Lord Chancellor Chris Grayling. His predecessor had offered to resign if violence did not reduce in ten key prisons — a promise that does not appear to have been assigned to his successor, but we shall see.

On the same date, the Justice Committee of the House of Commons welcomed the government’s response to its report Prison Population 2022: planning for the future — Report Overview but said ministers (see above) have “failed to commit to a sufficient plan of action to effectively tackle the crisis faced.”

In April, the Committee had concluded, at the end of an 18-month inquiry, that the Government’s current approach to prisons was inefficient, ineffective and unsustainable in the medium or long-term. Among a range of recommendations, it set out why there should be a presumption against sentences of six months or lower and argued that the Ministry of Justice needs to focus on ensuring safety and decency in prisons is maintained, as well as improving rehabilitation of offenders when they leave prison.

The Government Response agreed with the premise of many of the Committee’s recommendations but offered little in terms of action in addition to what has already been announced, according to the committee. However, as the minister’s speech shows, the Government has acknowledged that there is a strong case for abolishing short sentences. The chair of the committee, Bob Neill MP commented:

“There is more to be done to ensure we have the transparency needed to have a proper debate about the role prison should play.

We will continue to press for investment in rehabilitation services that work, and better access to support and opportunities for offenders which would reduce repeat imprisonment, alleviate pressures on jails and save public money.

This should be happening now, not at some unspecified point in the future.”

Dates and Deadlines

Journalists and legal bloggers attending family courts — A Workshop for lawyers [reminder]

St John’s Chambers, 101 Victoria Street, Bristol — 25 June 2019, 17:00–19:30

In light of the Legal Blogging Pilot implemented through PD36J, The Transparency Project are running a CPD workshop for lawyers interested in brushing up their ‘transparency’ knowledge — whether with a view to taking part in the scheme themselves, or so they feel better prepared for responding to attendances by legal bloggers or journalists in cases where they are instructed. Click here for booking information.

LAG Community Care Law Conference 2019

39 Essex Chambers, Chancery Lane, London — 4 July 2019, 09:15–17:15

The LAG Community Care Law Conference 2019 brings together leading experts to provide up to date guidance on legal and policy developments in community care law. It will cover recent case-law and legislative changes, guidance on the new Liberty Protection Safeguards, how to interpret eligibility criteria and, importantly for all practitioners working in this area, how to challenge cuts.

Booking details via Eventbrite.

And finally…

Tweet of the Week

is from a judge on Ingham County Circuit Court, in Michigan, and demonstrates the rather different role of the US judiciary, both in communicating directly with the public they serve (via social media — something discouraged in England & Wales) and in performing wedding ceremonies (though not all states may be the same in this regard).

11years ago I sentenced him amid a raging heroin addiction. One week ago I performed his marriage ceremony after 10 years clean. Every life holds this potential. pic.twitter.com/g7yKU34ZiF

— Joyce Draganchuk (@JudgeJoyceD) June 16, 2019

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading. Watch this space for updates.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.