Book review: The UK Supreme Court Yearbook, Vol 10 (2018-2019), and Spider Woman by Lady Hale

The Prorogation Case of 2019 forms both the centrepiece of the latest Supreme Court Yearbook, and the climax of a glittering legal career for the court’s president, Lady Hale, whose autobiography Paul Magrath reviews alongside… Continue reading

It takes time to produce the UK Supreme Court Yearbook and volume 10, which covers the years 2018-2019, only emerged in the latter part of 2021. It is, however, a particularly significant volume, looking back over the court’s first decade and reviewing the year in which it made what must be its most significant decision: R (Miller) v Prime Minister [2019] UKSC 41; [2020] AC 373 (the ‘Prorogation Case’).

That was the case in which Lady Hale, the court’s president achieved quasi-celebrity status, not for her calm management of the hearing or her diplomatic skill in arriving at a clear, unanimous and definitive judgment in such a controversial case… but for wearing, as she delivered the court’s televised judgment summary, a glittery spider brooch. In her foreword to the Yearbook she claims to regret the distraction this caused. But that does not seem to have stopped her, somewhat cakeishly, calling her autobiography Spider Woman.

The Yearbook

The Yearbook’s editor-in-chief, Dr Daniel Clarry, and its chief technology officer, Dr Sidney Richards, weigh and measure the apex court’s throughput in “A Quantitative Review of the UK Supreme Court’s First Decade”. While much of this might be strictly for the trainspotters, their analysis does yield some interesting observations. They note, for example, that “Judgments are becoming noticeably shorter over time, with proportionally fewer divided judgments and more unanimous judgments.” That trend is likely to please the official law reporters. However, what appears to be a “conscious effort to achieve greater unanimity” comes at a cost: judgments are taking longer to deliver. “The time elapsed from hearing to judgment has doubled over the Supreme Court’s first decade.” That trend was bucked in the Prorogation Case, though, the 11-strong bench’s unanimous judgment being compiled over barely more than a weekend, with a nailbiting urgency well captured in Hale’s book.

As in previous volumes of the Yearbook, there are introductory essays examining the court’s role in terms of national and international jurisprudence and the legacy of its decision making in the overall development of the law. And there are chapters by leading practitioners and academics examining developments in particular areas of law, by reference to the cases on those topics that came before the court over the course of the year.

But this year’s volume also contains a substantial middle section devoted entirely to the Prorogation Case and the constitutional implications both of the ruling itself and of the court’s role in deciding it.

The Prorogation Case

The section begins with a piece by the star advocate, Lord Pannick QC, himself no stranger to legal Twitter celebrity (with a Billable Hour T-shirt to prove it). His article acknowledges his role as lead advocate for the lead claimant, Mrs Gina Miller, but the piece is a wider discussion of the background and implications of the case. It was, he says,

“both an orthodox application of basic principles of our constitutional law and a remarkable assertion of judicial independence to protect our constitution from an unprecedented – at least in modern times – abuse of prime ministerial power.”

Though the subject is technical, his writing is often colourful. He compares the way the Speaker of the House of Commons ordered the record of the unlawful prorogation to be expunged, after the court’s judgment, to “the episode in the 1980s television series Dallas which revealed that the previous series in which Bobby Ewing had died was just a bad dream”. Discussing the case itself, he says:

“The Government’s counsel, Sir James Eadie QC and Lord Keen QC, displayed their customary skill at dispensing forensic perfume, but even they could not conceal the stench of unconstitutionality coming from 10 Downing Street. As Lady MacBeth lamented, ‘all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand’.”

The byline to this piece notes that “The views expressed are those of the author alone”. But many of his readers will no doubt share them.

There follow a number of essays by academics. First, there is one by Professor John Finnis criticising the court’s decision, principally on the grounds of non-justiciability and constitutional convention, and then one by Professor Paul Craig defending it against that criticism. Both are based at Oxford and I hope they will not be offended if I don’t insult their erudition by attempting a summary for which I am singularly ill equipped. Both also appear to be rehearsing or refining arguments already made in other fora, in much the same way that counsel refine their submissions on appeal to a higher court, all of which seems rather appropriate in an apex court’s yearbook.

Further defence of the decision comes from Professor Alison L Young, of Cambridge, followed by Professor Anne Twomey, of the University of Sydney, Australia, who considers among other things “How might such issues be dealt with in Australia?” We then move from New South Wales to Old North Wales, as Mr Justice (Michael) Fordham, as he now is, contributes an essay from his perspective as lead advocate for the Counsel General for Wales, third intervener in the Prorogation Case. He makes the point that the case affected the UK as a whole but also had implications for and required the participation of all the devolved nations. By the same token there is also a piece from John F Larkin QC, Attorney General for Northern Ireland. (Though he wasn’t an intervener, one of the other interveners in the case was Raymond McCord, a victims’ campaigner concerned about the consequences of prorogation decision on the Good Friday Agreement.)

Another intervener was the former Prime Minister, Sir John Major, whose counsel, Lord Garnier QC, with perhaps unnecessary modesty, titles his contribution “Some musings from the edge of the court”. This section ends with an article by Professor Cheryl Thomas of UCL asking “Is the Prorogation Case the UK Supreme Court’s Marbury v Madison: what makes an institution-defining case?” The short answer is, of course, no. Marbury v Madison (1803) 5 US (1 Cranch) 137 could be described as the US Supreme Court’s supreme power-grab case, cementing its future role in the constitutional power balance of the USA. The essay is really about speculation over the UK apex court’s future role and suspicions of judicial activism and over-reach.

Although that ends the formal section dealing with the Prorogation Case, one of the topical essays in the final section deals with Constitutional Law, and is written by Aidan O’Neill QC who was counsel for the respondents in the government’s appeal in Cherry v Advocate General for Scotland (Lord Advocate intervening), joined with Miller 2 in the Prorogation Case hearing. Though not entirely focused on it, the article discusses the case alongside other cases of constitutional significance.

Spider Woman

While there is much to marvel at in Brenda Hale’s list of achievements, this Spider Woman has no need of the superpowers of her comic book namesake. “Equal to anything” is her motto, and though the other judges were anxious about her “agenda” when she first joined the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords in 2004, she seems to have been a fairly traditional feminist of the kind who simply sees no reason why being a woman should be any bar to her doing just as well as a man in any professional role. That’s not to say she always had a man’s sometimes unwarranted confidence. Right at the start of the book she confesses to repeated bouts of imposter syndrome, while also revealing a slightly mischievous iconoclasm:

“This is the story of how that little girl from a little school in a little village in North Yorkshire became the most senior judge in the United Kingdom. How she found that she could cope. And how all those other people who feel they are imposters can learn to cope too. Some of them may even be men.”

Although she first thought of her book as “a conventional lawyer’s memoir, written mainly for people who were already lawyers and people who might be thinking of becoming lawyers” , Hale says she was helped by her editor and publishers to address a “much broader readership”. The writing is certainly much less technical and academic than the essays in the Yearbook to which she contributes a foreword. Even so, she loves talking about her cases, and many chapters begin in a general autobiographical way, with personal events and reminiscence, only to dive down a rabbit-hole of case law and legislation a few pages in, from which they only emerge towards the end of the chapter. It is still much more of a legal biography than the biography of someone who happens to be a lawyer.

The story takes her from that little school in Yorkshire to the big university in Cambridge, to a career at the Bar which soon gave way to the lure of academic life, then a stint as the youngest ever (and first woman) Law Commissioner, before embarking on a judicial career that went, as it were, from High to Mighty. When she was appointed a High Court judge in 1994 (having confidently refused a place on the circuit bench) she was only the tenth woman ever to occupy that position (and this was 75 years after the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919). Although she was known as Lady Justice when promoted to the Court of Appeal, she was called a Law Lord (or Lord of Appeal in Ordinary) as the first (and only) woman to be appointed to the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. After the House of Lords became the UK Supreme Court, she went on to become its first woman President. If imposter syndrome did ever trouble her, it doesn’t seem to have got in the way of a career of great and varied success.

Constitutional battles

As a student, she was inspired to read law by her studies of 17th century history and the constitutional battles of kings, courts and Parliament. As a judge she “relished having to decide a point of law” which is why she would accept nothing less than a place on the High Court bench, or above, where “the law is made”. She thinks her stint as a law teacher helped her write clear, accessible judgments. But there were aspects of the job she disliked, such as the wearing of wigs, the endless rambling speeches on call night at her Inn (Grays) and the fusty formality of dinners on circuit where, even in the 1990s, ladies were expected to leave the table to the gentlemen after dinner (a convention she deliberately broke when she had the chance).

In answer to her fellow Law Lords’ anxiety, she observes:

“It is strange that challenging the male-dominated status quo in the law and the legal profession is seen as an ‘agenda’ whereas preserving it is not. We have seen how efficiently the protectors of the status quo can mobilise when they feel it under threat – for example, by meeting calls for diversity with the mantra of ‘merit’. But mostly they have no need to be so vocal – so that agenda remains hidden and, no doubt for many, quite unconscious.”

On the other hand, her mould-breaking feminism does not prevent her criticising the first woman Lord Chancellor, Liz Truss, over her abject failure to live up to her oath to protect the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary, when the Daily Mail savaged three High Court judges after their decision in the first Miller case. “It would have been so easy,” says Hale, helpfully drafting the form of words Truss might have used. It’s as though Truss has appeared before her as a less than promising student, whose essay is frankly not up to scratch.

As for that spider, in her foreword to the Yearbook, Hale explains:

“Regular viewers know that I often wear a brooch – usually a creature – to liven up our normally quite sober dress but that it has no obvious connection to the matter in hand. … There was no hidden message in the brooch I wore that day, but perhaps I should have foreseen that the public and the media would look for one.”

They did indeed. One of the most bizarre suggestions was a reference to a song by The Who called “Boris the Spider” (who comes to a sticky end).

In the end such speculation is rather silly, but Hale does not seem to mind the extra publicity it may have generated; just as she seems quite happy to have been called “the Beyoncé of the legal world” (by Legal Cheek). If it brings more readers, if it draws attention to the judgments, if it upsets a few stuffed shirts, well perhaps that’s all to the good.

Daniel Clarry (ed), The UK Supreme Court Yearbook, Vol 10: 2018-2019 Legal Year (Appellate Press, £120).

Lady Hale, Spider Woman: a life (The Bodley Head, £20)

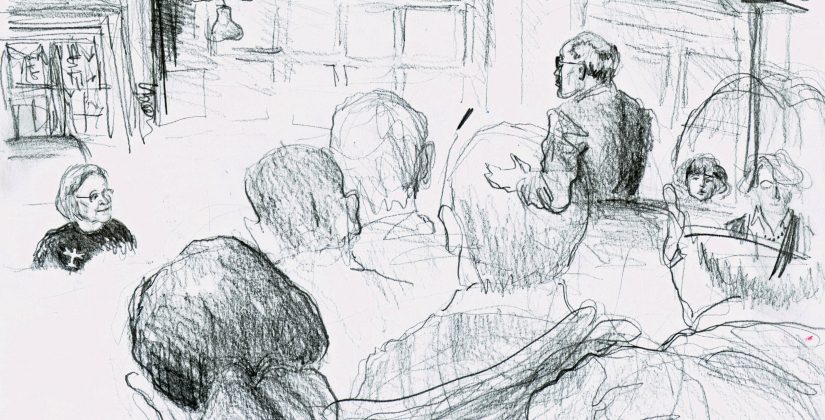

Featured image: “The Prorogation Case” by Isobel Williams (from the Yearbook, reproduced with thanks)