Inheritance disputes and the media: making wishes come untrue

In this guest post, Barbara Rich explains how the Daily Mail missed an opportunity to explain the essential rights of a cohabitant to ask the court to make reasonable provision for her under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975, rather than describing the case as a judge simply overturning the deceased’s wishes… Continue reading

In this guest post, Barbara Rich explains how the Daily Mail missed an opportunity to explain the essential rights of a cohabitant to ask the court to make reasonable provision for her under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975, rather than describing the case as a judge simply overturning the deceased’s wishes and fulfilling hers.

The Daily Mail often gives prominent coverage to cases about inheritance disputes — so much so that some of my colleagues sometimes refer to them as the “Daily Mail Law Reports”. Inheritance disputes which lead to trials and published judgments are subject to the general principle of open justice, so all the evidence is heard and judgment given in a court open to the public, and can be reported in the media. A successful newspaper knows what interests its readers, and post-death stories of broken promises, disappointed hopes and unearthed secrets interest a lot of people, as Victorian novelists knew.

Sometimes these newspaper accounts convey the depth of human interest and variety of personalities in these stories extremely well. And they provoke strong reactions from below-the-line commentators, who are quick to speculate and extrapolate from the reported facts, and to express their own judgement on the characters of the cast of living and dead protagonists, and on the moral rightness or wrongness of the terms of a will or of the court’s judgment in an inheritance dispute. This is cautionary material for future litigants, who, having read below the line, may understandably dislike the idea that their own case will be subject to the same sort of vehement public dissection. On the other hand, media coverage can make people aware that they may have a valid inheritance claim, when it might not otherwise have occurred to them.

Does a story of an inheritance dispute in a popular newspaper do anything for the desirable objective of public legal education, in the sense of helping people understand the legal system and how judicial decisions are made, beyond raising this kind of awareness? A recent example sharply illustrates some of the ways in which it fails to do so.

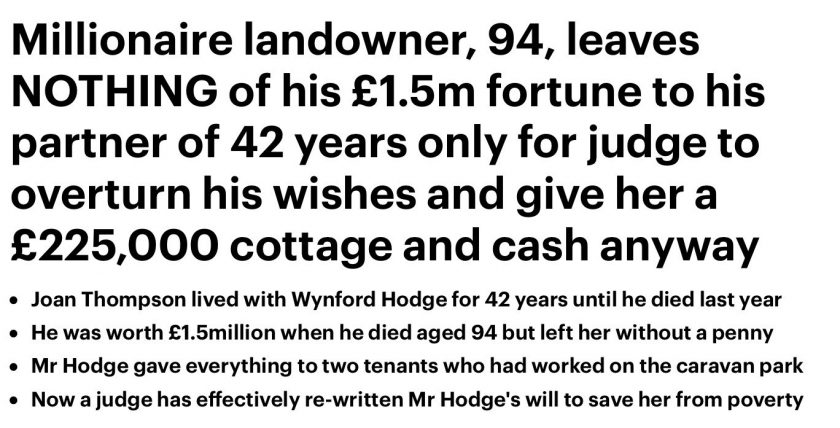

In this story, Wynford Hodge, a man who died at the age of 94, leaving an estate worth £1.5M containing a farm and several other properties in Wales, disinherited Joan Thompson, his partner of 42 years, “only for judge to overturn his wishes and give her a £225,000 cottage and cash anyway”. The Daily Mail (in an article with a hypertext link inaccurately referring to a “widow” and a “husband”, and which has attracted over 1,000 below-the-line comments) described Wynford Hodge as a “wealthy businessman”, which in a sense was true, but was perhaps a description that neither he nor Joan would have recognised or used to describe their lifestyle, as less than two years before his death, he and Joan were living in a caravan near his farmhouse. They could not live together in the farmhouse itself, as Joan had been in hospital after a serious fall, and social services did not think the conditions in the farmhouse were appropriate for her to live in after discharge from hospital.

As the published judgment of the High Court in Thompson v. Ragget [2018] EWHC 688 (Ch) explains, Wynford, who suffered from prostate cancer, made his last will about six weeks before he died in early 2017, and at the same time wrote a letter in which he said that he did not wish Joan or her children to inherit from his estate. Parts of that letter were quoted by the judge in the published judgment in the case, at paras 2-3:

“In my Will I have specifically made no provision for my partner, Joan Thompson and her children, Gary, Lee, Dean and Sharon. I currently have no contact with Joan’s children. I have no issue with Gary, but I have concerns regarding Lee, Dean and Sharon and do not trust them. I feel that they have previously taken advantage of me and have already received/taken monies from me during my lifetime. I do not want Joan or her children to inherit from my estate.

…

I no longer want to leave my residuary estate on trust to pay the income to Joan for her life as this would be a substantial sum and I do not believe she will need it. Also due to Joan’s health I believe she would not be able to live in my property independently. I am Joan’s main carer and envisage she may have to go in to a home following my death. I confirm Joan has her own finances and is financially comfortable. Joan has her own money and her own savings.”

In fact he was wrong about Joan’s financial circumstances. She had very modest savings, and was otherwise dependent on non-means tested benefits. Wynford had also changed his mind many times about what should be in his last will. Not all of the wills he had made are described in full in the judgment, but the judge said that there were “about 11 wills over the years”, including three in 2012. In some of his earlier wills he had made provision for Joan, but in his last will, he left his estate to a couple who were tenants of one of his properties, and who had given him a little unpaid help at times.

Joan, who was 79 at the date of the trial, had been part of Wynford’s life since the mid-1970s, and had been financially dependent on him all of the time that they had lived together. She had also worked on his farm and in his caravan business without pay, and had helped care for his elderly mother before her death. Towards the end of Wynford’s life she had her own health problems and had spent time in hospital and in a local nursing home, to which she returned after his death. But her GP supported her case that she was well enough to live independently with appropriate social care (which one of her sons and his wife were willing and able to provide), and that it would be better for her to retain her independence than become institutionalised. She was also well enough to attend court and give evidence in which she “answered questions appropriately”.

The judge ordered that Joan should have an outright transfer of a cottage valued at £225,000, which Wynford had bought with a view to them living together there, and a sum of money to cover the costs of adapting and maintaining the cottage and Joan’s moving in and future care from her son and daughter-in-law. As the judge said, this still left Wynford’s chosen beneficiaries “with by far the major part of a substantial estate”. He concluded, at para 48, that:

“Whilst the wishes of Mr Hodge that Mrs Thompson’s family should not benefit from any provision for her should be given appropriate weight, those wishes should not hinder the reasonable provision for her maintenance. That is the mistake that he made in his letters of wishes which led to no provision at all being made.”

The Daily Mail’s explanation for the judge “effectively rewriting” Wynford’s will “in an extremely rare decision” was that he had “failed to match up to his responsibilities to his long-term partner”, and it described Joan as having been “saved from poverty”. The headline and the article all give the judge the air of a benevolent magician, who, in a reversal of the usual role of a magician in a fairytale, makes someone’s wishes (those of the deceased) come untrue. What the story does not say is that Joan had a right created by statute to ask the court to make reasonable financial provision for her maintenance, on the basis that the will failed to do so. She had this right, under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975, not only because she had lived with Wynford for 42 years, but because she was financially dependent on him throughout that time and at his death.

There does not seem to have been any dispute at the trial about Joan’s eligibility to claim as someone who had lived with and been dependent on Wynford, and in the course of the trial the beneficiaries of the estate conceded that his will did not make reasonable provision for her. The only question for the judge to decide was what shape and form reasonable provision should take, and there were a wide range of legitimate possible answers to this question. The striking imbalance between the responsibilities that Wynford had towards Joan as her partner and her carer in ill-health, and towards the two tenants to whom he left his estate, was one factor which influenced the judge in making the decision that he did, and Joan’s limited financial resources were another important factor.

But far from being “an extremely rare decision”, many applications for orders under the Inheritance Act 1975 are made to court every year, although only a minority reach trial without a negotiated compromise. 158 claims were issued in the Chancery Division of the High Court in London in 2016, and there will have been many more in regional district registries and in the Family Division and in the county courts. In December 2011, the Law Commission estimated that over 1,000 claims had been commenced over the past 3 years. The only aspect of the decision that could be said to be “rare” or particularly noteworthy from a legal point of view, is that Joan should have her cottage outright, rather than being granted the right to live in it for the rest of her life, or to have the income from it if she did not live there. This, and other legal points in the case, are more thoroughly and expertly discussed by barrister Charlotte John in her “Equity’s Darling” blog.

The Inheritance Act 1975 is such an important part of the law of inheritance that it seems a striking omission not to say anything at all, even in a popular newspaper article, about its existence, and the rights that it gives cohabitants to make claims for reasonable financial provision under it. The law has existed in some shape or form since 1938, although it has only applied to cohabitants since 1995, and its existence means that it is not true to say, as many people believe, that, in England and Wales, provided that you have mental capacity, exercise your own free will, and comply with the formalities for making a valid will, you have the right to make a will leaving your estate to whomever you wish. Rather than being an unwelcome encroachment on absolute freedom of testation, the Inheritance Act surely reflects a civilised view of what a legal system should do to protect people from the neglect, capriciousness or mistaken beliefs of those who owe them obligations arising out of kinship and/or financial dependency. Nor does the Inheritance Act operate in an arbitrary “magic wand” fashion, but, as the Law Commission described it in its 2011 report:

“It is not a matter of the court making an order that is, in some general sense, fair in the circumstances; nor can the court respond to what an individual deserves, nor to what the deceased ought to have or might be supposed to have intended to have done . . . the court can make an order only if it satisfied that the disposition of the deceased’s estate effected by his will or the law relating to intestacy, or the combination of his will and that law, is not such as to make reasonable financial provision for the applicant.”

The need for a wider and better public understanding of the existence of the Inheritance Act 1975 and the powers of judges making decisions about it, is painfully underlined by some of the 1,000+ comments on the Daily Mail’s article, in a full-flowing vein of tabloid “o tempora, o mores”, such as

“This country is getting worse and now we have the courts being able to disrespect the wishes of the dead”

There’s a particular irony to this comment, as only a few months ago, in another case which was prominently covered by the Daily Mail, the High Court ordered that the wishes of the notorious murderer, Ian Brady, about his own funeral ceremony, should be disregarded in the public interest. I have written in more detail about this decision here.