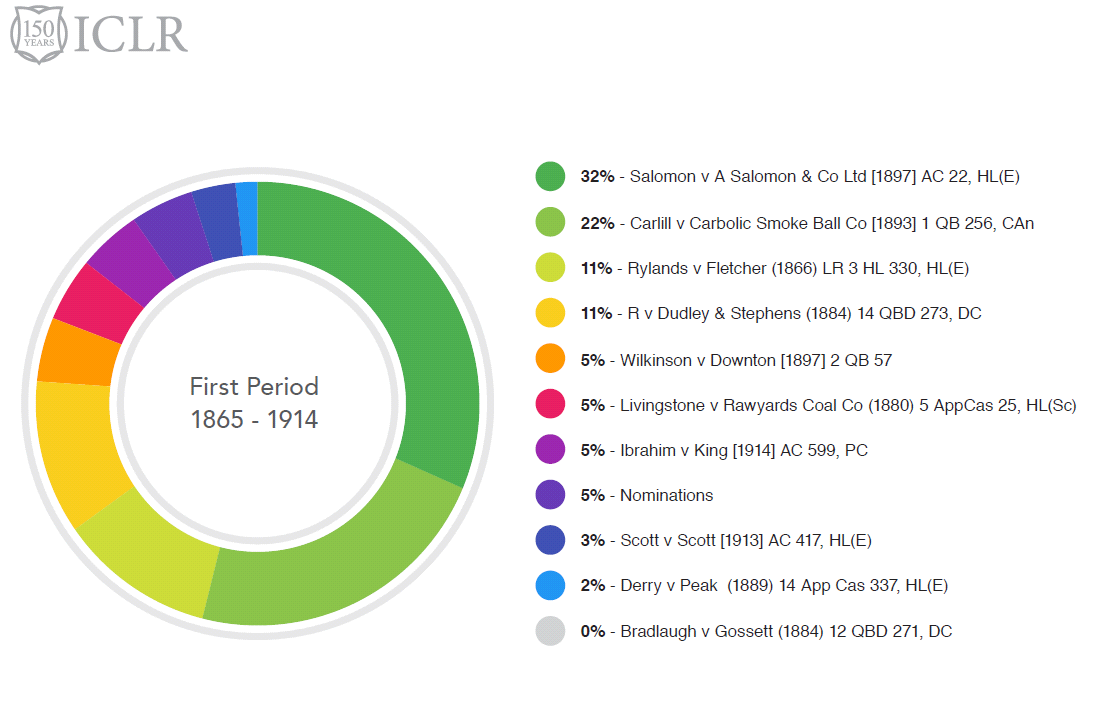

Case Law On Trial – the results: 1865 – 1914

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period.… Continue reading

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period. In this post, we look at the results from the first period, 1865 – 1914.

As this graphic shows, the choice of the top three cases from our first voting period were fairly conclusive. The three winning cases will be included in the special Anniversary Edition, to be published next month to mark our sesquicentenary, or 150th anniversary. In this post we say a little more about the cases that were chosen for this period.

No one could dispute their significance to the long term development, or study, of the law. The only major disappointment was the omission of the case fourth place – R v Dudley & Stephens (1994) 14 QBD 273. While we were conducting the online vote, in February 2015, it was running neck and neck with Rylands v Fletcher (1866) LR 3 HL 330: see our update on the voting at the time. But for all its fame as “the case about the shipwrecked cabin boy” (who was eaten out of necessity – not a defence which his cannibal sea-mates could rely on against a charge of murder), it failed to match the popularity of the one which asks “who, in law, floods his neighbour?” or words to that effect.

1. Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22, HL(E)

The idea of a corporation as a separate legal person was nothing new when this case was decided. It had been provided for in the Companies Act 1862, along with the limited liability which such a personification enjoyed. What makes this case memorable is perhaps the audacity of Mr Aron Salomon (described in the title as a “pauper”) in setting up a company that was essentially a one-man band, his wife and children being the only other shareholders. The judge (Vaughan Williams J) and the Court of Appeal evidently thought the whole thing a bit of a scam, or at any rate “scheme”, contrary to the meaning and true intent of the 1862 Act, and refused to countenance it: see Broderip v Salomon [1895] 2 Ch 323. But the House of Lords declared it to have been, at its inception, a perfectly reasonable business venture, within the terms of the 1862 Act. Nowhere in any the judgments of the three courts, or the argument recorded before them, can the expression “veil of incorporation” (or “corporate veil”) be found, but that is the phrase now used to describe that which may only be “pierced” in certain limited circumstances, between a company and its members or directors. The terminology has echoes of certain kinds of conjugal ritual which I think it would be improper to explore in too much detail here, but it seems apt that the most recent major case to consider whether to disregard the separate personality of a company arose in the context of a divorced wife seeking to attribute to her husband assets held by offshore companies owned by him. This was permitted by the judge, but refused by the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court which, however, found a different way out of the maze – by ordering the companies themselves to disgorge the properties, which it inferred to be held on trust for the husband, and to transfer them directly to the wife: see Prest v Prest [2013] UKSC 34; [2013] 2 AC 415, SC(E). In this way the sacred veil of incorporation was preserved unpierced.

2. Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co [1893] 1 QB 256, CA

Next in time, we have a case the facts of which are reminiscent of snake oil salesmanship in its wild western prime. These days the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company would be being sued (in a billion-dollar class action) for failing to include a health warning on the packet; but in that late Victorian era the issue was one of the manufacturer not coughing up enough rather than the consumer doing so too much. If Hawkins J at first instance knew that what he was really dealing with was a case about the formation of a contract, the law reporter in drafting the catchwords seems to have thought it was principally about gaming and whether the advertisement was some kind of bet: [1892] 2 QB 484. Although Hawkins J did deal with the gaming and insurance issues raised by counsel, his decision, as affirmed by the Court of Appeal [1893] 1 QB 256, rests on a question of contract, as the catchwords to the latter report (reproduced here) make clear. Indeed, the judgment of Lindley LJ more or less dismisses the gaming and insurance aspects of the case as hopeless (counsel no doubt making the best of the bad hand dealt to him) before rather drily scorning the idea that the advertisement for the eponymous fumigaceous remedy might have been a mere “puff”. Lindley LJ’s involvement in such a significant case is interesting given his role in the original formation of the Council of Law Reporting (see A History of The ICLR, ante, p ??). The case was a popular choice for the present volume not least because it is certainly one of the most memorable of the cases one has to learn as a student. So memorable, in fact, that it has spawned a range of quasi-legal and office-related memorabilia, such as mugs bearing the legend “Lean mean billing machine”, cufflinks saying “Guilty” / “Not guilty” or “Old lawyers never die”/ “They just lose their appeal”, and copies of the original “£100 Reward” poster to adorn your firm’s or chambers’ waiting room along with all those leatherbound law reports. You can find it online at www.carbolicsmokeball.com Explaining the company’s choice of name to a less specialised customer base, the website reflects indirectly the global commercial appeal of the common law:

“Our first range of products was designed exclusively for lawyers, so when we were looking for a name back in the 1990s, it seemed logical to choose one that would mean something to them. Though quaint and old-fashioned, ‘Carbolic Smoke Ball Co’ had a ring to it, and we knew it would be recognisable to lawyers in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Pakistan, South Africa, the USA and many other parts of the world. Of course, it is incomprehensible to non-lawyers who, for the most part, assume we make soap.”

Soft soap, perhaps, but hard sell.

3. Rylands v Fletcher (1868) LR 3 HL 330, HL(E)

For a case to have created a new cause of action is rare, and for it to have lent its name to that cause of action is even rarer. Rylands v Fletcher is perhaps the prime example. Although the headnote refers to both trespass and negligence (on which the case was initially argued), the cause of action it created seems so specific that it has its own entry as a subject matter heading in that standard work of reference, the Consolidated Index to Leading Case Reports. In the Exchequer Chamber, reversing the decision of the Court of Exchequer, Blackburn J delivering the reserved judgment of the court identified the principle as follows, LR 1 Exch 265, 279:

We think that the true rule of law is, that the person who for his own purposes brings on his lands and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief if it escapes, must keep it in at his peril, and, if he does not do so, is primâ facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of its escape.

The Exchequer Chamber based its judgment on previous authorities involving the escape of cattle and other animals, causing damage on a neighbour’s land, and cases involving drainage and mines. The judgment cites authorities dating back to the Year Books. Why, then, does the case seem so unique? Yet, as recently as Gore v Stannard (trading as Wyvern Tyres) [2012] EWCA Civ 1248; [2014] QB 1, CA, the “rule in Rylands v Fletcher” was being applied as a discrete cause of action, albeit the facts were distinguishable. The rule is now considered and applied by reference to the judgment of the House of Lords included herein, in which Lord Cairns LC both approves the judgment delivered by Blackburn J in the court below and adds his own spin: the idea of a “non-natural use” of land, imposing on the owner a duty to ensure such use does not give rise to an escape of something mischievous, or at any rate a duty to compensate where it does. In short, such a non-natural use must be “at [the owner’s] own peril”. The rule is one of strict liability. Lord Cranworth, concurring, expressly disavows negligence as an element in the cause of action, at p 341: “the question in general is not whether the defendant has acted with due care and caution”. And in one of the authorities he cites (at pp 341-341), Baird v Williamson (1863) 15 CB (NS) 376, the owner of a mine was held liable for an escape of pumped water into a neighbouring mine even though it was “done without negligence”. The rule in Rylands v Fletcher was itself viewed as a dangerous precedent whose escape into other jurisdictions might cause damage to the law there applicable: in “Between Speech and Writing”, one of the essays in the Anniversary Edition, Professor Paul Mitchell alludes to the fact that the Privy Council created a public interest exception to the rule in Madras Railway Co v Zemindar of Carvatenagarum (1874) LR 1 Ind App 364, which he has elsewhere explained as a deliberate attempt by the Privy Council, as a colonial court of final appeal, to adapt the common law to the different local conditions of a specific jurisidiction (see Mitchell, “The Privy Council and the Difficulty of Distance”, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies (2015), pp 1, 26-28).

We’ll continue to explore the cases voted for by you, the readers, in further posts in this category (Historic Cases) on the ICLR blog over the next month or so. And you can read the judgments and PDFs of the original law reports of all the shortlisted historic cases on BAILII here.

> Back to 150 Years of Case Law on Trial