Book review: Mr Justice McCardie (1869-1933) – Rebel, Reformer, and Rogue Judge

Antony Lentin’s life of Henry Alfred McCardie, published in the centenary year of his appointment to the High Court Bench, offers a fascinating portrait of a judicial figure whose reforming judgments have stood the test of time rather better than some of the public pronouncements that brought him fame and notoriety in his own day. … Continue reading

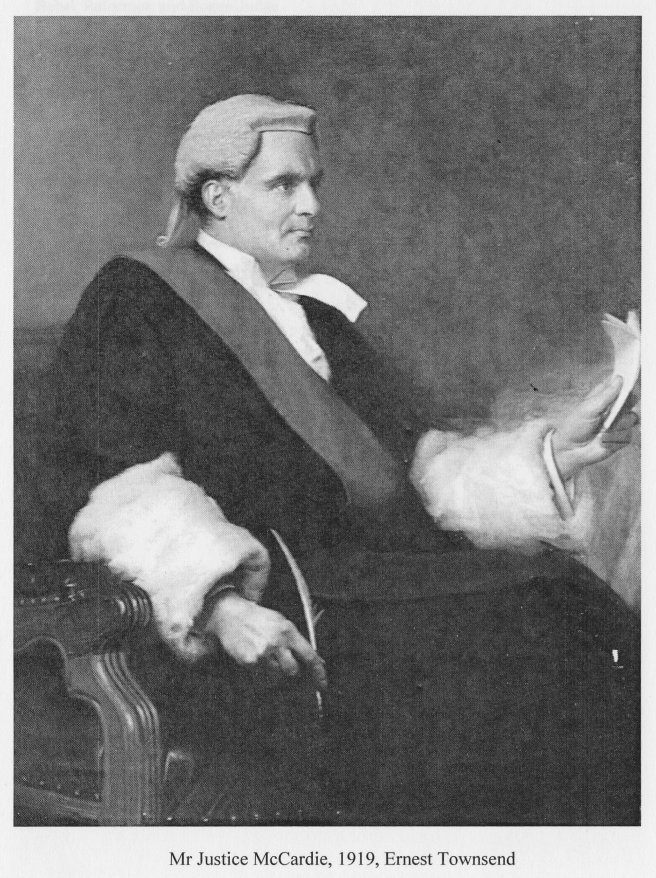

Antony Lentin’s life of Henry Alfred McCardie, published in the centenary year of his appointment to the High Court Bench, offers a fascinating portrait of a judicial figure whose reforming judgments have stood the test of time rather better than some of the public pronouncements that brought him fame and notoriety in his own day. Review by Paul Magrath

Mr Justice McCardie (1869-1933) – Rebel, Reformer, and Rogue Judge

Mr Justice McCardie (1869-1933) – Rebel, Reformer, and Rogue Judge

By Antony Lentin (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, £61.99)

Delving in the law reports of yesteryear for precedents that still chime with a modern view of the law, one of the names one might expect to turn up is that of Mr Justice McCardie.

In his day, a fellow judge described him as “a law reformer of outstanding courage and clear vision” and the Law Journal declared that “no present-day figure on the Bench is of greater interest than Mr Justice McCardie.” He was compared to the US Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis in his conviction that judicial decision-making should be guided not only by precedent but also by its relevance to changing social realities.

But all too often with the rulings and dicta one stumbles upon in the course of legal research, the character of their originator remains a closed, or even unwritten, book. Not so McCardie J. Having sketched his life for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Professor Antony Lentin, barrister and Senior Member of Wolfson College, Cambridge, has now fleshed out the portrait with a full biography. Though something of a cautionary tale, this is a fascinating book about a fascinating man.

Controversialist-at-law

As this book’s sub-title, complete with Oxford comma, indicates, McCardie was a turbulent figure on the legal landscape of his day. His respect for the common law he knew so deeply was unbounded, but it also prompted him to correct and develop its golden threads to meet the needs of the modern day. As a reformer, a bit like Lord Denning, he had both his champions and his detractors – both within the legal world and without it.

He turned down the chance to become an MP, where his reforming zeal might have come up against a different kind of opposition; but he also turned down the chance to take silk – though not having KC after his name proved no bar to a seat on the High Court Bench. Higher judicial office was, however, denied him, no doubt because in the end he was too much of an awkward customer.

As a law reporter, I rather like the way each chapter begins with a set of “catchwords”. Chapter Four, which comes at the height of his fame, is headed:

McCardie –reading and art—lecture as Middle Temple Reader—sociology—supports women’s rights—women jurors—McCardie’s celebrity—actions for breach of promise—inequality of husbands and wives—McCardie and publicity—eugenics—controversial pronouncements and public reactions—cuts in judicial salaries—McCardie’s protests—objects to ‘slavery of caselaw’

This seemingly random collection of themes rather aptly epitomises the man himself and the breadth of his interests. He had an unconventional entry to the law, having left school at 15 and not gone to university, instead working for a while at an auctioneers and in various business ventures until, at the age of 21, he joined Middle Temple as a student and entered chambers in Birmingham. But having settled on the Bar, he was determined to make a success of it.

A fearless advocate

His practice coincided with the golden age of histrionic advocacy – exemplified by such practitioners as Marshall Hall and FE Smith – and although McCardie’s style was less bombastic he shared with them a fearlessness in the face of judicial overbearing. Unlike Marshall Hall, who confessed himself no great legal brain (“I’m an advocate not a lawyer” he insisted), McCardie took a huge intellectual interest in the law itself.

His first visit to the library in Middle Temple as a student had proved life-changing: “I stood, as it were, on the shore of a broad ocean of learning”, he later wrote, realising “the magnitude of the legal material that lay around me”. He became a voracious reader of law reports, both English (which would then have included cases from around the Empire) and American (their common law sharing a common ancestry). He was widely read in other fields, too, such as science and history. (Apparently his books would be kept in heaps on the furniture in his flat, because his walls were covered in the water colours he collected, to the exclusion of any space for bookshelves.)

The law reports were full of McCardie’s annotations. His judgments and lectures were full of their citations, many of them memorised by him. In time the law reports included his own cases, of course, but the noter-up slips would also have recorded their more than occasional reversal by the Court of Appeal.

McCardie v Scrutton

As to that, one of the more extraordinary judicial spats in which McCardie became involved was with Lord Justice Scrutton, best remembered now as the author of the practitioner’s bible On Charterparties, but with a temper and temperament that did nothing to endear him either to the bar or to more junior judges. In an extraordinary exchange of correspondence with the Master of the Rolls of the day, McCardie sought to insulate his own judgments from the scrutiny of Scrutton – if necessary by withholding his notes in any case going to an appeal court bench on which Scrutton LJ might sit—to no avail.

What annoyed Scrutton and other judicial figures was McCardie’s activism – his refusal simply to apply the common law as he found it, and instead, by creative extension of existing precedents, to develop the law in ways he thought appropriate for the changed circumstances of contemporary life.

McCardie was ahead of his time in calling for an end to absurd doctrines in matrimonial law such as “connivance”, “condonation” and “collusion” and torts such as “loss of consortium” and “enticement”, which were only finally swept away in the 1960s, and in his approach to the law on insanity and diminished responsibility for murder. But his support for eugenics and the compulsory sterilisation of the “mentally defective” seems rather less progressive now than it would have done in his day, when it was intellectually quite fashionable. (See, for example, John Carey’s The Intellectuals and the Masses (1992).)

The “bachelor judge”

By the mid-1920s, McCardie was by far the best known judge on the Bench. By the end of the decade, he was able to hold a press conference in his room at the Law Courts where, according to Time Magazine, he “amiably delivered himself of a little seasonal philosophising”. He became known as “the bachelor judge”, standing up for women’s rights and displaying an uncommon knowledge of women’s garments, it seems, without ever having been married himself. “A bachelor is a man who looks before he leaps,” said McCardie, “and having looked, does not leap.”

As to that, there is something of a surprise in store for the patient reader. Though the papers never revealed the fact until after his untimely death, the so-called bachelor judge had more than a passing acquaintance with more than one married woman. He even had a son. Was it the threat of disclosure of his scandalous love life, his secret gambling addiction, or his own professional disappointment, that caused him to bring both career and life to an end in the same, self-administered gunshot? But the fact that he killed himself in apparent despair should not blind us to the contribution McCardie made to the common law, and the value of his legacy in the judgments that live on in the law reports of his cases.