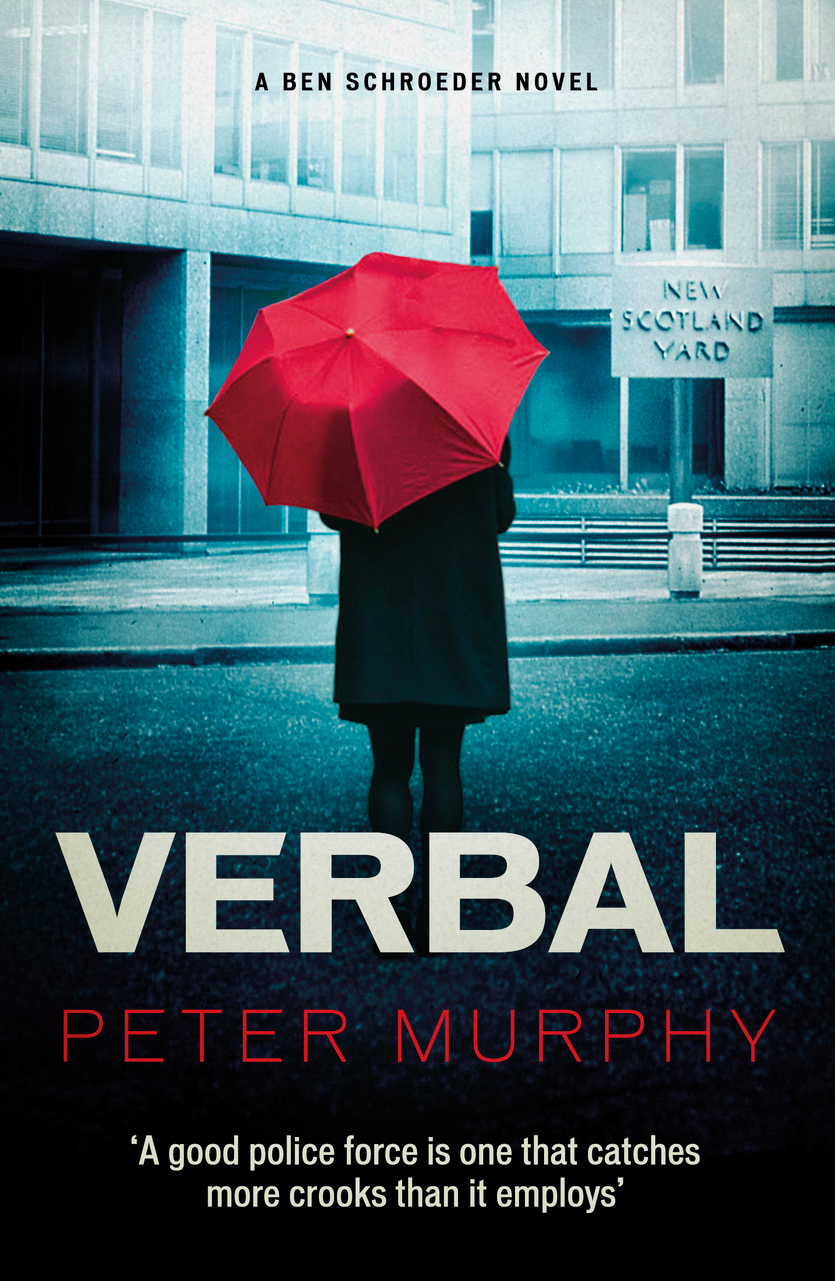

Book review: Verbal, by Peter Murphy

Paul Magrath reviews the latest courtroom thriller from Peter Murphy, in which barrister Ben Schroeder deals with a case involving spies, drug dealers and high level police corruption.… Continue reading

Regular readers of this blog will be aware that author Peter Murphy has created in barrister Ben Schroeder a character whose adventures in and out of court hold a mirror up to life at the bar in the 1960s and 70s. As well as overcoming class prejudice and antisemitism in gaining a place in chambers and developing his practice in the early days, he has also been engaged, over a series of six previous novels, in cases that highlight major legal problems and developments. These include the death penalty, nationalist terrorism, sexual abuse in religious schools, the Cambridge Soviet spy ring, and a gambling associate of Lord Lucan who, like him, absconds from justice. (And just happens to be a High Court judge.)

We have now reached the early 1980s and Schroeder, who has recently taken silk, is dealing with a case involving high level police corruptions. As the title indicates, this includes the practice of “verballing” suspects, ie fitting them up with faked confessions to crimes which they may or may not have committed, but for which the police have insufficient other evidence on which to charge. It also includes officers taking “drinks” or bribes, to make charges “go away”; and undercover officers moonlighting as the very crims they have been set to catch, in this case international drug dealers.

The case is complicated by the involvement of that absconder from justice in one of Schroeder’s earlier cases, now living under cover in Yugoslavia, and the security services, who happen to be investigating a mysterious death in the same city, Sarajevo. Could this all be related to the activities of the international drug dealing cartel which the police now claim to have cracked?

In court, Schroeder cross examines the officers whose evidence against his client may turn out to be even more damning against themselves; while out of court, he must face the chambers politics and professional resentment that have dogged him since his pupillage. As you’d expect, he emerges triumphant. But although you can’t fault Murphy for legal and procedural authenticity, I felt at times the bent coppers gave him an easier run than might have been the case in real life. Although Schroeder makes the point in cross examination, the idea that the defendant, a well heeled Cambridge graduate of English literature would have yelled at the officers (as they claimed in their collaboratively compiled notes) in Cockney cant (“bang to rights” an’ all) seems almost too conveniently absurd, and makes them look more than a little clownish. (That said, I have since been told the police became so blasé about the process that they stopped considering whether their verbals had the ring of authenticity, or assumed a jury wouldn’t notice.)

I felt a pang of nostalgia when Murphy described the Lamb pub in Lamb’s Conduit Street as the venue for the undercover encounters, not just because the whole idea of standing in a crowded pub drinking beer is currently so impossible but also because it’s where I first met him, soon after the first Schroeder book. Schroeder was a pupil then. Now he’s made head of chambers. It’s been quite a journey.

For extra CPD points, there is an afterword explaining the true history of police corruption and the common abuses of suspect interviews, which were cured in turn by a major external police investigation and by the enactment of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. This came into force in January 1986 and remains in force to this day, requiring police interviews to be conducted at a police station and to be recorded. Thanks to this, says Murphy, who recalls it from his own practice at the bar at the time, “verballing” is now largely a thing of the past.

Verbal, by Peter Murphy (No Exit, £8.99)

Featured image: Gower Street at night, via Shutterstock.