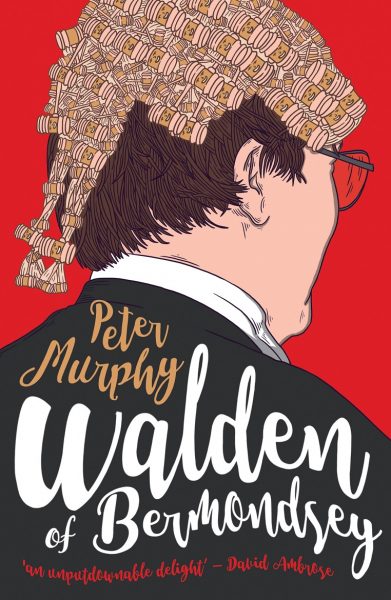

Book review: Walden of Bermondsey, by Peter Murphy

Reviewed by Paul Magrath His Honour Judge Walden is the resident judge (RJ) at Bermondsey Crown Court. This means that as well as conducting an unusually interesting variety of cases, he has to manage the court staff and facilities, and juggle the lists to ensure a fair distribution of work to his judicial colleagues –… Continue reading

Reviewed by Paul Magrath

His Honour Judge Walden is the resident judge (RJ) at Bermondsey Crown Court. This means that as well as conducting an unusually interesting variety of cases, he has to manage the court staff and facilities, and juggle the lists to ensure a fair distribution of work to his judicial colleagues – all the while fending off the depredations of the penny-pinching Grey Smoothies from the Ministry of Justice.

Or, as he puts it himself, “the RJ’s main role is to be the person to blame whenever something goes wrong.”

Although he benefits from the moral support of his wife, the Reverend Mrs Walden, of whom he is slightly in awe, he is equally concerned not to put a foot wrong in the eyes of the tabloid press: “if you do something really stupid,” he says, “you automatically become a ‘Top Judge’.”

A “TOP JUDGE” WRITES…

Judge Walden is the comic fictional creation of Peter Murphy, himself a former circuit judge who was once RJ at Peterborough. But I’m willing to bet that none of the cases he tried there in real life was half as interesting or as much fun as the six described in these stories. They deal with a range of crimes, including arson (the burning down of a church), assault (by one election candidate on another), impersonating a solicitor, art fraud, sovereign immunity (by someone claiming to be the king of an uninhabited small island) and the running, above a perfectly respectable restaurant, of a brothel.

Mixed up with each case is another episode in the life of the court staff. This might be the problem of getting the Grey Smoothies to fund a secure dock (to prevent an irate defendant escaping or jumping out and assaulting someone) or persuading them not to shut down the court canteen. Or it might be the entertaining spectacle of a High Court judge, more used to planning or chancery matters, struggling with the evidential complexities of a simple offensive weapon case.

Usually it is these admin matters, rather than the cases themselves, which threaten to spoil the “oasis of calm in a world of chaos” that is the lunch hour in the judicial mess, where Charlie Walden and the other judges sit round an oversized table discussing their cases and picking each other’s brains over sentencing options. They include Judge Rory “Legless” Dunblane, who favours a “robust” approach to sentencing (in spite of whatever the guidelines say); Judge Marjorie Jenkins, a commercial silk “supermum”, who has taken up judging by way of a career break; and Judge Hubert Drake, of indeterminate age, who’d rather be dining at the Garrick. As for Walden himself, though he often feels a bit embattled, there are few setbacks that can’t be ameliorated – or triumphs celebrated – by a trip to La Bella Italia for some delicious pasta and a bottle of Chianti shared with his wife.

Through Walden’s eyes, we see the criminal justice system for what it is – a bit of a muddle, and only as good or bad as the humans who do their best to manage it. Yet in spite of all that fate and the Grey Smoothies can throw at him, Judge Walden manages to deliver justice. Though his exasperation is sometimes palpable, what triumphs over everything is his sense of humour. And it is the humour that makes Walden of Bermondsey such a delightful read. Think of him as what Rumpole would be like if he ever became a judge, and you get some idea of his self-deprecating wit and indomitable stoicism. Add a dash of Henry Cecil for his situation and AP Herbert for the fun he has with the law, and you get a sense of his literary precedents. Nevertheless, Walden’s is a unique new voice, which we hope has many more tales to impart, from his busy Bermondsey courtroom.

Just to get it on the record

Each of the six stories in this volume is presented in the form of a diary, written by the judge in the quiet moments of the working day or relaxed evenings at home, over the course of his hearing of a particular case. In one of them he has to direct the jury on whether insults shouted by two parliamentary candidates when resorting to fisticuffs on election night – one calls the other a “toffee-nosed, upper class git”, the other retorts with “moronic, working class lout” – mean that their assaults were racially aggravated. Can social class be categorised as membership of a particular racial or religious group? Should he direct the jury on the meaning of the relevant statute? He decides in the end to leave the matter to their common sense.

In another he must consider whether someone who claims to have invaded an unoccupied island in the English Channel, and duly declared himself the king of it, is entitled to plead sovereign immunity against charges of fraud, money laundering and possession of criminal property.

Possibly the most awkward case is the one where Judge Walden is forced into a situation where he must appear to ask an embarrassingly naïve question, purely to ensure that the answer gets on the record. The classic example is the judge who once asked “Who are the Beatles?” and was “instantly derided in the press as the typically remote, out of touch and pathetically outdated male all too commonly found on the bench”. Yet he was probably just trying to get the answer on the record.

Fearing that it will lead to a ‘Top Judge’ moment, Walden nevertheless proceeds, as he must, in the interests of justice:

‘Mr Drayford,’ I say, ‘would you care to establish from the Inspector the nature of the item shown in photograph fifteen.’ …

The Inspector makes a pretence of studying it closely.

‘It appears to be a vibrator, your Honour,’ he replies.

He is not going to elaborate without being pushed, so the moment arrives.

‘What is a vibrator?’ I ask.

Walden of Bermondsey (No Exit Press, £8.99 paperback) is being launched today, 5 December 2017, at Middle Temple, at 6.30 to 8.30 in the Queen’s Room. You can get tickets at the door for £15, which includes a signed copy of the book, and a chance to meet the author.