Bad Faith Bunnies – A bitter/sweet Easter Tale

Weekly Notes, the ICLR roundup of recent legal news and commentary, is currently on holiday. We’ll resume publication in the next law term, which begins on Tuesday, 25th April. In the meantime, here’s an Easter-flavoured tale from the archives of the Business Law Reports (Bus LR). It’s all about that most festive of confections, the chocolate… Continue reading

Weekly Notes, the ICLR roundup of recent legal news and commentary, is currently on holiday. We’ll resume publication in the next law term, which begins on Tuesday, 25th April. In the meantime, here’s an Easter-flavoured tale from the archives of the Business Law Reports (Bus LR).

It’s all about that most festive of confections, the chocolate bunny.

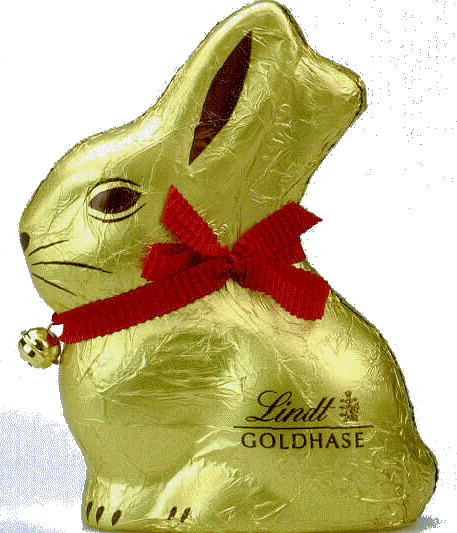

Bitter rivalry between Swiss-based Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli AG (the claimant) and Austrian chocolatiers Franz Hauswirth GmbH (the defendant) led to a judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Communities (ECJ) in Case C-529/07, ECLI:EU:C:2009:361, [2010] Bus LR 443, containing (at paras 12 and 14) sweet little pictures of their rival gold-wrapped red-ribboned rabbits (above).

Spot the difference, if you can. Because that was the substantive issue: just how different, or confusingly similar, they were. And if so, whether one of them was infringing the other’s trade mark.

Using suitably technical words like ‘oviparous’ and ‘lagomorph’, Advocate General Eleanor Sharpston QC explains the background to the dispute in her Opinion, ECLI:EU:C:2009:148, at para 22:

Part of the mythology of Easter is an egg-bearing creature known as the Easter bunny. (Different languages categorise the creature as a hare or a rabbit, and the English “bunny” is perhaps flexible enough to encompass both. In Australia, where rabbits are viewed with disfavour, its mythological niche has been partly taken over by the “Easter bilby” (although, given the animal’s possibly oviparous nature, one might have expected an “Easter platypus”). The article sold under the trade mark in issue in the present case is termed by its manufacturer “Goldhase” in German, “Gold bunny” in English, “Lapin d’or” in French, “Coniglio d’oro” in Italian, etc. Fortunately, the exact zoological classification of this (probable) lagomorph is entirely irrelevant to any of the issues in the case. For many decades, chocolate makers in at least the German-speaking areas of Europe have produced and sold chocolate bunnies at Easter time, in various shapes and with wrappings of various kinds and colours but often largely of gold-coloured foil, and often decorated with a ribbon and/or bell. Since the introduction in particular of machine wrapping in the 1990s, technical constraints have caused the shapes of those chocolate bunnies to become increasingly similar. (The selection displayed at the hearing suggests that there are two basic forms which meet those technical constraints, with the animal sitting in either a crouching or an upright position.)”

The battle of the bunnies

Lindt, who had produced Easter bunnies since the 1950s and marketed them in Austria since 1994, applied in 2000 for registration as a Community trade mark of a three-dimensional sign representing an Easter bunny, which had already acquired a certain reputation with the public, and the sign was duly registered in 2001. They then accused Hauswirth, who had produced and marketed similar chocolate Easter bunnies since 1962, of trade mark infringement, on the ground of “likelihood of confusion”.

Hauswirth counterclaimed that the claimant’s mark should be declared invalid, on the ground that, at the time of filing the application for registration of the mark, the claimant had been “acting in bad faith” within the meaning of article 51(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 on the Community trade mark.

The reference to Luxembourg

The Austrian court, having found that Lindt was aware that other manufacturers had been producing chocolate bunnies similar to its own since the 1930s, and that at least some of those manufacturers had acquired certain rights to their presentations (even though none of them had actually been registered), sought clarification from the ECJ on the circumstances in which, in such a case, an applicant was to be regarded as having acted in bad faith.

The ECJ duly obliged, saying that the national court had to take into consideration all the relevant factors specific to the particular case which pertained at the time of filing the application for registration of the sign as a Community trade mark, and in particular (i) the fact that the applicant knew or must have known that a third party was using, in at least one EC member state, an identical or similar sign for an identical or similar product capable of being confused with the sign for which registration was sought; (ii) the applicant’s intention to prevent that third party from continuing to use such a sign; and (iii) the degree of legal protection enjoyed by the third party’s sign and by the sign for which registration was sought.

In other words, the fact that Lindt knew that Hauswirth (and others) were already using a similar sign or design in the same market could indeed infect their application for trade mark registration with bad faith. On the other hand, it might not. The matter was one for the national court to decide.

The Austrian conclusion

As it happened, when the case went back to the Austrian courts, according to the IP Kat blog, they ended up supporting Lindt’s claim and rejecting Hauswirth’s counterclaim. The Commercial Court of Vienna decided that Hauswirth should no longer be allowed to sell chocolate bunnies that were confusingly similar to Lindt’s (original and now registered) bunnies.

Hauswirth appealed that decision but the Austrian Supreme Court in April 2012 confirmed the Commercial Court’s decision, handing Lindt the Easter gift of their lawyers’ dreams. In fact Lindt were quoted as saying they “were not out to destroy Hauswirth but did not wish to see plagiarised bunnies”.

No, of course not. Hauswirth can hop it. And Lindt’s chokky bunnies now have a tinkly little gold bell on them, too. Vorsprung durch glocken!