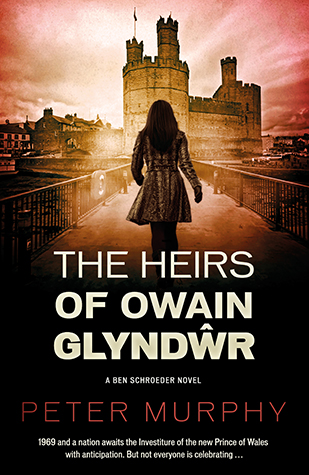

Book review: The Heirs of Owain Glyndŵr by Peter Murphy

Paul Magrath reviews a mesmerising new courtroom thriller in which Peter Murphy’s ambitious barrister hero Ben Schroeder takes on a challenging case involving a Welsh nationalist bomb plot. All the details of barristerial life, the rules of ethics and evidence, and the courtroom procedure appropriate for the 1960s period setting are pitch perfect. Yet is… Continue reading

Paul Magrath reviews a mesmerising new courtroom thriller in which Peter Murphy’s ambitious barrister hero Ben Schroeder takes on a challenging case involving a Welsh nationalist bomb plot.

All the details of barristerial life, the rules of ethics and evidence, and the courtroom procedure appropriate for the 1960s period setting are pitch perfect. Yet is also raises very contemporary questions about the roots of radicalism, the motivation for terrorism and the conduct of the security services in combatting it.

They say hard cases make bad law. But hard cases also make good barristers, and none better than Ben Schroeder, the ambitious young hero of Peter Murphy’s growing series of legal thrillers, for whom each new case brings both greater challenges and greater rewards.

This is now the fourth novel in the series charting Schroeder’s career as a barrister in the 1960s. In earlier volumes he’s sallied forth from his chambers in London to defend clients charged with sexual offences, murder, and espionage. This time his client is charged with terrorism. Contemporary as this may sound, we are a long way from Belmarsh and the fatal lure of radicalised Islam. We go back to a time before even the futile boom of belligerent Irish nationalism and the anarchist cells of the continental counterculture that so disfigured the 1970s. The terrorists on this occasion are Welsh nationalists, outraged that the Anglo-German queen’s eldest son and heir to the throne is to be imposed on them as the Prince of Wales, and determined to put a stop to it.

Anyone old enough to recall the 21-year-old Prince Charles’ investiture as Prince of Wales at Caernarfon Castle in July 1969 will know that the bomb plot masterminded by a secret cell of the organisation known as the Heirs of Owain Glyndŵr did not succeed. No bomb went off at the castle, and the ponderous ceremony in which the awkward young prince was robed in flattery, crowned in pomp, and mouthed a few words of recently-learned Welsh alongside the formal English, was watched by millions – most of them in black and white but a good many on their newly acquired colour TVs.

This book tells the story of how the plot was hatched, after the new owner of a Welsh language bookshop falls in with a group of ardent nationalists. Schroeder’s client is the wife of the bookshop owner. She was never supposed to have been involved, but something goes wrong, she gets arrested as the driver of the car in which the home-made bomb is found before it can be planted at the castle on the night before the investiture, and despite her protestations that she knew nothing of the contents of the package her brother’s best friend had placed in the boot of her car, she is charged with conspiracy to cause explosions.

Can Ben Schroeder save her from prison and separation from her child? Much of the narrative takes place in court, where law geeks will be pleased to note, inter alia, that the admission of police interrogation evidence (a key aspect of the story) is correctly governed by the common law Judges’ Rules which held sway until the enactment of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act in 1984. But this is no more than you’d expect from the author of Murphy on Evidence.

Peter Murphy read extracts from the book at a launch party this week in the library of Middle Temple, of which he is a member. He explained his interest in the subject matter and in Welsh history generally by reference to his own genealogy: although his father’s family (and the Murphy surname) came originally from Cork in Ireland, on his mother’s side the family is Welsh. Peter began the evening with a warm Welsh welcome and there are bits of Welsh in the book.

He also explained that, although the plot in the book ultimately fails, there were a number of other bombs plots and at least one fatal explosion targeted at the royal investiture, though the royal family members were reportedly never in any serious danger.

As for Ben Schroeder, part of the point of the series was to show how someone who didn’t fit the mould – who hadn’t been to the right sort of school or university, and came from an East End Jewish trading family – was nevertheless able to overcome the obstacles to join the Bar and flourish. This was a time when the Bar was far less diverse than it is today, when it was rare to see women barristers or those from ethnic minorities.

I’ve enjoyed all Murphy’s books and you can find them all reviewed on this blog – just type “Murphy” into the search field at the top of the page. You’ll also find a comment on his widely reported ruling in the so-called “Niqab” case: until his recent retirement, His Honour Peter Murphy sat as a judge in the Crown Court and was resident judge at Peterborough. So he knows what he’s talking about, and his courtroom scenes are rooted in realism, not the gavel-tastic melodrama of some overheated television serials. Fans of his writing, among whom I count myself a member, will be pleased to know that there is another Ben Schroeder novel on the way. So watch this space.

Paul Magrath is Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR. He tweets as @maggotlaw.